Recently, the Utah Monthly had the chance to sit down with Kerry Soper, a professor in BYU’s Department of Comparative Arts and Letters and an accomplished landscape painter, to discuss his art and his involvement with Spring City’s annual Heritage Day festival. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Could you talk about your artistic background?

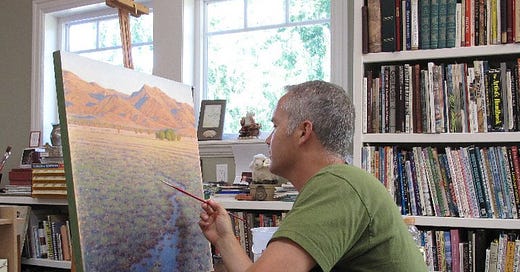

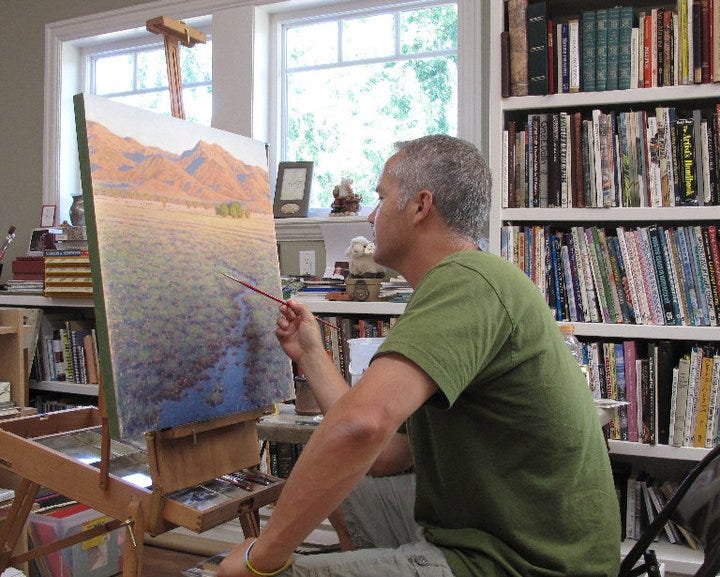

I studied art at Snow College and Utah State. And for a time, I wanted to be a commercial artist, because I was scared about how difficult it would be to make a living as a fine artist. After a failed internship at a design studio, I decided commercial art wasn’t for me, and found my way into academia, studying comic strips and the history of popular art. But I always, in the back of my mind, aspired to be an artist at some point in my life. And I think because of my experience living in Spring City, during two different periods of my life, I gravitated back to fine art. While there, I got exposed to an art community and a set of art teachers, who were landscape painters and who were really tuned in to not just the monetary benefits of being a successful landscape painter, but the deeper spiritual and philosophical reasons for pursuing that as a craft: As a way of communing with heritage, and with the beauty of green spaces in a way that a lot of people could benefit from, as an artist and your own mental health, but also collectors that would want to hang these paintings in their home.

And I see myself joining a tradition of Utah artists and American artists—realists or naturalists—who want to celebrate the beauties of humble rural locales, like the intersection of wilderness and human-shaped, rural landscapes. The way we try to create these geometric gardens of fields and gardens and homes, little Mormon communities where you’re turning arid environments into these cultivated gardens and landscapes that have a stark beauty to them. So in the distance, you still see those arid hills and that kind of deep landscape setting or history, but in the foreground, you see, almost in geometric forms, outbuildings, and fences and cultivated fields and gardens. And so it’s a fun way to meditate on humans trying to curate and shape and garden a landscape in ways that are both beautiful and beneficial in terms of growing food. That’s the subject matter that I really like. I’ve tried to explore that in France and England as well—the stone fences and the sort of checkerboard fields that also emphasize that intersection of natural landscapes with agrarian kinds of endeavors. Artists that I aspire to be like would be Maynard Dixon, George Inness or Winslow Homer, artists who also took on some of the same subjects. I'm not trying to be too avant-garde, I’m trying to step into a late-nineteenth century tradition of sensitive treatments of every day, realistic American rural sites. Not too romantic. Michael Workman, Doug Fryer, these guys are actually Spring City painters that I have rubbed shoulders with. I even did a little bit of an apprenticeship with Michael Workman when I was just out of grad school, and I've benefited from learning about some of his methods and philosophy. Gary Ernest Smith, he's another Utah artist, LeConte Stewart—there’s a little bit of a legacy of this kind of landscape painting that I’m trying to dip into.

Do you identify more as a Utah artist or an American one?

Utah artist. There’s a theological vision that undergirds some of the paintings, like the scriptures from Isaiah about deserts being transformed, and other passages from the scriptures that talk about God intentionally structuring our environment with rivers and streams and trees to make our existence happier and give us aesthetic pleasure. And so the way an artist can act as a mediator in helping other people to see and appreciate those beauties—you don’t want to embellish too much what is existing there that’s already beautiful, but you do have artistic license to curate and artfully organize the elements so that it makes it a poetic, distilled treatment.

I imagine that painting is not primarily a didactic endeavor for you, but is there any lesson that you’re trying to get across in your work? Any implicit commentary on the ways in which we use or overuse our natural resources?

So many people undervalue the beauties of an arid Utah landscape. They’ll say things like ‘I drove from here to there in Utah, and it was just boring nothingness.’ And they’re accustomed to thinking of lush Eastern landscapes or exaggerated Thomas Kinkade fantasies, with every possible flower blooming, and always an abundance of water and streams, so that makes people disregard the value of where they live. I think they are in denial about what native plants are, and what could count as beautiful. So in my own paintings I’ll show cultivated fields that benefit from irrigation, but I also want to highlight the effort it took to carefully create those systems, and then the fact that surrounding those fields are these arid expanses. And the stark beauties of those scenes. So sometimes I’ll do paintings in southern Utah that try to get people to slow down and think about the fact that that’s not just a site of desolation, but there are incredible things going on with the red rock and the shadows and the intersections of the blues and warmer colors as the sun sets and it’s just abstract in its complexity. Not being too romantic, not denying what’s there in front of us in terms of this beautiful arid place, is part of what I’m trying to celebrate and make more familiar. There are so many interesting blues and yellows and tans and purples, an array of colors that you don’t get in the East, where everything is lush and green. That’s almost boring to my brain in comparison to the complexity of different planes and colors that are introduced because of a desert landscape intersecting with a cultivated landscape.

Could you talk about the history of the Spring City Heritage Day and Art Festival?

One cool thing about this show is that it’s in Spring City, which is a little town in central Utah that kind of got trapped in a late-nineteenth century vibe. The progress that overtakes some cities kind of missed Spring City; people just left the town and it has more standing outbuildings from pioneer times than any town in Utah. So it’s not just the pioneer homes that have been preserved—it’s also sheds and barns and outbuildings. Just a variety of buildings you might use to protect livestock, or chicken coops, just the random little structures. They just never got torn down. And so you’ve got these big acre lots with sprawling outbuildings and old trees, mature trees.

Then in the 1970s, there were local people who stepped up and started to protect the pioneer structures in that town, finding government grants to preserve and restore. And that helped keep that architectural integrity in place. And then it was even elevated to being a National Historic District in 1980. Because of the high concentration of pioneer homes and outbuildings, there was a small crisis, maybe in the mid-1970s, where the Church was going to tear down this beautiful church house from pioneer times built out of this oolite stone, this amber color, beautiful stone, and the town banded together and petitioned the Church to protect and preserve it. And it’s still there; it’s become an icon.

And then, over the past thirty years, there has been a big effort made to preserve this awesome grade school in the center of the town. It’s three stories high and is just massive and Gothic looking, it’s just insane. But because of the established pattern of promoting the historic qualities of the town, and then a growing arts community that was developing in the town, some charity programs and fundraising programs were put into place to help fund the thousands and thousands of dollars it would take to preserve this old schoolhouse. And so one thing that became a tradition was a celebration in May called Heritage Day. And it’s the last Saturday of May, every year, the town opens itself up to a party basically, and has a turkey barbecue dinner in the park. And there's a home tour, which is probably the most popular central activity of that day, where people pay $10, and they can walk through something like twenty old pioneer homes, and just wander the dusty streets and see all the outbuildings and the old trees. It’s such a cool atmosphere, you feel like you’re going back in time. So that’s become bigger and bigger each year. And it is massive, the number of people from Salt Lake and the Wasatch Front who come down to enjoy that day. And a lot of the proceeds go to charity. And so for maybe twenty years, that money was fueled into the restoration of that old school building. They finally achieved their goal, about two years ago, of turning the schoolhouse into a fully refurbished, historic building. The governor came down and there was a big ceremony. And most of that was because of those charity efforts.

But also part of the Heritage Day for all those years, and I’ve been involved with it since maybe 1998, is an art show and an art auction. And it’s called Art Squared since every painting in the auction is a twelve by twelve square. And they’re unframed. They’re all mostly on boards, painted on boards, mostly oil, but you know, other mediums as well. And it’s a really eclectic, democratic show, where you get amateurs and professionals rubbing shoulders, and it’s grown year after year. It’s almost too big for its own good now, we had like 130 paintings last year in the auction. And some really great Utah artists participate, like Lee Bennion, Brian Kershisnik, J. Kirk Richards and Doug Fryer. And serious collectors come down from Salt Lake and other places. And there’s an in-person auction, where you can silent bid; the bidding goes on all day long, getting really heated near the end. It ends at about 2 pm, and that room in the old school house is just packed with people almost enjoying the sport of seeing final bids. People are allowed to bid as long as they want on a particular table, with people battling it out and the prices go up. Half of the money for those bids goes into a charity fund that is used now to restore other houses and outbuildings in the town. And so the school is done. Now people can apply for grants to restore old cabins or homes and things. So you know, everyday people who otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford it can invest in that historic preservation. I’ve been one of the organizers of the art show and auction for about fifteen years. And so it’s fun to be in touch with all these artists from around Utah. Many have ties to Spring City, others have just heard about it. And we don’t jury the show because we don’t want it to feel exclusive. So even little kids will submit something on occasion. Some high school kids that are aspiring artists have participated—it’s a cool entry into that world of shows. In addition to the auction, the artists will bring three of their own framed paintings that they can put on the walls around the auction, and so you have the opportunity to buy original art off the walls. But I can’t believe the amount of money we earn every year from the auction and the art on the walls, like it’s in the tens and thousands of dollars, $30,000 to $40,000 that goes towards the Spring City historic restoration fund.

How did you get involved with it?

So when I was a teenager, my parents moved from Provo to Spring City and bought an old Victorian era pioneer home that belonged to a family that owned the Schofield mercantile store in town. And they fixed it up. They were part of that early generation of people who wanted to preserve these old homes. So I got introduced to the town as a teenager. I took art classes from some of the local artists at Snow College, when I was an undergrad, and then after graduate school, I came back and lived in Spring City in that home for a couple years and became familiar with the art scene in town and got involved in the show. And then I was asked to take over the show about five years later, and be the liaison or the organizer for the art side of things. And there are some famous artists who live there. It’s becoming known as an art Mecca in Utah. You’ve got M’lisa Paulsen, Lee Udall Bennion, Ken Baxter, Lynn Farrar, Susan Gallacher, Kathleen Peterson, Doug Fryer, Randall Lake, Michael Workman, Osral Allred, who’s since passed away but he used to live there. And a lot of artists have even moved there. It’s really good for plein-air painting. There’s a plein-air show every September. So you have the art show and Art Squared in May, and then in September, there’s a plein-air competition, where artists from all over Utah come to Spring City and paint for three or four days together, and then show their work.

And would you say it’s the show that has turned Spring City into this artistic Mecca? Which came first?

I think that the first thing that arrived was a guy named Craig Paulsen, and maybe some of the local Snow College professors like Osral Allred and Gary Parnell, who were invested in historic preservation—the architecture, the buildings, the homes, and thus were able to tap into national grants, the historic district designation, they got all that in place. And that attracted a lot of people from the art scene who would also overlap with the historic preservation scene. So you get graphic designers and home designers and artists who buy a second home there or move there. And it just so happens that they have a creative aspect to their career. And so the preservation brought the artists, it got that reputation, and the two work in tandem now. There is a little bit of tension in the town between the historical preservation crowd and art crowd, and the locals. Well, everyone’s a local now. Many of the art related people have been there for thirty, forty years now. But there is still an older segment of the town, that are the original farmers and founders and their descendants. And I would say, a bulk of them now embrace and appreciate the historic designation in the art community. But there’s maybe a minority that resents what they see as the uppity, Bohemian quality of that scene. And they’re a little bit irritated by all the tourists that come in, and maybe the rising home prices, because a lot of wealthy people see the town when they come down for these events, and when they buy up the old homes, it kind of crowds out the kids in these working class families that otherwise might have stayed there. There’s a little bit of tension with that.

Do you still have family there?

Yes. My mother-in-law, Shirley McKay Britsch, who is also an artist, owns the Squirt building, which is the mercantile building. And my brother, Stan, has an old barn home that he lives in with his wife Gwen down there. They’re also involved with the historic stuff. I guess I get treated like an honorary citizen because of my history of having lived there and having been involved in the yearly show.

I'm curious about historic preservation. What do you think is its value?

Well, we’ve had kind of a spotty record in the United States of cherishing and respecting and protecting a lot of our historic buildings. A lot of old town sections in cities, during the Modernist era, were just flattened in the name of progress and efficiency. We’re living in a postmodern era right now that wants to recycle and pay tribute to older styles and traditional materials. But then there’s just actual legal preservation that you occasionally see emerge in a place like Spring City or Park City, with building codes and grants to protect things. And I think we understand our own history better. We appreciate our own heritage. I think for even our own collective mental health, being able to commune with places like that that aren’t flattened, or just erased, by progress and overdevelopment is healthy. Maybe you do live in a busy part of the Wasatch Front, and that’s just necessary, all the high-density housing just to cope with multiple generations that need to live somewhere. But if you can set aside an area, that’s almost the equivalent of a human national park. If you preserve earlier modes of living, appreciate green spaces that are open or agricultural spaces that remain somewhat unchanged, then you can escape from collective stress or individual stress. There’s all this happiness research that talks about time spent in quiet green spaces being essential to our own mental health. And Spring City qualifies as this slightly dilapidated environment, where nature and farming culture are in a sort of détente, where neither one really seems to have complete control. The grasses and trees are always sort of encroaching on the outbuildings, and it doesn’t feel overdeveloped, a lot of the streets are dirt streets, it feels a bit more unpolished in a positive way. It gives you a taste of slowing down, not overdeveloping, keeping in touch with agricultural green spaces. I wish we did more of that in Utah. For example, all the orchards that Orem used to have, none of them have been preserved, nobody had the foresight to say, let’s just say that this number of orchards will always be subsidized as a part of our heritage. Wouldn’t that be cool? When I was a teenager, the whole town was orchards.

I’ve just been thinking, because of efforts to preserve the old Provo Temple, about how we might more effectively articulate the benefits of preservation. As in, how do we move beyond just saying ‘this is an old building therefore it’s worth preserving.’

Yeah, what are the deeper reasons we all could agree upon. There was a community effort at the center of Spring City that got both the chapel and the old school preserved. And it seems that everybody benefited from that; it wasn’t just a rich person having the money to preserve some cool pioneer home, but the entire town, and even people beyond the town who visited on a regular basis, people who left Spring City who grew up there or who have family from Central Utah, they all kind of make these pilgrimages. And they seem to be energized by reconnecting with those preserved spaces. Think of the generations of people from Spring City that went to school as children at that elementary school that can now return and see it in its full glory. What a cool touchstone. So maybe there’s some way to articulate the democratic, collective communal benefits, right, of these buildings that serve a lot of people. The town itself maybe, you know, has collectively been preserved and then opened up regularly. There’s the democratic quality of the home tour, of the charity auctions, of the grants that anybody can apply to to preserve even humble outbuildings. Like ugly sheds. That’s kind of cool, isn’t it? It really expands the scope when you think of the outbuildings and the town as a whole, as a historic district. Places in Europe have done a much better job of doing this kind of preservation, and it has fueled really vibrant tourism industries, and preserved the natural beauty of towns and regions. And we just need more of that. Spring City is a gem that feels almost like something you’d see out of Europe.