Separation of Church and Party: Part One

Part one of a two part article exploring the historical, current, and global relationship between The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and politics.

Identity politics is a mechanism that brings people together based on a shared identity. While it can be a strength that affects positive change, there is also a risk of conflating and silencing intergroup differences. Many members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints justify always voting Republican. As refugees denied a homestead and an identity within the United States, early Church members were fiercely independent. It wasn’t until years after their painful incorporation into statehood and citizenship that partisan identity politics began to creep into Church discussions. Later, Ezra Taft Benson, J. Reuben Clark, and other conservative Church leaders used identity politics and religion as rhetoric against Communism, Socialism, and the Democratic party. Despite two of the three members of David O. McKay’s first presidency being Democratic voters, the re-writing of the Church’s welfare handbook in 1990, and several prominent Democrats being called into church leadership positions, members of the Church closed-off space for views differing from those of the Republican Party.

Without knowing it, many thoughts, beliefs, and decisions of members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints about current issues are based on Ezra Taft Benson and other right-wing leaders' opinions. Whether you agree with their ideas is not the issue. My purpose is to explain the history of the relationship between the Church and politics, where we are today, and what the Church’s relationship to politics looks like on a global scale. Education and intentionality are the antidotes to unconscious bias. For the last several years, there has been a mass exodus of American members, many of whom have felt there is no longer a place for them in our pews or our doctrine. That is simply not true. These inherited principles have been holding us back as disciples of Jesus Christ. It’s time we shun partisan identity politics within the Church and embrace our identity as members in the body of Christ.

I will be addressing this topic over the course of two different articles. The first installment will be an anthropological sketch to explore how the Church in Utah became the Republican monolith it is today. There have been articles and books that have discussed how and why the Church in the United States has shifted. The shift has been gradual, but most notably and rapidly occurred during Ezra Taft Benson’s time serving as a General Authority. In early Church history, a more conservative stance was formulated from the Mormon experience after years of persecution, reneging anti-racist, anti-slavery ideologies and replacing them with policies like the priesthood ban. Later, the fear of Communism and the enmeshment of politics and religion clinched the conservative identity of the Church in the twentieth century and beyond. I have done hours of research, read several books, and gone down a rabbit hole of internet searches. This article is a product of that.

The second article (coming soon) reflects the relationship between politics and the Church today, including nationally and globally. I have interviewed and spoken with several members who live in various places around the world. My eyes have been opened to the myopic political perspectives that American members have. Since the Church took a partisan turn in the mid-twentieth century, we have inadvertently alienated not only the members in the Democratic party but many members and potential members across the world. It’s time to let go.

Part One: Looking Back

A Progressive Heritage

One Sunday in Utah, a bishop stood at the pulpit, split the congregation down the middle using the central aisle, and said, “Everyone on this side of the aisle will vote for the Democratic candidate, and everyone on the other side will vote for the Republican candidate.” Years earlier, a prophet ran for president on a platform that, among a few other issues, centered around the liberation of Black Americans, criminal justice reform, and the federal government to step in and protect the liberties of minority groups.

The first story sounds like heresy, but it actually happened. The year was 1893, and according to David O. McKay’s biography, President Wilford Woodruff asked bishops to divide their wards politically to aid in attaining statehood. The second story is about Joseph Smith’s 1844 presidential campaign that was abruptly cut short with his assassination.

When the Mormon pioneers fled Missouri and ultimately ended up in Utah, they were not simply looking for “the right fit”; they were violently expelled from their homes and threatened with their lives. They were migrants, refugees that fled to Mexico for amnesty. As we know all too well, being a refugee is a devastatingly timeless problem that will persist as long as there is an abuse of power and an unempathetic or incapable government.

While women around the U.S.A are celebrating 100 years since the inauguration of women’s suffrage, Utah women are celebrating their 150th anniversary. It is perhaps surprising to learn that despite plural marriage's moral complexity, avant-garde opportunities for women became an option. Any marriage had to be consensual, and Utah permitted no-fault divorce (divorce without a cause). Compare this policy to the common law doctrine of coverture, which declared a woman civilly dead once she married, which many states still observed.

In an 1873 General Conference address, Brigham Young encouraged women to attend medical school and become doctors. Martha Hughes Cannon was a woman who was set apart in 1878 to attend medical school and become a doctor. She later received a degree in pharmacy and attended the National School of Oratory. She was a women’s rights activist who traveled to suffrage conferences around the country with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Martha became the fourth wife of Angus Munn Cannon and ran as a Democrat against her Republican husband (among others) and won in 1896, becoming the first woman state senator of the United States. A state senator, a doctor, a business owner, a women’s rights activist, and a mother, Dr. Cannon is an early example that women can be mothers and more.

For most of the early twentieth century, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the United States voted majority Democrat in general elections. They voted for FDR, Truman, and Johnson. Though his family was assigned to vote Republican in one of those political sacrament meetings mentioned previously, President David O. McKay worked hard to promote a politically neutral Church stance during his leadership. Unique to McKay was his special relationship with President Lyndon B. Johnson. President Johnson frequently contacted President McKay for advice. Recalling a conversation with President Johnson, Boyd K. Packer said, “He said, as nearly I can quote, ‘ I just don’t know what it is about President McKay… somehow it seems as though President McKay is something like a father to me. It seems as though every little while I have to write him a letter or something.’” They visited with each other several times, including when President McKay attended his inauguration with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, who performed. In part because of this extraordinary relationship, in 1965, LDS chaplains were no longer required to attend a seminary to work in the military.

Early Church Persecution

A gathering of sorts commenced. First, it was in Kirtland, Ohio, before they were expelled. Then it was Jackson County, Missouri, and shortly afterward, Nauvoo, Illinois. Each time, the locals in the area became threatened by this group of growing people, their strange, new religion, and their voting power. Fear of voting majorities and local government takeovers became justifications for persecution and even violence. According to W. Paul Reeve’s book, Religion of a Different Color, residents in Nauvoo and Jackson County began to distinguish themselves from their Mormon neighbors with a technique called racial othering. People claimed that though Mormons seemed to come from white, Anglican ancestry, their behaviors and beliefs made them “non-white.” Non-whiteness, or being denied whiteness, indicated denial of rights to citizenship, rights to autonomous power, and rights to personhood. Physical and behavioral characteristics began to be recorded about the Mormons to substantiate racial othering. Rumors about Mormons “mixing” with other non-white races began to circulate, furthering the hatred and prejudices.

In response, Mormons tried to prove their “whiteness” by shunning racial minorities in their own Church. Joseph Smith and other leaders published articles supporting racist dogmas about Black people during the time. Though it is argued the articles were published to protect themselves from trouble and not serious beliefs, lasting consequences for members of color within the Church occurred. The most notable example of this is the priesthood ban, which barred Black access to priesthood and temple ordinances, missions, and leadership positions within the Church. Over time, racist justifications for the ban began to permeate through Church culture and policy until the initial reason was all but forgotten by the mainstream Church.

Reeve suggests the conservative transformation of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was the price they paid for trying to save themselves from mass extermination. It was the price they paid to Evangelicals by putting out an ideology early Church members hoped they would accept. They did not. They still do not.

Political Enmeshment

Reed Smoot. Reed Smoot served five terms as a Republican U.S. Senator from 1903- 1933 after being called an Apostle in 1900. He was the first member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to maintain a national political career while serving in a prominent Church leadership calling.

After his election, the Salt Lake Tribune revealed that Church leaders were secretly practicing polygamy even after the practice had been disavowed. In 1898, B.H. Roberts ran as a Democrat for a seat in the House of Representatives and won the election but was denied his seat after discovering he still practiced polygamy. In a familiar response of outrage and reckoning, Smoot underwent a series of trials known as the Smoot Hearings, which exhaustively questioned the continuation of the practice of polygamy in Utah, as well as the doctrines, teachings, and practices of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Some opponents of Smoot claimed that polygamy was not the issue (it was made immediately clear Smoot did not practice polygamy), but rather the Mormon belief of continuing revelation and the threat it posed to national allegiance. Because so much of the population of Utah was Mormon, Utah was viewed as a theocracy. During Joseph Smith and Brigham Young’s leadership, many political cartoons and articles had painted members of the Church as violent, distrustful, ignorant, and easily manipulated by their leaders. Because of the sensationalism of Roberts and Smoot, articles, pamphlets, and cartoons returned in full force. Americans viewed Mormons as a threat to democracy and ruinous in Washington. How could Smoot simultaneously swear to sustain the United States Constitution and serve in the highest echelons of an organization that sanctioned lawbreaking? What would keep Smoot from having conflicts of interest?

For individual members of the Church, the Smoot Hearings carried more significance as a fight for acknowledging the personhood of Mormons than as the outcome of Smoot’s personal political career. In a letter to the mission president of the East States mission, Smoot wrote, “If they can expel me from the Senate of the United States, they can expel any man who claims to be Mormon.”

Once again, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints felt unsafe in a country that ironically marketed religious freedom. It had been only a little more than 80 years since the Church had been restored. There was still disorganization and inconsistency at times, but all things considered, things were going quite well. Within the state and the Church, infrastructure, agriculture, business, medicine, politics, ecclesiastics, and education were developing and refining. Smoot’s appointment to the Senate symbolized and inspired a place and a purpose for Mormons within America and Christianity. An attack on him was personal. Despite the overwhelming hostility, the vote to declare Smoot ineligible fell short, and Smoot continued to serve as a senator for thirty years. It is perhaps during this period, as Mormons identified with Smoot and personalized his victories, that politics and religion began to fuse, and the identity politics that so many American Church members adhere to slowly coalesced.

Ezra Taft Benson. Shortly after World War II, President Benson was called to serve a humanitarian mission in Europe. He witnessed first-hand the devastation and destruction of cities and nations. He blamed what he saw on totalitarian regimes and was very worried the United States would come to a similar fate if it embraced Socialism or Communism. Later, when working in politics, he saw the New Deal up close, and its policies scared him. He noticed that while the rest of the nation was receiving $1.87 federal assistance per capita, Utahns received $5. This deeply concerned him, and he felt the need to advocate for what he believed to be right.

In an exciting contrast to Smoot’s political experience, Ezra Taft Benson had a relatively smooth transition into President Eisenhower’s cabinet as Secretary of the Department of Agriculture, despite being in the Quorum of the Twelve. In response to the appointment, the American Council of Churches opposed the decision claiming that Elder Benson was a member of a “pagan religion…hostile to the Biblical evangelical Christian faith.” However, nothing more came of it, and he held the position for eight years. His political leadership was controversial at first but gained popularity over time.

Ezra Taft Benson abhorred anything that resembled Socialism, including the welfare program, big government, Social Security, Medicaid, and Medicare. He thought the civil rights movement was infiltrated by Communists. Elder Benson thought that civil rights for Black people were an honorable thing to want, but the movement was a tool for Socialists, much like how some conservatives feel about the Black Lives Matter movement. The John Birch Society wanted to nominate Elder Benson for United States president with segregationist Strom Thurmond as his vice president for the 1968 election. He asked President McKay for permission and was given the green light. After the nomination fell through, Alabama Governor and now notorious bad guy George Wallace asked Elder Benson to run with him in the presidential election as vice president. This time when Elder Benson asked President McKay, he was denied, even after Wallace called President McKay on Elder Benson’s behalf.

Personal politics aside, regarding members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and American integration, President Benson is a success story. For a traumatized people who were desperately searching for the promised blessings of keeping covenants and making sacrifices, his accomplishments seemed like their own, especially to members of the Church who remembered Smoot and Roberts's hostile treatment only fifty years prior. Remember when Mitt Romney ran for president, and regardless of political leanings, it was exciting? As a Democrat friend of a friend said, “I would never vote for Mitt, but it’s nice to see one from our own tribe doing well.” It must have been like that ten-fold with Missouri’s Mormon Extermination Order fresh in the mind of Church members, some of whom had grown up with being told first-hand accounts by their grandparents.

Having authority in both Church and state is uniquely powerful. This is perhaps why a repeat of a political and spiritual leader like President Benson has not happened since. Suspicions of a “Mormon theocracy” hysterically touted during the Smoot Hearings may have been reasonable. This is perhaps why in 2019, in a Church statement about political neutrality, General Authorities, general officers, other full-time ecclesiastical leaders, and their spouses were discouraged from participating publicly in politics. As seen with President Benson, Church and state were too easy to conflate.

After Ezra Taft Benson spoke at Brigham Young University in May 1961, Ernest L. Wilkinson, then president of BYU, wrote of the experience in his diary, “He gave a fine talk. It is apparent; however, it is very difficult for him to divorce himself from the active politics in which he has been engaged and get into his work again as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve. While I agreed with every word he said, I suspect there are some Democrats who did not, and he took one-third of his time talking on current political problems.”

In Elder Benson’s public addresses, he would often mention politics, using the Constitution as a Title of Liberty, vehemently painting Communists, Socialists, and Democrats with broad, anti-democracy strokes. He used the story of the Gadianton robbers and secret combinations as a metaphor for liberal ideas, spreading like a rot through American democracy. He often spoke of American exceptionalism, speaking about the Constitution and the greatness of the promised land— the United States. During his talks, he quoted from far-right publications, including American Opinion and The Naked Communist. One of his speeches was published in the Christian Crusade and was approved by Benson to be used in the forward of the book The Black Hammer: A Study of Black Power, Red Influence, and White Alternatives, which the Southern Poverty Law Center branded as vicious and racist.”

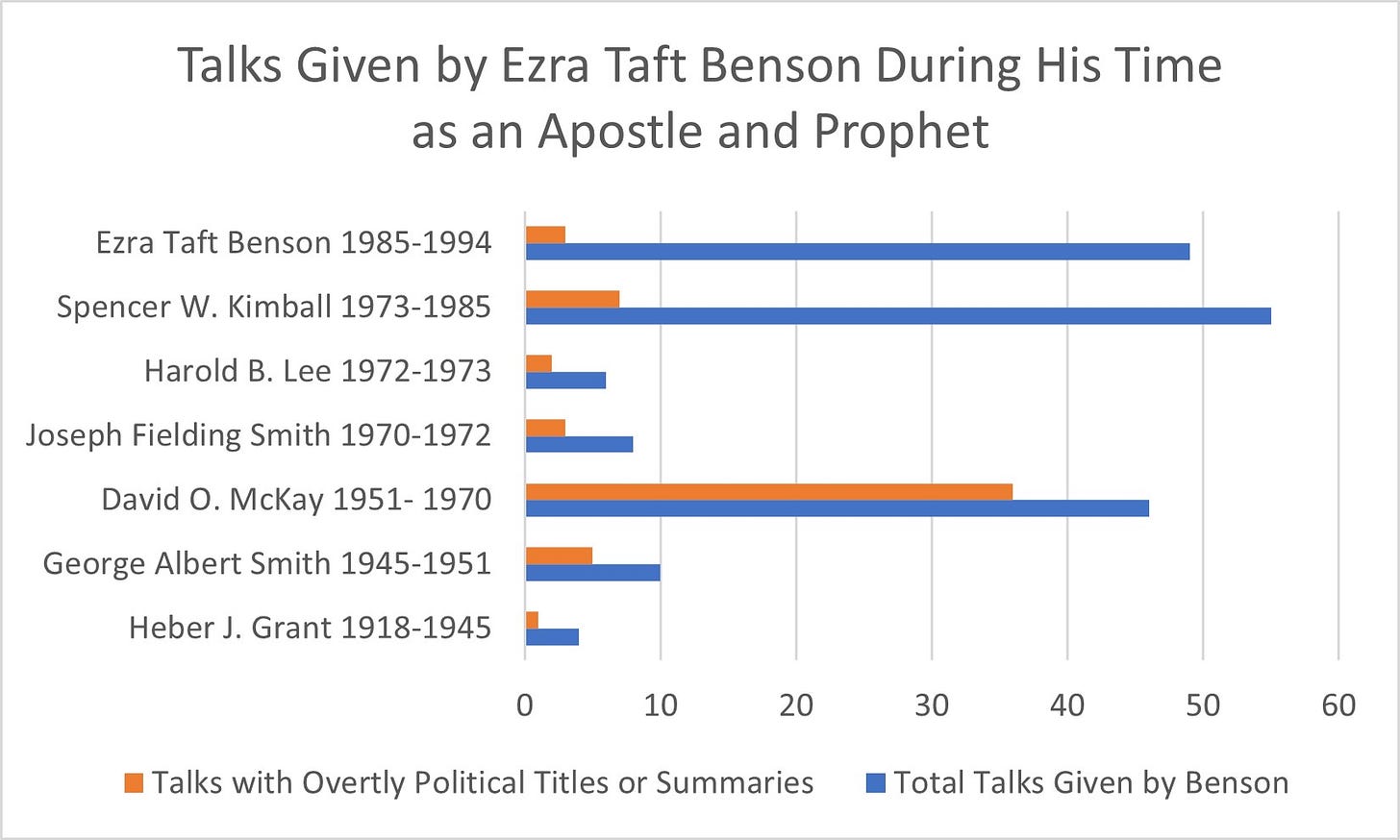

I read through an index of talks Ezra Taft Benson gave while he was a General Authority of the Church. Of the 178 talks listed, 57 were political (as far as I could tell, some I was unable to read, and others were untitled). Additional context of this data will be given later in this section and the section about Communism.

It is clear, after reading many of his talks, President Benson, among other Church leaders, is primarily responsible for the identity politics many Church members embrace today. To make this a little clearer, below are some examples of partisan views embedded in a few of his talks that shaped modern identity politics within the Church.

Moralizing politics by using the doctrine of the pre-mortal life:

“Today, the devil as a wolf in a supposedly new suit of sheep’s clothing is enticing some men, both in and out of the Church, to parrot his line by advocating planned government guaranteed security programs at the expense of our liberties. Latter-day Saints should be reminded how and why they voted as they did in heaven. If some have decided to change their vote, they should repent—throw their support on the side of freedom—and cease promoting this subversion.” – American Heritage of Freedom: A Plan of God, General Conference 1961

Either-or fallacy using Christ and Satan to paint politics as binary:

“Today, we are in a battle for the bodies and souls of man. It is a battle between two opposing systems: freedom and slavery, Christ and anti-Christ.

… So, I say with all the energy of my soul that unless we as citizens of this nation forsake our sins, political and otherwise, and return to the fundamental principles of Christianity and of constitutional government, we will lose our political liberties, our free institutions, and will stand in jeopardy before God.”—A Witness and a Warning, General Conference 1979

Condemning Socialist and Democrat policies:

“In reply to the argument that a little bit of Socialism is good so long as it doesn’t go too far, it is tempting to say that, in like fashion, just a little bit of theft or a little bit of cancer is all right, too! History proves that the growth of the welfare state is difficult to check before it comes to its full flower of dictatorship. But let us hope that this time around, the trend can be reversed. If not, then we will see the inevitability of complete Socialism, probably within our lifetime.” – The Proper Role of Government, General Conference 1968

Using the Book of Mormon to educate families against views outside of conservatism:

“Now, we have not been using the Book of Mormon as we should. Our homes are not as strong unless we are using it to bring our children to Christ. Our families may be corrupted by worldly trends and teachings unless we know how to use the book to expose and combat the falsehoods in Socialism, organic evolution, rationalism, humanism, etc. Our missionaries are not as effective unless they are “hissing forth” with it. Social, ethical, cultural, or educational converts will not survive under the heat of the day unless their taproots go down to the fulness of the gospel which the Book of Mormon contains. Our Church classes are not as spirit-filled unless we hold it up as a standard. And our nation will continue to degenerate unless we read and heed the words of the God of this land, Jesus Christ, and quit building up and upholding the secret combinations which the Book of Mormon tells us proved the downfall of both previous American civilizations.” – The Book of Mormon is the Word of God, General Conference 1975

Who’s on the Lord’s side who:

“There are some who apparently feel that the fight for freedom is separate from the gospel. They express it in several ways, but it generally boils down to this: Just live the gospel; there’s no need to get involved in trying to save freedom and the Constitution or to stop Communism.

Of course, this is dangerous reasoning because, in reality, you cannot fully live the gospel without working to save freedom and the Constitution and to stop Communism.

In the war in heaven, what would have been your reaction if someone had told you just to do what is right—there’s no need to get involved in the fight for freedom?” – Protecting Freedom—An Immediate Responsibility, General Conference 1966

Welfare and food stamps:

“Recently a letter came to my office, accompanied by an article from your Daily Universe, on the matter of BYU students taking food stamps. The query of the letter was: “What is the attitude of the Church on taking food stamps?” The Church’s view on this is well known. We stand for independence, thrift, and abolition of the dole. This was emphasized in the Saturday morning welfare meeting of General Conference. ‘The aim of the Church is to help the people to help themselves. Work is to be re-enthroned as the ruling principle of the lives of our Church membership’ (Heber J. Grant, Conference Report, October 1936, p. 3).

“When you accept food stamps, you accept an unearned handout that other working people are paying for. You do not earn food stamps or welfare payments. Every individual who accepts an unearned government gratuity is just as morally culpable as the individual who takes a handout from taxpayers’ money to pay his heat, electricity, or rent. There is no difference in principle between them. You did not come to this University to become a welfare recipient. You came here to be a light to the world, a light to society—to save society and to help to save this nation, the Lord’s base of operations in these latter days, to ameliorate man’s social conditions. You are not here to be a parasite or freeloader. The price you pay for ‘something for nothing’ may be more than you can afford. Do not rationalize your acceptance of government gratuities by saying, ‘I am a contributing taxpayer too.’ By doing this, you contribute to the problem which is leading this nation to financial insolvency.” – A Vision and a Hope for the Youth of Zion, BYU Devotional 1977

In 1990, when President Benson’s health was failing, the Church's leadership rewrote the Church welfare manual, and Gordon B. Hinckley went on record, informing the Church that being on welfare was not anti-Gospel. When called to be the prophet, President Hinckley called James E. Faust, a prominent Democrat, to the first presidency, refuting President Benson’s long-standing belief that you cannot be anything other than a small government supporting, welfare state rejecting, conservative.

Communism

While all the General Authorities were uniformly against Communism in the 1950s, the direction this opposition took was hotly disputed amongst Church leaders. President McKay, influenced by his Republican leanings and personal experience with Communism, allowed Elder Benson to speak openly (see graph in the previous section). Peppering his talks with David O. McKay's endorsements, he began relentlessly pumping the mainstream Church with right-winged views in Conference talks, devotionals, and firesides. It wasn’t out of malice or manipulation; Elder Benson truly believed in what he was saying and felt a moral imperative to use his platform to share his convictions with others. In a 1954 General Conference address, he said, “It is right politically for a man who has influence—of course, influence for good—to use it.”

Other apostles, such as Joseph Fielding Smith, Harold B. Lee, Hugh B. Brown, and N. Eldon Tanner disagreed and did not like Elder Benson’s approach. Although they did try to rebuff his ideas in their discourses and conversations with members, they did not explicitly identify the remarks they were rejecting as Elder Benson’s to avoid undermining his apostolic authority. President Hugh B. Brown, known for disagreeing with Elder Benson, walked back many of Elder Benson’s statements, but, unfortunately, it’s solely President Benson’s passion and extreme patriotism that is remembered.

In addition to being anti-Communism and anti-Socialism, Elder Benson was a strong proponent and contributor of the John Birch Society, an extremist group known for its far-right ideology, promotion of limited government, and conspiracy theories. President McKay never allowed Elder Benson to join the Society, but Elder Benson’s son, Reed, played a prominent role in the Utah chapter. Because of Elder Benson’s fears about liberal ideas being taught at BYU, he asked Harold B. Lee and President Ernest Wilkinson to hire Reed to keep a close eye on students and faculty and report any suspicious ideas. President Wilkinson declined, saying, “Neither Brother Lee nor I want espionage of that character.”

As Elder Benson promoted the ideas and publications of the John Birch Society among the brethren and the Church, other general authorities were angry. Hugh B. Brown and N. Eldon Tanner told Church members to avoid extremism and not to rush to dismiss those that disagreed with them as “Communists.” They put out fires with members local and abroad, confused and ostracized by Elder Benson’s remarks.

In January 1963, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints put out a statement in the Deseret News, distancing itself from the John Birch Society. When Joseph Fielding Smith became prophet after David O. McKay died in 1970, he forbade Elder Benson from discussing politics in his talks. In 1980, the Church put out an official statement regarding its neutrality in politics, including the declaration that the Church “Expect[s] its members to engage in the political process in an informed and civil manner, respecting the fact that members of the Church come from a variety of backgrounds and experiences and may have differences of opinion in partisan political matters.”

Perhaps President Benson’s opinions were so pervasive was because the mid-twentieth century was an era filled with fear. The fear of Communism caused Church members to cling to the rod and focus on it so much, they forgot about getting to the tree. They forgot the Church was worldwide. They forgot the body of Christ contains many different parts, including differing political ideologies. Elder Benson’s quote, “No true Latter-day Saint can be a Socialist or Communist,” disaffected not just members in Communist blocs, but Socialists in the UK, Canada, and Scandinavia who often turned to their local leadership after Elder Benson’s talks and asked, “Do we belong in this church? Does my political party not align with the Gospel of Jesus Christ?” In part two of this article, I will address how these are the wrong questions.

Conclusion

In closing, I want to show another graph that shows the same data in the previous graph in a different way.

The concentration of the political talks is interesting. One thing to note is that after the death of President McKay, President Joseph Fielding Smith forbade Elder Benson from teaching his political opinions over the pulpit. As he became more senior within the Quorum, his explicit political fervor subsided. His discourses became more globally minded, focusing on problems within the human condition, missionary work, the Book of Mormon, and Jesus Christ.

The reliability of Church leadership is taught to members of the Church at a young age, promising that apostles and prophets will not lead us astray. How does that fit in with the knowledge that prophets are also fallible? Is it possible to disentangle President Benson’s politics from his public addresses, rejecting one while concurrently embracing the other?

As I have researched this topic, I have found it to be faith promoting. Answering the questions above takes a considerable amount of thought and prayer. It is not easy, but the outcome has helped me become a more intentional follower in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The time and effort it takes to deconstruct the identity politics that have plagued the Church until this moment are daunting. I understand why so many do not do it. But I believe that as we create space for different ideas and political leanings within the Church while embracing the Gospel of Christ, we will find a new identity that will emerge—becoming part of the body of Christ. As we do this, I imagine, we will be surprised by whom we find there.