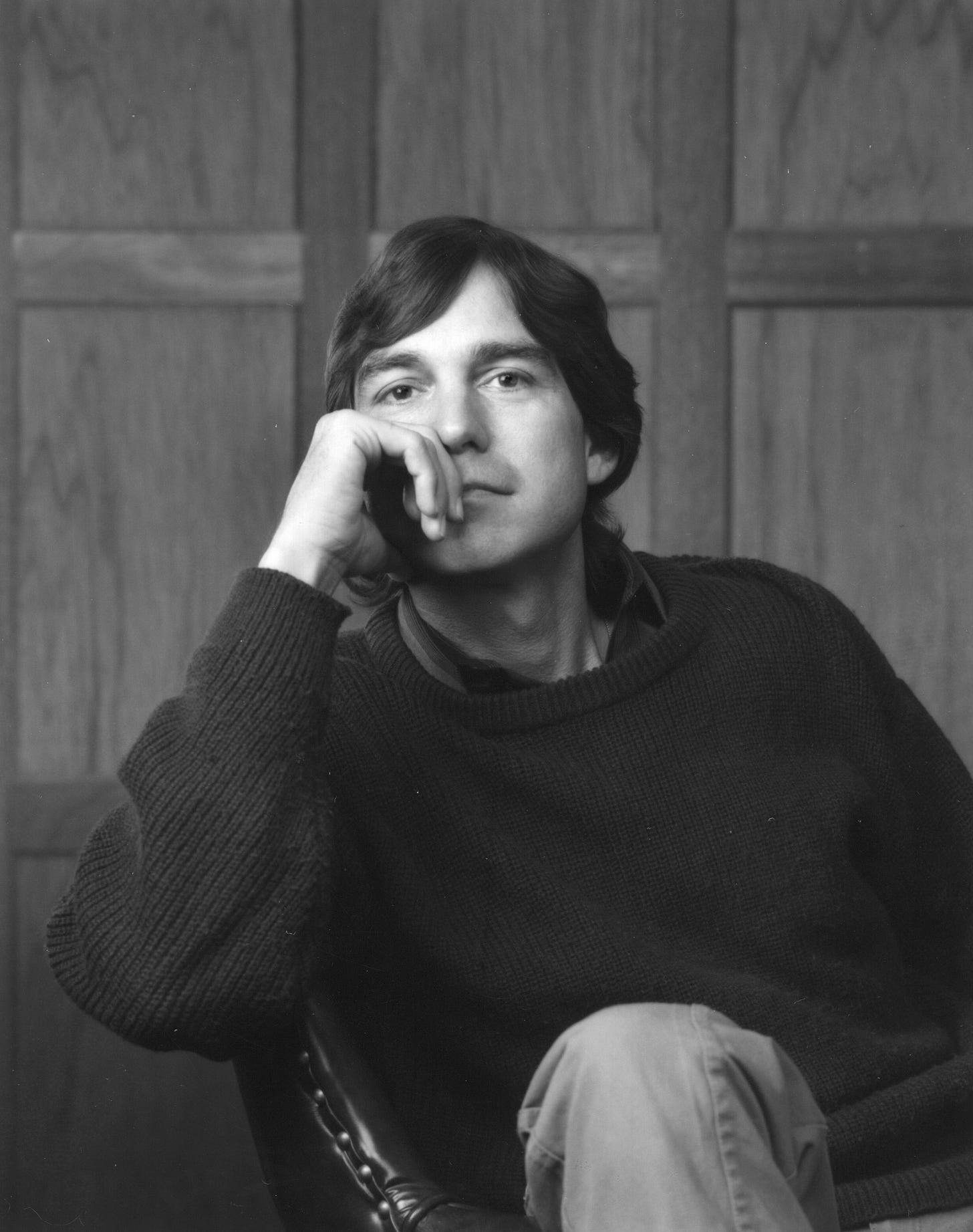

D. Michael Quinn: Disciple, Scholar, Troublemaker

The root of the historian's conflicted relationship with Latter-day Saint leaders was not his controversial research agenda but rather his unabashed faith

Every community needs elders to truly thrive. As a queer Mormon, I am constantly searching after those who have already tread my chosen paths. This is no easy thing to accomplish. Between the AIDS epidemic and the past policy in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints of encouraging gay men to enter mixed-orientation marriages, queer Mormon elders are hard to come by, much less ones who left a rich record of their journey. Mormon historian D. Michael Quinn is one of these rare figures. Quinn was one of the September Six, a group of scholars who were excommunicated in September 1993 for their academic work. In 2023, Signature Books published Chosen Path, Quinn’s sprawling, stream-of-consciousness autobiography, giving us intimate access to the inner life of this gifted and controversial member of the new Mormon history movement.

As I read through Quinn's meticulous self-chronicling, I was caught off-guard by how much Quinn and I have in common: we are both queer intellectual Mormons who can speak German and have a penchant for causing trouble. But beyond such superficial identifiers, I found Quinn to inhabit the same stubborn in-between space that has defined most of my adult life. My friends and peers don’t often really understand my simultaneous loyalty to both the queer community and the church. As a BYU student for the past four years, I have managed—sometimes more successfully and sometimes less—to walk the razor edge between orthodoxy and heresy. Like Quinn, I have received simply too much confirmation of God's hand in the Restoration project, and studying the church's problematic history has only strengthened my conviction that my faith tradition has been formed and nurtured by deeply human and sometimes ill-intentioned Christians who nevertheless accomplished some portion of God's redemptive plan for His children.

Sometimes, for myself as well as for Quinn, it seems like it would be so much easier to just leave the church alone, to withdraw from the world and give up any loyalties. But in this regard I aspire to Quinn's gravely funny self-identification as one who is “sensitive enough to the human condition and the pains of others to yearn to bind up wounds and comfort the afflicted, and (I guess) afflict the comfortable.” For some of us, especially the marginal, the call to serve the church means making people uncomfortable, causing a good sort of trouble, and risking expulsion.

In Quinn's case, it is notable that many of his once-controversial research topics—post-manifesto polygamy, for example—are now, only a few decades later, openly discussed by the institutional church. The Saints volumes, the Gospel Topics essays, the church’s two-volume history of the Mountain Meadows Massacre—all are fruits of trees that were planted by Quinn and his fellow new Mormon historians. While it might be tempting to assume that Quinn would have an easier time at BYU—where he worked as a history professor during the 1980s—or in the church today, I think he would still be challenging. The real core of what made him so disturbing to some church leaders at the time was not simply his areas of research but rather, more paradoxically, his unabashed faith. If Quinn were actually antagonistic, he could've been brushed aside as a reactionary ex-Mormon. Unfortunately—for those who would’ve liked to—he was too good of a critic and too good of a disciple to be discredited as either. Since his missionary years, he’d clearly understood his spiritual gifts, writing: “I began to understand faith as a mysterious gift. Especially my faith. . . . And as a concealed queer, I had my gifts. Faith was one. Empathy was another.”

While a historian by trade, Quinn always saw himself first and foremost as a disciple. In January 1966 he wrote, “I don't want to be looked up to as a great scholar or scriptorian, and have others look on in awe. I want to be down-to-earth, warm, simple, and not have so much respect that people are hesitant to be themselves around me.” And yet, it would be impossible to say that he did not relish in the trouble he caused, especially later in his career, when he would often speak bluntly about church issues to mainstream media outlets. Quinn no doubt took some pleasure in his habit of poking the institutional bear, even when it put his career and church membership on the line. But I’m not so sure that this need be such a resounding disqualification in evaluating the spiritual import of his work and research.

I believe that one of the best ways to describe Quinn's unique mode of interaction with faith and inquiry (his disciple-scholarship) is via theorist Judith Butler's notion of “trouble.” In the preface to her seminal study on gender performativity, Gender Trouble, Butler writes that, “the prevailing law threatened one with trouble, even put one in trouble, all to keep one out of trouble. Hence, I concluded that trouble is inevitable and the task, how best to make it, what best way to be in it.” Particularly for queer Mormons, whose very existence causes trouble, the most honorable path is that which prioritizes making the best kind of trouble. Call it the queerest path. Especially when seen in conjunction with Quinn's unwavering faith and commitment to the church even after his excommunication, such troublemaking can only honestly be characterized as the product of deep love.

But to be frank, Quinn's loyalty is still an enigma to me. It is hard enough for me to stay within the bounds of the church in 2024; to imagine navigating queerness in the church during the latter half of the twentieth century is truly baffling. Looking back at Quinn as a spiritual forefather, my chest tightens to think of all the sacrifices made, all the suffering endured. Quinn writes very little about the last twenty years of his life after his excommunication because, in his own words, “I want to delay such an account until I've had a long-term relationship of love and intimacy with another male.” But that was, tragically, the last thing he ever wrote in his autobiography. Ultimately, I am convinced of the value of faithful troublemaking, especially when done with the incredible academic rigor demonstrated by Quinn, but I can’t help but see that the greatest victim of his precarious, lifelong tightrope-walking was himself.

And maybe this is the greatest lesson that I am meant to glean from Chosen Path as a queer Mormon: make good trouble but beware the impulse to sacrifice your own well-being along the way. Quinn was so concerned with his crusade that he perhaps forgot himself in the mess of it all. After being fired from BYU and ending his marriage, he wrote, “I gradually resumed dreaming in color. For at least fifteen years before 1988, I dreamed only in black and white and rarely remembered dreaming at all. It's so different now.” I, too, dream of “a long-term relationship of love and intimacy,” and I hope that my faith in a God of Johannine grace will allow me to give love—for myself, for a lover, and for the world—the final word after I've made trouble enough.

Luka, I enjoyed your thoughts about Quinn. I also noticed you are an "avid bicyclist." Are you aware of BikeWalk Provo? It seems like it would be an organization that would benefit from your involvement and that you ought to be involved in.