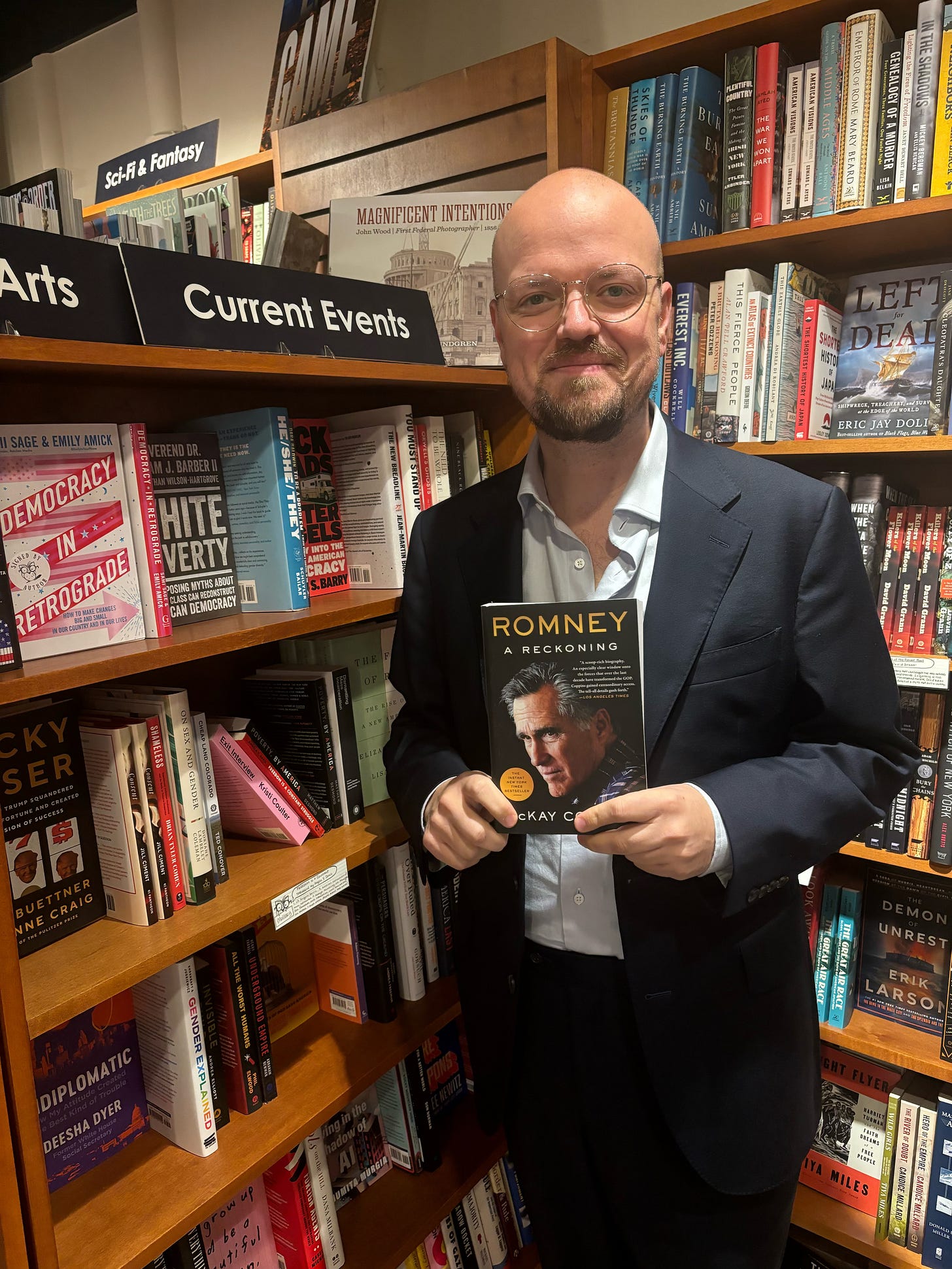

A few weeks ago, two of our editors had the chance to chat over Zoom with McKay Coppins, a staff writer at The Atlantic and the author of Romney: A Reckoning (Simon & Schuster, 2023), which came out in paperback earlier this week. During our conversation, we discussed the book’s reception, responses to Coppins’s December 2020 cover story on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Coppins’s recent reporting on Utah governor Spencer Cox. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

So the first question I have is just what's the reception been like of the Romney biography?

It was pretty overwhelming, honestly. I had been working on this book basically in secret for like two years. Very few people knew about it: my family, my publisher, Mitt, obviously, and I think one or two of his staffers and that's basically it. We didn't want to announce it too early, in part because he didn't want his colleagues to start wondering about what he was telling a biographer. And frankly, I had the sense that he might be more comfortable and candid if this project wasn't public. But spending so much time working on this without really telling anyone, I did start to wonder at certain points if anyone was going to care about a book about Mitt Romney. (Mitt himself would constantly joke that no one would want to read about a has-been like him.) And so it was really gratifying and unexpected that it got the reception it did; it got so much more attention than I possibly could have imagined.

It sold well, and the reviews were really positive, which is always nice. But I think the stuff that was most meaningful to me, and I think to Mitt, was the readers who reached out privately to say that reading the book had caused them to reflect on their own tendency toward rationalization, and the tension between ambition and principle, and that it caused them to recenter themselves and pay more attention to their conscience. I think that’s one of the main themes of Mitt Romney’s life, and of this book. So, those response were the most rewarding.

Gotcha, that’s interesting. What was Mitt's reaction?

Well, he read a draft of the manuscript before it was published. That was kind of the deal we made. What I had pitched to him at the outset was: I want full access, complete candor from you, and I want to maintain editorial control, meaning, I get to choose what goes in the book, not you. But I let him read it beforehand, so that if there was anything in the book he thought was unfair or inaccurate, I could hear him out in good faith and address it if I agreed that he had a point. I think given the level of candor and access he offered, it was more than fair to let him read it before the rest of the world.

And his reaction? You know, I've often wondered in the last few years how I would react if I were in his shoes. It’s no small thing to turn over all your journals, for example, to a biographer and to dump thousands of emails from your private correspondence on his lap and sit for dozens and dozens and dozens of interviews, and then let that person go back to their house and leaf through basically your whole life and turn it into a narrative that you may or may not completely agree with. I would have to imagine it would be pretty hard to then read what this other person has made of your life and career and choices.

I think the book is overall a sympathetic portrayal, though it often also contains criticisms and captures moments that he's probably less proud of. And so I give him a lot of credit for going through with it. I think he had a range of reactions after reading the manuscript, but where he eventually settled was, “This is your book. It's not my book. And I’m at peace with what you’ve written, even if I don’t agree with all of it.” Overall, I think he’s happy he did it—but you’d have to ask him! We still talk, and in the paperback edition that just came out, I have a new interview with him.

I will say a lot of people who reacted to this book were Republican politicians, or people in Donald Trump's orbit or people in the right wing media who read it as a grave betrayal. It really cemented his status as a villain to the MAGA world. There were people on the right who said really nasty things about him after it came out. Donald Trump weighed in, J.D. Vance attacked him. Mitt has been dealing with stuff for a long time, but I’m sure it wasn't fun.

But I’ve also heard from some of the people closest to him—his family, some of his best friends—who read the book and felt it really captured him, and I think they told him that, which probably mattered more to him than Trump’s review.

Jon Meacham has this grandiose blurb on the cover of the book where he calls you the “emerging Edward Gibbon of American conservatism.” Could you talk about what he meant and if that characterization captures your goals as a journalist at this point in your career?

It’s such a perfect Jon Meacham quote. Just some backstory: Jon was actually the editor of Newsweek when I started there as an intern right out of college in 2010. Newsweek at the time had a class of like fifteen interns that all started that summer, and he did a lunch with us where he answered our questions. I'm sure he had no idea who I was. But he's been very generous over the years. He's followed my career, and we were emailing a couple years ago about something else (I can't even remember what), and he said I'm so impressed by what you've made of your career. You've become the Edward Gibbon of American conservatism. And I joked that one day, I was going to ask him to blurb a book of mine, and he needed to include that line.

I was joking. But then when the time came and I actually asked him to read this book, he wrote kind of a long blurb, and he actually read it, which is always nice. Sometimes people (just a little industry dish for you here) who blurb books are doing it entirely as favors to friends and don't actually read the book. You could tell he had actually read it, which was nice, but he included that line, which I thought was funny, but also my publisher loved.

Do I consider that accurate? I mean, it’s obviously way over the top. I think what he means by that is that I've spent a lot of my journalistic career over the last, basically, fourteen, fifteen years chronicling the decline and fall of the traditional Republican Party and American conservatism, just like Edward Gibbon did with Rome, a slightly loftier subject.

I certainly don't think I'm the only one who has written on these themes. There are a lot of good journalists and authors who have tackled this issue in definitive ways, but I do think it's been a running theme of my work. And frankly, I think it's one of the most important stories of American politics of the last half century. What is happening to the Republican Party is a microcosm of American political culture's transformation and the rise of this new right nationalism and populism that's sweeping across the Western world. So, I think it's an important story to tell, and I'm certainly honored if anyone, let alone somebody like Jon Meacham, thinks I'm doing a good job of it. It’s not the only thing I write about, but I think it is one of the biggest stories in America.

Now a question about your Atlantic piece “The Most American Religion.” I remember seeing a photo of you interviewing President Nelson in the June 2021 issue of the Liahona. Then earlier that year, I was talking to a professor at BYU, a friend of mine, about your article, and he had remarked that his friends, who he didn't even think knew The Atlantic existed, had read it and were asking him about your article. So do you think that church leaders and members, more broadly, saw it as the kind of exploration of Mormonism, with all its complexities, that they wanted published in a prominent national magazine? What is your sense of the membership’s or the leadership’s perception of how the article did?

I think you’re asking two questions: What did the church leaders think of the article? And what did members more broadly think of it? On the first question, I think you’d have to ask church leaders themselves. I certainly don’t want to presume to speak for them. But just as a bit of backstory, I actually traveled out to Salt Lake City with the editor in chief of The Atlantic, Jeffrey Goldberg, nearly a year before my interview with President Nelson. We met with him and laid out our vision for this article, which would be pegged to the two-hundredth anniversary of the First Vision.

Jeff had been telling me for a long time that he wanted me to write a deep, long form exploration of Mormonism. He's just kind of always been fascinated with it, and fascinated with religion more generally. He wants The Atlantic—and I think he's been pretty successful—to be a national publication that takes religion seriously, not just as a political story, or a kooky, exotic phenomenon, which I think a lot of the secular press is prone to do, but as something that matters in its own right.

In our meeting with President Nelson, Jeff was pretty straightforward with him about the kind of story we wanted to do. And Jeff said something like, “We can't promise that this piece will steer clear of the more complex chapters in the church’s history or its current tensions, but the goal is to give readers an accurate, fair, and nuanced sense of what it is to be a Latter-day Saint, what the church stands for, and what it sees as its mission.” And he told them, “You have a unique opportunity here, because you have a writer who is a currently practicing member of this faith, and can write about the church from not just an academic or journalistic perspective, but also from a lived-religion perspective.”

So, I think we were pretty upfront with them that this would be a serious, complex piece of journalism, and the church didn’t seem afraid of that. There's some historical precedent for this. President Hinckley famously did his 60 Minutes interview [in 1996], where he answered tough questions for a national audience. President Nelson agreed to the interview after our meeting, and to his credit, he honored that commitment even after the pandemic began and he would have had every reason to cancel it. I’ll always be grateful to him for that.

As for how the broader Latter-day Saint diaspora reacted, I was pretty overwhelmed by the response. This article ran in December 2020: it was like ten days before Christmas, we’d just had a presidential election, Donald Trump was refusing to concede, the pandemic was still raging, the first COVID vaccines were being announced—there was a lot going on in the world. I thought there was a very good chance that the article would kind of get buried, that people wouldn’t be in the mood to read 9,000 words about Mormonism. But it ended up being one of the most widely read pieces I’ve written for The Atlantic. I got literally hundreds and hundreds of messages from members of the church, former members of the church, people who have known or been friends with members of the church, who said that they felt like they felt seen in the article. I found that really gratifying.

That's neat. Thank you for unpacking that. So this is switching to a different subject, not to give you whiplash, but I wanted to talk about your piece last month on Utah governor Spencer Cox. I was just curious if you could talk a little bit about his unexpected decision to endorse Donald Trump for president?

I'd been talking to Governor Cox off and on all year for a profile, and had no indication that he would ever consider endorsing Trump. He had been very critical of Trump. He had been critical of Trump's style of politics, the way that it kind of pollutes the discourse and makes us as a country more polarized. He’s been very outspoken on those issues, and also, I think, really articulate and insightful. So the endorsement came as a surprise to me, as much as it did to anybody else.

I went and interviewed him at the governor's mansion a couple days after his endorsement, and told him at the outset that I was going to play devil's advocate and just ask some very skeptical questions about what he was doing. And look, I thought his defense was interesting. He did not have to endorse Trump. If he was doing this purely for political-sellout reasons, he would have done it a few months earlier when he was fending off MAGA challengers in his Republican primary. So, he tried to make the case that he had reasons beyond political self-interest.

What changed for [Cox] was the assassination attempt on Trump in Butler, Pennsylvania. You can read all about it in the piece—he described it as kind of an epiphany moment for him. He feels if that bullet had just been millimeters to the right, Trump would have been killed, and America would have descended into something like a civil war. And he was encouraged by the fact that in the immediate aftermath of the shooting, Trump did not try to escalate things or make threats. So, Cox told me that what Trump needed to change his behavior and to exercise more restraint going forward was a different incentive structure. And he thought, ‘maybe if people like me, who have stayed away from him, decide to endorse him now, he'll see that there’s a political reward for behaving better.’

Now look, a lot of readers found that to be pretty naive. Some people thought it was outright disingenuous. In any case, this theory was almost immediately proven wrong. Trump has not tried to unify the country in the weeks since the shooting, he has not mellowed, he has not become more moderate in his temperament. He has not stopped saying outlandish, provocative things about his opponents. And so that part of Cox's calculation was just wrong, I think, and even he would kind of acknowledge that it's not working out the way that he hoped.

He still has a hope that by now having endorsed Trump, he will be able to bring his message of depolarization to Trump supporters, especially in places like Fairview, Utah, where he grew up, where he's been distrusted because he never endorsed Trump. I think the jury's out on whether that'll work, but in the meantime, there are real risks associated with hitching your wagon to Trump. You know, look at what happened at Arlington National Cemetery. Cox is now experiencing what a lot of other Republicans have experienced, which is that when you get close to Trump, even if you try to do so in the most principled way, you’re on the hook to answer for a ton of baggage.

Gov. Cox’s recent about-face is the biggest Utah-politics mystery in a long time. My working theory is that he’s preparing to primary Lee in a few years. Otherwise I’m dumbfounded by it.

Nice work on this interview, very interesting read.