This remembrance was originally published in the Mormon History Association newsletter.

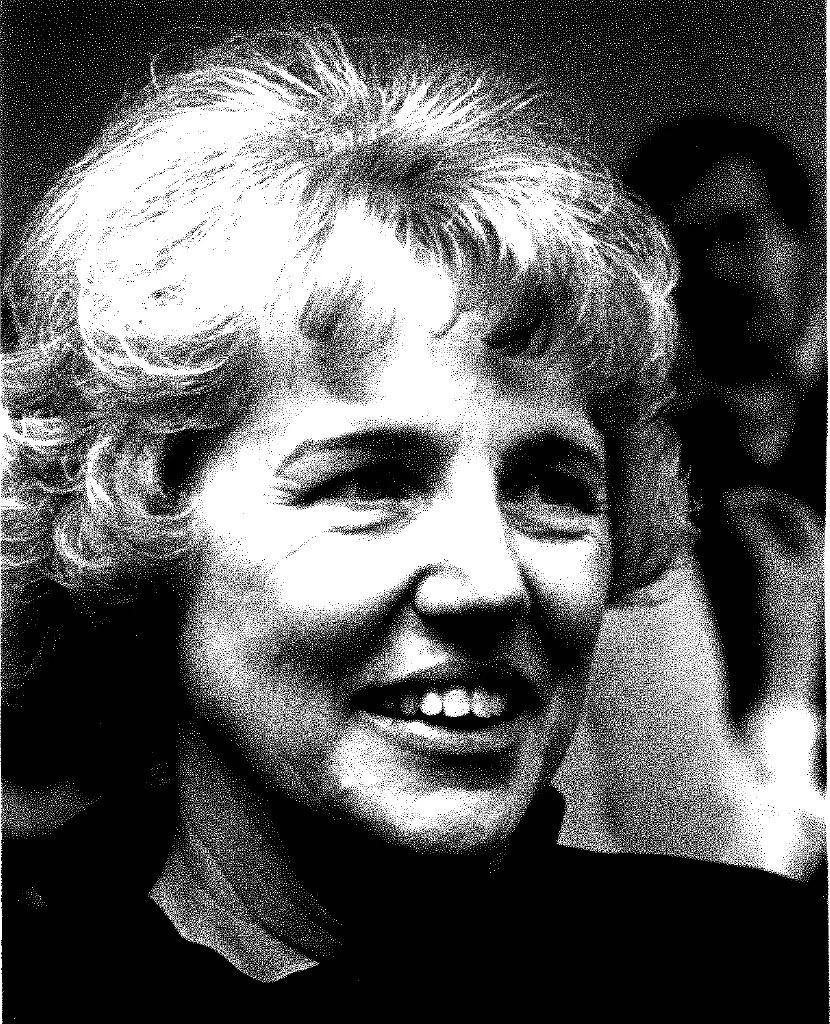

Jan Shipps has died. Her last days ended peacefully in the dark, wee hours of April 14, 2025. Her death marks the passing of a great force.

Many readers of this publication are apt to know Shipps as a much-loved and transformative student of Mormon history. Her self-understanding, however, centered on four preoccupations: her family, her teaching and study at Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis (IUPUI), her Methodist-inflected Christian faith, and the Mormon people and what she deemed their sharply distinctive and complex restoration, along with the scholars who studied them and it.

Her commitments to her family and hardscrabble origins were profound and fond. JoAnn Bartlett was born in rural Alabama (1929, as the stock market crashed), her early home a shade above ramshackle. Her father was a one-horse coal miner “who could fix anything.” She remembered her sister as “the pretty one” and her mother as deeply intelligent and the largest influence in her young life. Without family precedent, Jan managed to enter Alabama College, though, sadly, at a time when her family’s money ran out. After a fifteen-year pause that included marriage (Anthony Shipps), motherhood (Stephen), tending displaced children, and playing piano in bars to help make ends meet, she completed her college degree at Utah State University, where Tony had accepted a librarian’s post.

There Jan compressed two years of courses, mostly in history, into a single year. “Most of those courses were about Mormonism in some fashion, regardless of what the catalogue said.” In 1965, she was awarded a PhD in history from the University of Colorado, writing what she would later call a “not very great” dissertation on the Saints and politics. Women with PhDs were not common in 1965. It would take the better part of a decade before she secured a place in the academy and she found herself a lonely female presence when she began presenting at national conventions of the guild.

The culture shock she had encountered in Logan was eventually supplanted by a fascinated, loving, prescient, and permanent curiosity about the Latter-day Saints. Coupled with a rare intelligence masked by a folksy Southern-Midwestern-far Western charm, Jan forged from this curiosity an uncommon career marked by uncommon influence—among scholars, among church members and their leaders, and among the press and therefore the wider public. In time she came to know the Latter-day Saints (and the Mormon movement more broadly) better than any previous outside observer and in some ways better than most insiders too. She became “an insider-outsider in Zion,” affording her unusual perspectives and access to sources, including officials in the highest echelons of the church (and in other churches claiming allegiance to the teachings of Joseph Smith).

This status garnered her diverse titles. “That celebrated Mormon-watcher” and “that beloved Gentile” is how apostles have publicly referred to her. Others have deemed Shipps “the twentieth century's Thomas L. Kane”—so useful has her fairness, good will, and penetrating insight seemed to the Saints. Less reverently, she has been called “the Jane Goodall of Mormon studies” and even “the Mormon Mascot.” One critic, who thought she was too gentle on her subjects, feared that she had either gone soft or gone native. Prior to her waning years in the last decade of her life, authorities, reporters, and scholars invoked her presence, insight, and prestige so often that in September 2003 Mark Parades, speaking in Seattle to the Religion Newswriters Association, recalled that when he was a student there, Shipps had become “the pinup girl of BYU.”

In 1980, Leonard Arrington affectionately crowned the genial and entrepreneurial Shipps, who had become the first woman and first “non-Mormon” president of the Mormon History Association, “the Den Mother of Mormon History”—a role in which, sans gender, she came to parallel and then to succeed Arrington: helping to shape, shepherd, and broker the field of Mormon history and, because of her individual scholarship, the wider incipient field of Mormon studies as well. Part of her genius and her influence derived from capacities that complemented her scholarship: her gregarious ways, her mentoring care toward younger scholars, and her trilingual mastery of the necessary vernaculars: academese, mediaspeak, and Mormonish. Faithful Saints, and the scholars and reporters who study and cover them, found in Shipps a personable, generous, competent and, above all, comprehensible mediator.

Richard Bushman famously assessed Jan’s first book, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition (1985), as perhaps “the most brilliant book ever written on Mormonism, in the sense of shedding new light on virtually every aspect of Mormon history and in offering a perspective that both Mormons and others can accept.” The book was also a methodological breakthrough, whose author implanted her (self-taught) methods of religious studies into her historical examination of the Latter-day Saints. In doing so Shipps became the movement’s chief theorist. And in becoming its theorist, her methods did more than render the Latter-day Saints a worthy subject of study in the wider academy. They also became an influential model for studying religion itself in the academy, at least in the United States.

In addition to all that she accomplished professionally, Jan Shipps could cook. And of all that she cooked, her cheesy Alabama grits (often more cheese than grits) were the best, rendered in the kitchen of the Shipps’s serene and cozy Balmy Gilead Farm in the woods outside Bloomington.

Despite all these glories, even a report so briefly sketched as this one should retain a measure of balance. In homage to this principle, let us admit by postscript: Dr. Shipps was a genuinely awful driver. Should her friends find themselves on a journey with Jan while in her car—to an MHA conference perhaps—it was generally best if they rather than she commanded the steering wheel. When Jan drove, only attendant road angels, fretting and fussing above her, prevented inner-city calamity. But then grace has often been amazing.