125 Years of Utah and the Movies — Part One: The Mormon Exploitation Film

The first installment of a year-long series celebrating and rediscovering 125 years of Utah onscreen.

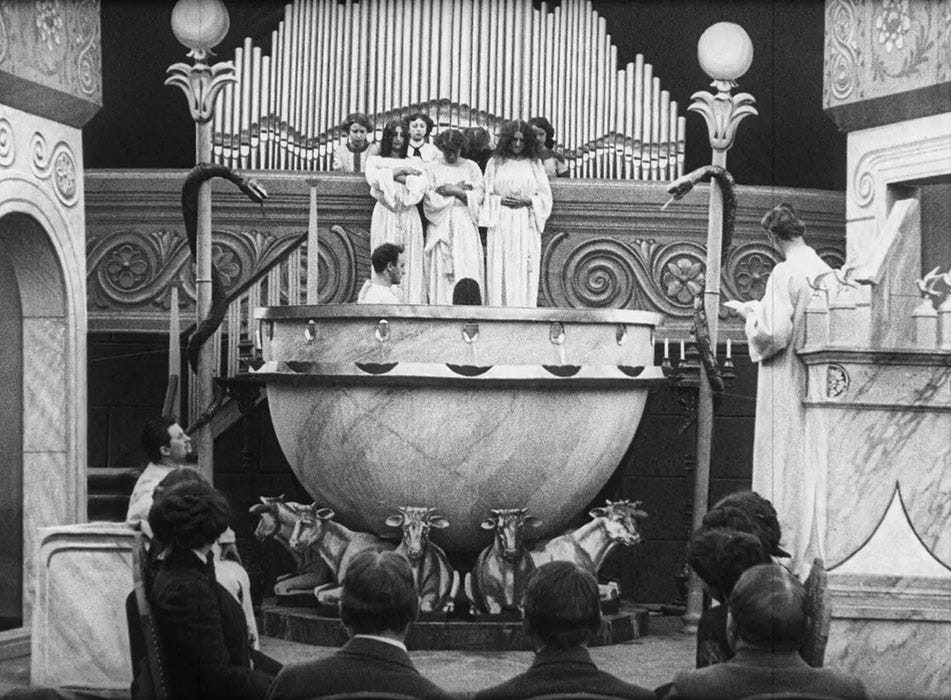

A still from the 1911 Danish feature film A Victim of the Mormons.

Within the past month, both the state of Utah and the medium of film turned 125 years old. On December 28, 1895, the inventors and photographers Louis and Auguste Lumiere ushered in the now ubiquitous art of projected film to a small, paying audience in the basement of the Grand Café in Lyons, France. One week later and an ocean away, President Grover Cleveland officially welcomed Utah as the 45th state of the United States of America on January 4, 1896.

Over the past 125 years, Utah has played an active role in film history, providing Hollywood films with some of its most breathtaking landscapes, harboring a creative independent film industry and culture, and giving birth to various famous and talented filmmakers. Film, in turn, has similarly played an active role in Utah’s history, providing jobs and entertainment to millions of Utahns while helping shape the state’s image worldwide.

To celebrate these monumental anniversaries of history, throughout the year I will be looking back on Utah and film’s ever-evolving relationship and history. Part One in this series explores Utah’s relationship with early cinema and Utah’s religious and secular leaders’ fight against negative depictions of Mormons in early 20th century films.

The Beginnings of Cinema in Utah

Long before the arrival of cinema to the state, the majority Latter-day Saint Utah population was frequently engaged with and creators of popular 19th-century entertainment. To give a permanent home to several productions of theatrical plays that had dated back to the Saints’ time in Nauvoo, Brigham Young personally advocated for constructing the Salt Lake Theater in the early 1860s, despite the time, labor, and resources it took away from the city’s temple. While many 19th century Christians looked down on or remained skeptical of the theater, several Latter-day Saint leaders encouraged, supported, and sometimes even participated in theatrical productions on the condition that it provided clean, wholesome entertainment in line with the current church standards.

For example, apostle and Salt Lake City mayor Daniel H. Wells in 1883 taught that “Latter-day Saints can pass their time pleasantly in enjoyment of every kind, so long as they will do without sin” adding a warning that “the adversary... sometimes perverts these things [theater]” (Journal of Discourses, 24:314). Wells’ belief in the potential and corruptibility of entertainment would prove to be prescient as the church and its standards lost influence over what could and should be portrayed on stage, and later the screen, amidst the late 19th-century migration of thousands of non-Mormons to Utah. This double-sided enthusiasm for and fear of late 19th and early 20th-century entertainment would be the foundation for the Church’s and its members’ beliefs and attitudes towards the emerging medium of film’s arrival in the newly minted state of Utah.

Because of the nature of early film exhibition strategies, it is hard to definitely declare when and where the first screening in the new state of Utah took place. Before the 1905 explosion of storefront Nickelodeon theaters throughout the United States, films were most predominantly shown in vaudeville and opera houses, by traveling educational lecturers, and at special events such as state and county fairs. For example, the local Lyceum Theater, predominantly dedicated to live vaudeville performances, added a “new series of moving pictures and illustrated songs” to their weekly Sunday concerts series (Ogden Standard-Examiner, 16 November 1903, page 6). Most Utahns would have first encountered projected films not in a movie theater as we are accustomed to today but in a more traditional 19th-century entertainment venue such as in a vaudeville hall.

As film slowly entered Utah entertainment venues in the late 1890s and early 1900s, Utahns began to be shown on the silver screen. The first known instance of Utahns being photographed is in a nearly two-minute actuality film entitled Salt Lake City Company of Rocky Mountain Riders (1898). The American Mutoscope Company, which would later become the famed Biograph Company, filmed a group of Utah soldiers in training at Jacksonville, Florida during the height of the Spanish-American War. While this short film (now presumed lost) showed Utahns as dutiful, loyal countrymen, future depictions of the state would solely center on its Mormon inhabitants, mirroring the negative depictions of Mormons in 19th literature and media.

One such early film depiction of Mormons was 1905’s A Trip to Salt Lake City. Taking place in a railway car, the film shows the trouble a polygamist has taking care of all of his wives and children. Played for comedy, the husband is bombarded by his wives and children who need help going to bed. Whether it is playing with his many young children or getting water for his harem, the Mormon polygamist’s troubles are something to laugh at. While being the punchline in several comedy films may have been displeasing, before 1910 Mormon representation in films remained insignificant enough that it received little attention from church members or other Utahns; however, starting in 1911, the dozens of films with negative depictions of Mormons would enthrall the church and state in a fight to control their own portrayal in motion pictures around the world.

Information originally published in A History of Latter-Day Saint Screen Portrayals: The Anti Mormon Film Era 1905-1936, 259-260.

The Mormon Exploitation Film

When a flurry of films centered on negative depictions of Mormons flooded the screen in 1911, cinema had fully transformed from a small, side industry to become a full-fledged international production, exhibition, and distribution network. The short one to ten minutes films of the 1900s grew to become full-scale, hour-long plus productions by the early 1910s. European films in pre-World War I America were almost two-thirds of the films released in the country’s market just as film companies slowly migrated from New York and New Jersey to the small town of Hollywood, California.

When A Victim of the Mormons, one of the earliest and most influential films depicting Mormons, debuted on Danish screens in 1911, the film’s production company Nordisk was the world’s second-largest film production company, widely respected for the quality and dramatic essence of their films. Setting the record for the longest Danish film upon its release at over forty-five minutes, A Victim of the Mormons was primed to do big business in both the domestic and international markets. Its early success in Denmark and Great Britain and later release across the United States would not only spark the production of numerous other Mormon-centered films but also bring Utahns, both Mormons and non-Mormons, together in a fight to control their own depictions on the silver screen.

In the film, Florence, a young Danish woman, runs away with the Mormon priest Andrew Larson after feeling neglected by her boyfriend. After having second thoughts once aboard a ship out of Denmark, Larson forces Florence to travel to Utah against her will. Florence’s family and boyfriend travel to Utah to save Florence from the grasp of the villainous Larson, ultimately leading to a frantic car chase through the streets of Salt Lake City.

While A Victim of the Mormons in large part created the subgenre of Mormon exploitation, it more closely aligns with the tropes and story of previously popular Danish films centered on scandalous accounts of human trafficking than subsequent Mormon depictions. Danish film companies Fotoroma and Nordisk previously had sought to exploit the public’s fears associated with sensationalized headline stories of white women being kidnapped into sex slavery to create intrigue, sell tickets, and rake in substantial profits. Nordisk’s 1910 international success The White Slave Trade (think an early 20th century Taken) tantalized audiences by showing the inside of a brothel and a daring rescue of a Danish woman held in sex slavery in London. In essence, A Victim of the Mormons is a subgenre of a human trafficking exploitation picture, using the exoticism and mistrust of Mormon missionaries in Denmark and Europe instead of human traffickers to shock its audience and fill theater seats.

A still from A Victim of the Mormons (1911) depicting the inside of the Salt Lake Temple.

Because of its association with the sex trade genre, A Victim of the Mormons’ portrayal of Mormons is much less inflammatory than many subsequent negative depictions of Mormons. While Larson is the villain of the film, his actions are not sanctioned by church leaders or connected to the church’s doctrine of polygamy. Larson is similar in age to Florence, not a predatory elder looking to add another young wife to his already growing harem. While a scene depicts an overdramatic, cult-like temple baptism in Salt Lake City, a Danish Latter-day Saint congregation is depicted in a rather straightforward manner devoid of negative stereotypes. Mormons are clearly portrayed as untrustworthy outsiders; yet, the film leaves much of its interpretation to the audience, refraining from portraying all Mormons in a negative light or labeling Larson’s sins as evidence of Mormonism’s systematic flaws or historical misdeeds.

A more stereotypical example of subsequent Mormon exploitation films is 1917’s A Mormon Maid, released by Paramount and produced by Cecil B. DeMille. In the Old West, a non-Mormon, frontier couple and their teenage daughter are accepted into a Mormon community after their cabin is destroyed by a local Native American tribe. After a couple of years living among the Mormon settlement, the father is forced by the church elders to either enter into a second marriage or give his daughter away to one of the older church elders. With the help of a friendly young Mormon suitor whom the film describes as being “wholly ignorant of the ugly of early Mormonism”, the father and daughter escape from the Danite elders of the church and start a new life on the frontier outside of the Mormons’ grasp.

The Danites oversee a forced polyandrous wedding in A Mormon Maid (1917).

Unlike A Victim of the Mormons, A Mormon Maid portrays Mormons as a cult centered on polygamy and male power, unwilling to co-exist with any non-Mormons. The film borrowed the historically inaccurate trope of vigilante Danites from 19th-century literature, even claiming that white robes worn by the Danites inspired the garb of the Ku Klux Klan. Brigham Young, simply named “The Lion of the Lord” in the film, presides at the head of the group of white-hooded figures tasked with stamping out any opposition or non-Mormons.

While many Mormon scholars have defined these films as anti-Mormon, the term Mormon exploitation better captures the various sensationalized depictions of Mormons in these films. While some exhibitors advertised the film as an expose of the Mormons, these films weren’t made to debunk Mormon claims or dissuade its viewers from converting to the church but to profit off an already sensationalized topic. Rudger Clawson, the president of the church’s European Mission during the release of A Victim of the Mormons, predicted that “these disreputable shows will go as long as the almighty dollar goes with them, but when the dollar fails to show up the pictures will sink unto oblivion” (Journal of Mormon History, Vol 29, No. 2, 50). Even if the producers and distributions of Mormon exploitation films sought only to capitalize off anti-Mormon sentiment to make a wealthy profit, these films threatened the church’s conversion efforts worldwide and damaged the young state’s reputation in the United States and abroad.

The Reaction of Church and State

While the church had previously faced the negative depictions of Mormons in dime novels and plays in the 19th century, the increased exposure of early 20th-century motion pictures made it harder for the church to adequately defend itself against the negative depictions released on screens across Europe and the United States. Missionaries first countered these films in Great Britain and Denmark by passing out tracts at screenings of A Victim of the Mormons in late 1911. One such tract offered two hundred pounds to anyone who could produce evidence that a missionary had kidnapped British women and taken them to Utah. While the tracts handed out by European missionaries sought to give moviegoers the church’s vision of themselves, these efforts did little to dissuade theater owners to pull these films off their screens.

A more concerted and multi-faceted effort was undertaken by church and state leaders when these Mormon exploitation films hit American screens in early 1912. In reaction to Pathé Frères’ 1912 film The Mountain Meadows Massacre, a variety of theater owners, church members, businessmen, politicians, and local organizations appealed to Pathé and local film distributors. For instance, the predominantly non-Mormon Salt Lake Commerical Club telegrammed Pathé directly, declaring The Mountain Meadows Massacre a libel on the state of Utah and demanding the film company to withdraw the film from circulation. Utah governor William Spry promised, “to do all in his power to prevent any of Pathe’s films [the world’s largest film production company at the time] from being screened in Utah if it decline cooperation”. (Journal of Mormon History, Vol. 29, No. 2, 54)

Church leaders primarily focused on persuading the National Board of Censorship, an east coast censorship board that reviewed films for objectionable content, to revoke its previous approval of A Victim of the Mormons and to publicly condemn the picture. The church sought help from various parties in this effort to censor A Victim of the Mormons including apostle and Utah senator Reed Smoot, the Eastern States mission president Ben E. Rich, and non-Mormon independent film producer William H. Swanson. Smoot gained co-operation with several other western congressmen, Rich directly lobbied the National Board of Censorship, and Swanson published a plea in the popular magazine The Motion Picture World for the film industry to denounce the unfair and negative depictions of Mormons onscreen (“The Sectarian Film Once More”, Moving Picture World, 282).

These campaigns carried out by businessmen, politicians, and church leaders successfully persuaded the National Board of Censorship to rescind its official approval of the film; however, this condemnation did little to stop these Mormon exploitation films from being distributed across the United States. Nordisk’s American distributor The Great Northern Film Company released A Victim of the Mormons without the National Board of Censorships’ approval, using the church’s fight against the film as a means of advertising with great success. Although Utahns’ efforts to suppress these films did little to stop the inflammatory onscreen Mormon representations from gaining widespread distribution, Mormon exploitation films would never again reach the success, frequency, or popularity that they enjoyed in 1911 and 1912.

Based on the popular Western novel by Zane Grey, Riders of the Purple Sage (1918) features a skirmish between Mormon and non-Mormon cattle rustlers in the fictional town of Cottonwood, Utah (Moving Picture World, 21 Sep 1918, 1537).

Subsequent Mormon exploitation films faced more pushback in the United States after 1912. In 1917, the National Board of Censorship required A Mormon Maid to include a disclaimer stating that the film’s fictionalized events and characters didn’t represent current Mormon behavior or beliefs. Shortly after Fox re-released their 1918 western Riders of the Purple Sage in 1921, a complaint from Senator Smoot persuaded Fox to pull the picture from distribution and promised to never screen it for the public again. When Fox remade Riders of the Purple Sage in 1925, they recast the book’s central villainous Mormon bishop as a secular judge and sought personal approval from Senator Smoot before releasing the film. When the popular British 1922 film Trapped by the Mormons entered Canadian theaters, church and state leaders were able to successfully prevent the film from receiving an American release.

Even though the decline of Mormon exploitation films in the silent era was due more to the lack of interest of 1920s audience members than the church’s efforts to suppress and censure these films, the efforts of Mormons and non-Mormons alike had a lasting impact on both Utah’s image onscreen and internal state politics. The coalition of both Mormon and non-Mormon individuals and groups showed that despite tensions between the two factions in state politics, co-operation could be achieved on issues that hurt the state’s image and economical potential.

Perhaps even more impactful than building bonds between the religious and secular Utah communities was the church’s and state’s discovery of the power of motion pictures. When denouncing A Victim of Mormons in his April 1912 General Conference address, then apostle David O. McKay declared that the motion picture was “a stronger means of disseminating knowledge, even than the press…when you may sit and see it acted, see it portrayed as naturally as though it were being enacted in the every-day life, then the mental pictures are given as definitely and as rapidly as the motions of the actors can portray them” (82nd Annual Conference Report, 53). In the first two decades of film, church leaders like Elder McKay and many non-Mormon Utahns had seen the persuasive power of film used to denigrate and attack both the church’s and state’s image. Following the losing fight over censoring negative depictions of Mormons and Utah in 1912, both the church and non-member Utahns would begin to play an active role in creating films to portray their state and religion in a more realistic and positive light.

______________________________________________________________________

Part Two of the series covers the beginnings of Utah’s independent filmmaking production.

This is an incredibly interesting article. It's fascinating to see how Utahns used their political power, though limited, to push back on these "Mormon Exploitation" films.