I Was a Stranger: Megan Mukuria and ZanaAfrica

An interview with Megan Mukuria, the founder of ZanaAfrica

I Was a Stranger is a new series in which we interview and amplify charities, NGOs, and nonprofits. Learning about issues surrounding peoples and cultures locally and globally can expand and inform personal and collective Christian practices. We hope this series will also inspire people to give in ways they hadn’t thought of previously.

Our first installment features Megan Mukuria, founder and CEO of ZanaAfrica.

Megan grew up in Greenwich, Connecticut. From an early age, she became interested in diverse stories, cultures, and experiences. Raised Christian, Megan often questioned the disconnects she saw between theology and practice within organized religion. She attended Harvard University, where she had a personal conversion to Christianity and was led to various experiences that reinformed her priorities and changed the direction of her life. She went on a non-evangelical service project to Kenya one summer working with street children and was emboldened to take a completely different life path. Megan returned to school, dropped accounting, and took Swahili. She abandoned her thesis and took courses on liberation theology and child protection. As Megan put it, “I just let myself have the freedom to learn what I wanted to learn and not what I thought I should be learning.”

When she was 23, an NGO invited Megan to return as their resource mobilization manager and she has been living in Kenya ever since. She is the founder and CEO of ZanaAfrica.

What are some challenges about teaching women and girls in Kenya about sexual and reproductive health/ rights?

Kenya is sort of a microcosm of any other place. Right now, two out of three females in Kenya can't manage their periods with dignity. They either don't have any pads, or they don’t have the ability to access enough every month. The pads they can afford cause burning and chaffing.

Just the other day, we were in one of the informal settlements giving out pads to high school girls and many had never used a pad before: they didn't know whether the sticky part went up or down in their underwear.

During the first year of COVID, around 380,000 girls got pregnant. Two in five girls between the ages of 14-19 are pregnant or will be pregnant. If you have your first child during that window, you're more likely to have two or three by the time you're 19.

When we did our big two-year randomized control trial in Kilifi [a coastal county], we found that the average age for first-time sex was 12.8 years old, usually with a male five to ten years older. There's a huge power dynamic there without consent.

In the school system, there are issues with violence against children and a lack of education on sexual and reproductive health and rights within the curriculum.

In some communities, men will give a necklace to a girl to “claim her” in a ceremony called beading. It’s like a promise to pay a dowry. Once beaded, the man can take her even before she has menstruated, or when they need help around the house, at his leisure.

In indigenous cultures, there are rites of passage every seven years for children transitioning into adulthood. Boys ages eight or nine and girls who start menstruating go through a rite of passage and become young men or young women. It involves a fundamental introduction to adulthood. It helps children understand the value and meaning of womanhood and manhood—the freedoms and the responsibilities. In Kikuyu, there's actually a term for restricted sex– how far is far enough sexually and how far is too far. It’s a language of boundaries because they understand that people's hormones are going crazy. They need to figure out relationships, but they need to do it in a safe way without unintended consequences like pregnancy and STDs.

Colonialism stripped away the best of these indigenous cultural rights of passage and rituals during adolescence but didn't replace it with anything. Now there’s no alternative. Where there is anything, the narrative is often to look away from Afro-centric processes and see Euro- or male-centric as superior.

What inspired you to found ZanaAfrica and how did it start?

When I was invited back to Kenya in 2001, I bought a one-way ticket and worked with street children for five years. We took the kids out of informal settlements [slums] in Nairobi and moved them into the rural area, so they could reclaim their childhood. We had a lot of downtime at night and they'd ask questions about their rights, relationships, safety, and choice.

Almost all the other adults couldn't or wouldn't answer their questions. Either they didn't feel that they had the right answers themselves, or they felt like it was going to promote promiscuity. But these are kids who'd been on the streets! They'd been raped. They'd been in sexual relationships; they were probably much more experienced in these things than the adults themselves. I don't think the adults quite knew how to deal with that.

I would answer all their questions from an honest, rights-based framework and talk about what that meant for their choices, safety, and relationships.

Over those five years, I saw a stark difference between kids who had answers to their questions and kids who didn't. Kids were completely derailed if they didn't have information given to them. I've been at 18 year-olds funerals because they died of AIDS. It's a life or death situation. And if they are living but lacked the answers, they’re 19 now with five kids and are maybe being beaten. Gender-based violence is very prevalent and culturally accepted (although this is a norm we are changing).

At the same time this realization was occurring, I was putting together our budgets, looking at the cost per child by gender, and trying to raise funds. I noticed sanitary pads were the second biggest cost every month after bread for girls. Pads are a root cause of poverty for girls and women, contributing to generational cycles of poverty. I wanted to create an organization that combines those two things: a sanitary pad business that would fund a sexual health curriculum.

I tried to start that within the NGO where I was working, but it was a bit too ambitious for them. I had to end up creating my own organization, which I did very reluctantly.

In 2004, female MPs [government leaders] in Kenya repealed value-added tax for pads and tampons. They were the first in the world to do it. Today, Gillette razors are waived as a necessary product for men in the US, but pads are still considered a luxury good. Pads are in the same category as lipstick! Learning about this gave me the push to start the organization.

The word zana means “tools” or “weapons” in Kiswahili. For us, zana is about crafting tools for sustainable poverty alleviation. It’s about giving youth, especially girls, the tools they need in life. Ultimately, it’s about girls being able to become who they want to be, and being the tools the world needs for global transformation. They're the ones who can chart their own paths out of poverty, and change nations. ZanaAfrica started officially in 2007.

What is the importance of teaching within a rights-based framework?

Operating within a rights-based framework is a journey to liberate ourselves from the negative social norms that tell us that menstruation, bodies, and desires are dirty and shameful; you have to hide them and not talk about them.

From this framework, you learn about your rights, personal values, beliefs, and choices. You're not prescribing for people what they should do, you're helping them to think about what this context means within their cultural framework, and then giving them the permission to make their own choice.

For example, if a girl feels pressured by her boyfriend to have sex, you help her figure out what the choices are and the potential consequences. You talk about the spiritual connection of intimacy, physical arousal, consent, and other options. You start early, in age-appropriate ways. Speak openly, present facts, and then facilitate decision-making because it's their own choice. When we started to create our curriculum, we created a framework of “learn-believe-choose.”

Working within a rights-based framework is the most dignifying and liberating way for humans to interact with one another.

What have been ZanaAfrica’s main struggles?

The biggest difficulty was this issue was not on anyone's radar and menstruation was (and still is) such a taboo subject. I felt like people would see me and say, “Uh oh, the uncomfortable lady is coming—pretend you don't see her.” I spent five years simply trying to stay funded by doing side hustles. We got our first small grant in 2009. We didn't get any more money until 2012.

I launched the National Sanitary Towels Campaign with the Ministry of Education and other people here in Kenya. I picked up the phone and tried to network, to use my Harvard name—whatever it took—cold calling the MacArthur Foundation, Ford, pick your big name. Nobody was dealing with this issue at all.

What has ZanaAfrica already accomplished?

Right now, the entire world depends on fast-growing pine trees mainly from the United States for their pulp products (think: toilet tissue, kleenex, paper, pads). It's a commodity that's rapidly escalating and is the biggest cost driver of pads. To mitigate that cost, companies add a superabsorbent polymer, exactly what you find in a baby diaper. It doesn't biodegrade and it’s toxic. There aren’t many affordable bioplastics, and most of them photo-degrade but don't biodegrade, which means they just microscopically populate the soil.

In the last decade, we created patents for nine different types of pad pulps. These pulps will be used for our pads, maternity pads, adult diapers, etc. Once used, our goal is that our disposed products will be completely biodegradable. Additionally, we are working to introduce a menstrual cup. Our vision is for someone in rural Africa to be able to visit their local kiosk, buy our products, and give dignity to their loved ones or themselves without destroying their environment.

Since we started selling our pads, we’ve been rapidly expanding across Kenya. We are in four counties and serve 50,000 customers per month. Historically, we’ve served an estimated 180,000 schoolgirls with four or more months worth of pads. Importantly, on the back of our pad packs, we promote education and links to reproductive health partners, which were used by 10% of all customers during COVID.

We are really good at encouraging communication surrounding social and behavioral issues to understand what is preventing society from taking action. We then develop written and verbal communications to help overcome those barriers so that people take health actions that are in their own best interest.

Because of this, we’re now piloting an education hotline because humans need personal connections. People should have an option (dignity through choices) to talk with an anonymous chatbot or to pick up a phone and have a compassionate conversation with someone whose full-time job is just to listen, answer any questions, and direct them to the right resources.

In Western Kenya, we're using our hotline to amplify a drive for cervical cancer screening, and HPV vaccinations. Kenya has an incredibly low vaccination rate and the leading causes of death among women are cervical cancer and HPV.

Blood drives are another big challenge because there's a lot of suspicion around who's using your blood and for what purpose. Witchcraft has scared people off, so a lot of people die because doctors don't have enough blood to give them during childbirth or accidents. We believe we can use our expertise and our toll-free number to offer a methodology to change these and more health outcomes while building our Nia brand.

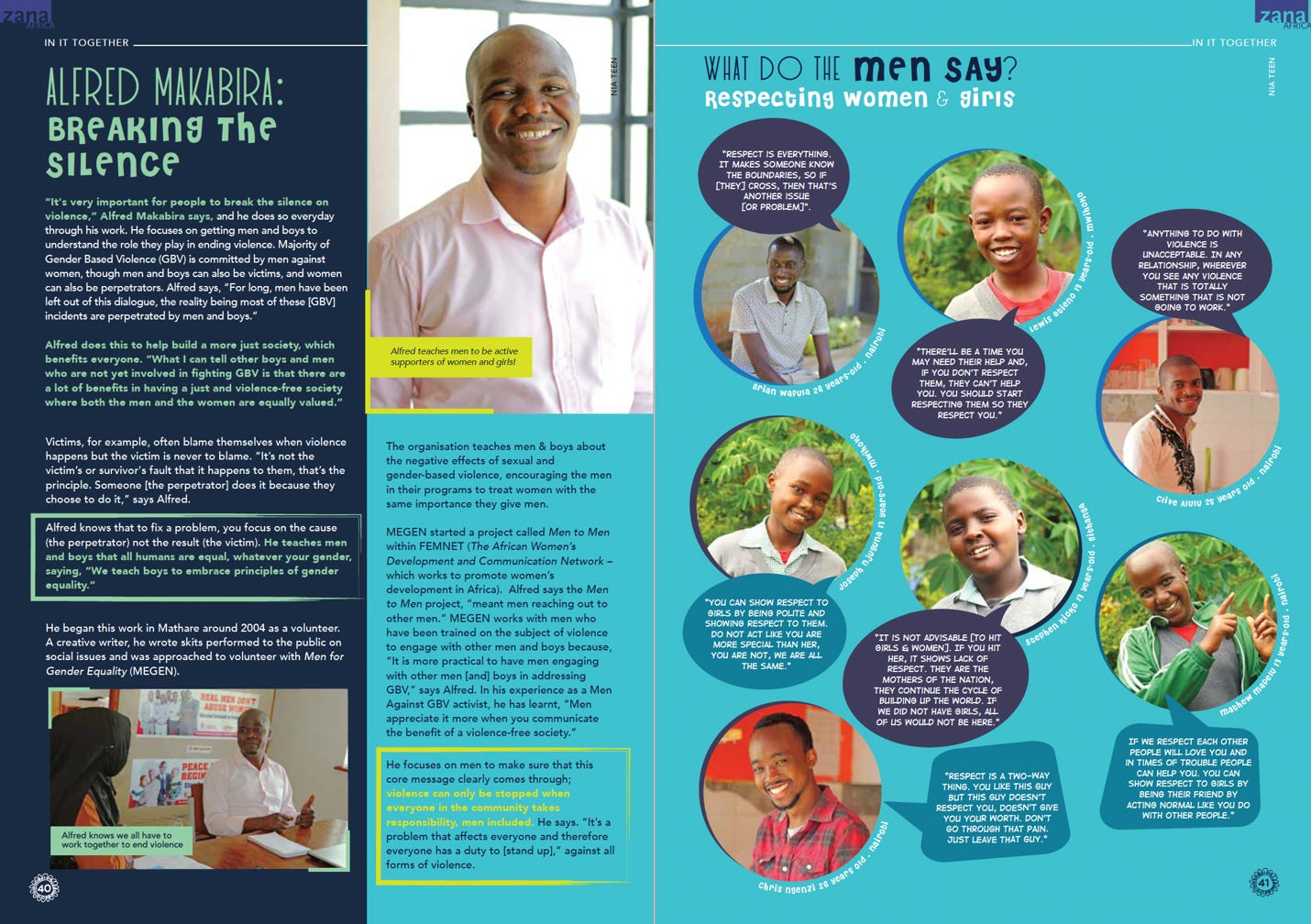

As it was always about pads and health education, we created an amazing reproductive health curriculum. We have learned that storytelling is very prevalent in every culture in Africa, and really the world. People read themselves into these stories in a way that is depersonalized enough to make personal issues less threatening and more interesting. So, we reimagined a textbook as a magazine for our curriculum.

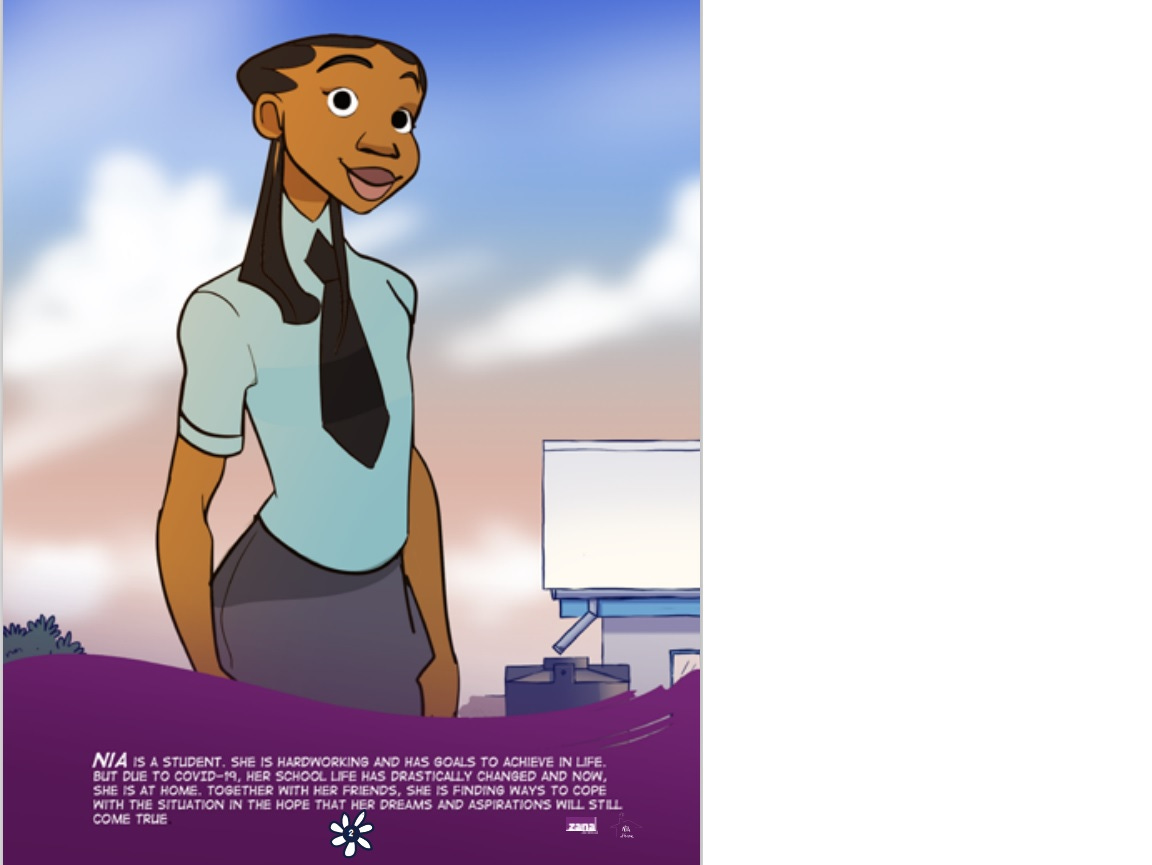

Our NiaTeen magazines have all the rigor of a textbook, but the treatments are story-based, comics, and real-life stories. Girls actually see role models that they relate to. We have proven outcomes (measured in a two-year randomized control trial across 140 schools) in changing gender norms and menstrual norms. We change knowledge about family planning, myths about STDs, and youth retain how to avoid teen pregnancy.

We're now in discussion with the Kenyan government to put Nia into the Kenyan curriculum. That would be transformational. We'd have 11 million adolescents go through the curriculum—like a new rite of passage. When studying the efficacy of the former Nia magazine, there was a 98% knowledge retention and sharing rate and the rates are even higher now.

Where do you want ZanaAfrica to be in five to ten years?

Note: This section contains educational anatomical illustrations of male and female genitalia from the NiaTeen magazine.

I'm hoping that in the next few years we will be in every county in Kenya and will have expanded in other countries. I want to see us making pads, diapers, maternity pants, and other products here in Kenya.

In the next three to four years, we want the Nia hotline to be a one-stop shop for all health issues. Nia means purpose or intention. We believe everybody has a purpose. Purpose is found when there is clarity. Clarity comes when every kid in Kenya has answers to their questions so they can make safe, informed decisions during adolescence and become adults who aren't traumatized. Purpose is personal and discovering that independently is a joyful experience.

I would love to serve 10% of menstruators on the continent and have our curriculum be in other parts of the world because the knowledge gaps are the same everywhere. Taboos are very similar in so many different cultures and the experience of adolescence is universal. If Nia magazines had stories from different cultures, it could help address a lot of issues surrounding racism, sexuality, and body image and help reunite humanity through their shared experiences during adolescence.

How do you establish trust among girls and women?

The health curriculum is currently led by community health volunteers who are young, trusted people in their community between the ages of 20 to 28. It will eventually be taught by teachers. There are some ways in which the curriculum helps to lay out what is a safe space and how to make the classroom a safe space.

We always start our courses with kids writing questions anonymously. Then we answer them! There's so much trust that's built-in with that system. It provides an honest, rights-based framework and gives answers to questions they’ve never had answered. In any classroom we visit, all the questions have the same scope, from rape to consent, to peer pressure, to what is normal for discharge in underwear, to period and ovulation questions. After every session, students are invited to write down additional questions and put them in a box. Those questions get answered in the next session.

Our curriculum requires a strenuous interview process to ensure we are getting the right people and train them correctly. It’s been exciting to figure out how to codify this at scale and help people who don’t yet have that rights-based framework to adopt it, to work through their own trauma so they can be safe people, and to make sure that it's a relationship-based process while at the same time having standardized outcomes.

Where are some things you've learned since starting Zana Africa?

American culture loves the narrative of the individual Savior, but Jesus had twelve people. Jesus had a mission, but even He got some folks together and said, “We're gonna do this thing—we're gonna change the world.” We've got to break down this individual savior narrative because it's toxic and antithetical to true social change.

I'm where I am because so many amazing people have joined up with me and entertained my crazy vision. They brought it to life in ways that I couldn't have. I’m not a material scientist. I'm not a designer. I can't draw comics. I can't come up with these storylines, but I can team up with people who do.

Leadership is really lonely. Learning to be okay with being misunderstood and rejected is crucial. Often, people feel like they're contributing if they're criticizing; poking holes five ways to Sunday into my dream. It’s an American cultural value I have learned to put aside.

Viewing perspectives as cultural norms instead of all-encompassing truths has been really liberating for me when having hard conversations and trying to evoke change. Just because your reference community does things one way, doesn't mean that's the only way or even the right way.

I think the biggest realization we had was from our randomized control trial: when we changed menstrual norms by providing products and helping to confront these taboos then girls experientially changed their understanding of what was possible.

One cultural myth is that girls can't play sports during their periods. Actually, sports are good for you when you're on a period because it reduces your cramps. So you give pads to girls and say, “Go run, go play sports.” Then they do, and they're like, “That was amazing!”

Then they start recognizing and questioning other norms, like “Why do I have to do all the household chores? Why can't my brother also pitch in? Why is it okay for my dad to beat my mom?” They start to challenge what is being taught.

If you can help break and challenge these menstrual norms, whatever they are in your own culture, it can help equip teenagers to see them within the human rights-based framework. They can see different ways of doing things as a culture, as a family, as a community, that are better for everybody. I think that's the most important contribution that we're making to the world right now.

How do you work with locals to inform the work of your foundation?

The locals are the ones that get it. I defer to people a lot. We do desk research, but everything starts and iterates with focus groups and surveys so it's co-created. To understand the baseline, we ask people what they want and feel. Then I work with people smarter than me in different areas, and we figure out how to make change happen.

The illustrator of our magazine, Naddya, shaped her work to meet the feelings of the rural and urban Kenyan girls that comprised the focus group. She created three different versions of illustrations and talked with girls about what they liked and what they didn't. For example, our main character, Nia, is personified as a freshman. Naddya had created Nia as slouchy, kind of rebellious, cool. The girls in the focus groups totally rejected that persona, “No, she needs her socks pulled up! She needs to have her fingernails clean. She needs her tie tied nicely (in Kenya everybody has uniforms, including ties). Her hair has got to be neat. She's got to be a good girl.” This learning reshaped Naddya’s process for creation, and it’s been amazing to see her growth as a professional.

Helping my team take on a mindset of challenging their own assumptions and developing products and services with the end consumer in mind is my role. I don't care about the how, I just care about the why. If you ask the right why the how answers itself.

What can we do to help ZanaAfrica keep up its momentum?

Prayers and encouragement. We are working with the government and they really want to work with us, but they don't have the money to do it. If we want to get into the national curriculum, we need more financial resources, and we need the government to remain aligned with us during this transition year (it’s an election year).

Jesus started His ministry in Judea. He said that they were going to eventually preach to the end of the world, but they had to start locally. Work locally before trying to engage internationally. It’s much harder but much more impactful to deal with the poverty, systems, and social norms in your local community.

Conversations are equally important. For women, when was the last time you talked to a male in your life about menstruation? Is that conversation normalized in your circles? Have you ever talked to your children or your nieces and nephews about their questions? Be that safe person that they can go to to ask questions as they're growing up, and respond within a rights based framework. If everybody did that, the world would be in a better place in five to ten years.

Lastly, donate! You can support a kid or a school. You can help support sexual health curriculum development for government education. Donate supplies to local women’s shelters. Usually, the number one and two things shelters need are socks and pads.

What advice would you give to someone who was looking to make a difference in the world or looking to start a foundation?

If you want to make a difference in the world, ask yourself what makes you come alive. So often, I feel like our single cultural narrative makes us dampen that yearning in our hearts. I had so many friends when I moved to Kenya who said things like, “I wish I could have done that, but now I have a house!”

I'm like, “Well, sell the house!” I remember an older woman who had this big, beautiful house on the waterfront in Greenwich. She said her heart was in Tanzania doing ministry, but she couldn't leave her house.

“I am in a gilded prison,” she said to me. That phrase, gilded prison, is seared into my brain. Making those choices that make you come alive, saying yes and yes early on liberates you. It prevents you from getting trapped later. Listen to your heart's yearning and answer it. Overcome your fear to say “yes.”

Follow ZanaAfrica and NiaTeen magazine at @niayanguke on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

Recommended Media:

Most of Megan’s recommendations are about seeing ourselves differently, learning new narratives to challenge our own, and stepping into our authentic selves.

Books:

How to Change the World, by David Bornstein

The World Is As You Dream It and The Secret History of the American Empire by John Perkins

Culture Making: Recovering Our Creative Calling and Playing God by Andrew Crouch

Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church, by N.T. Wright

Their Eyes Were Watching God and Barracoon by Zora Neale Hurston

Television Series:

PBS series: Africa's Great Civilizations by Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr

Free on Amazon this month: Black History, Black Freedom, and Black Love

Podcasts:

How To Citizen with Baratunde and We're Having a Moment by Baratunde Thurston

Malcolm Gladwell's Revisionist History

Do you have a recommendation for a charity, NGO, or nonprofit for us to interview? Please reach out to us at utahmonthly@gmail.com.

Great interview! I am interested in the new pulps ZanaAfrica is developing. I feel like they have the potential to have international appeal and could potentially help fund their efforts on a big scale. I'm curious as to whether this is their plan, and we'll be watching their Instagram.