The Saga of '78

Matt Harris brings the story of the priesthood and temple ban into the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries

Honesty is the only way to heal faith communities from the devastating effects of racism, and if people of goodwill can learn from the Latter-day Saint experience, it might prompt them to excavate their own racial assumptions, wipe them clean of apologetics and rationalizations, and begin anew.

Matt Harris, Second-Class Saints, xv

Late last year, the Utah Monthly had the chance to sit down with Matt Harris, a professor of history at Colorado State University Pueblo and a scholar of twentieth-century Mormonism. In December, we published the first half of that conversation, available here. In the second half of our conversation, included below, we discuss Harris’s most recent book, Second-Class Saints: Black Mormons and the Struggle for Racial Equality, which came out in July 2024. Our discussion, which has been edited for length and clarity, touches on President Spencer W. Kimball’s role in reversing the priesthood and temple ban, ongoing efforts to heal the traumas caused by decades of church-sanctioned racism, the part that Harris’s book might play in those efforts, and forgotten twentieth-century Latter-day Saints whose stories merit retelling.

What two or three new findings does Second-Class Saints bring to the history of the priesthood and temple ban?

I’m plowing new ground everywhere, because we’ve never had a detailed account of the ban during the twenty and twenty-first centuries. We’ve got some wonderful scholarship on the nineteenth century, but not on the twentieth and twenty-first. It’s not because scholars haven’t had an interest, it’s simply because the materials to write such a story have never been available. So I got access to these restricted collections in several different archives.

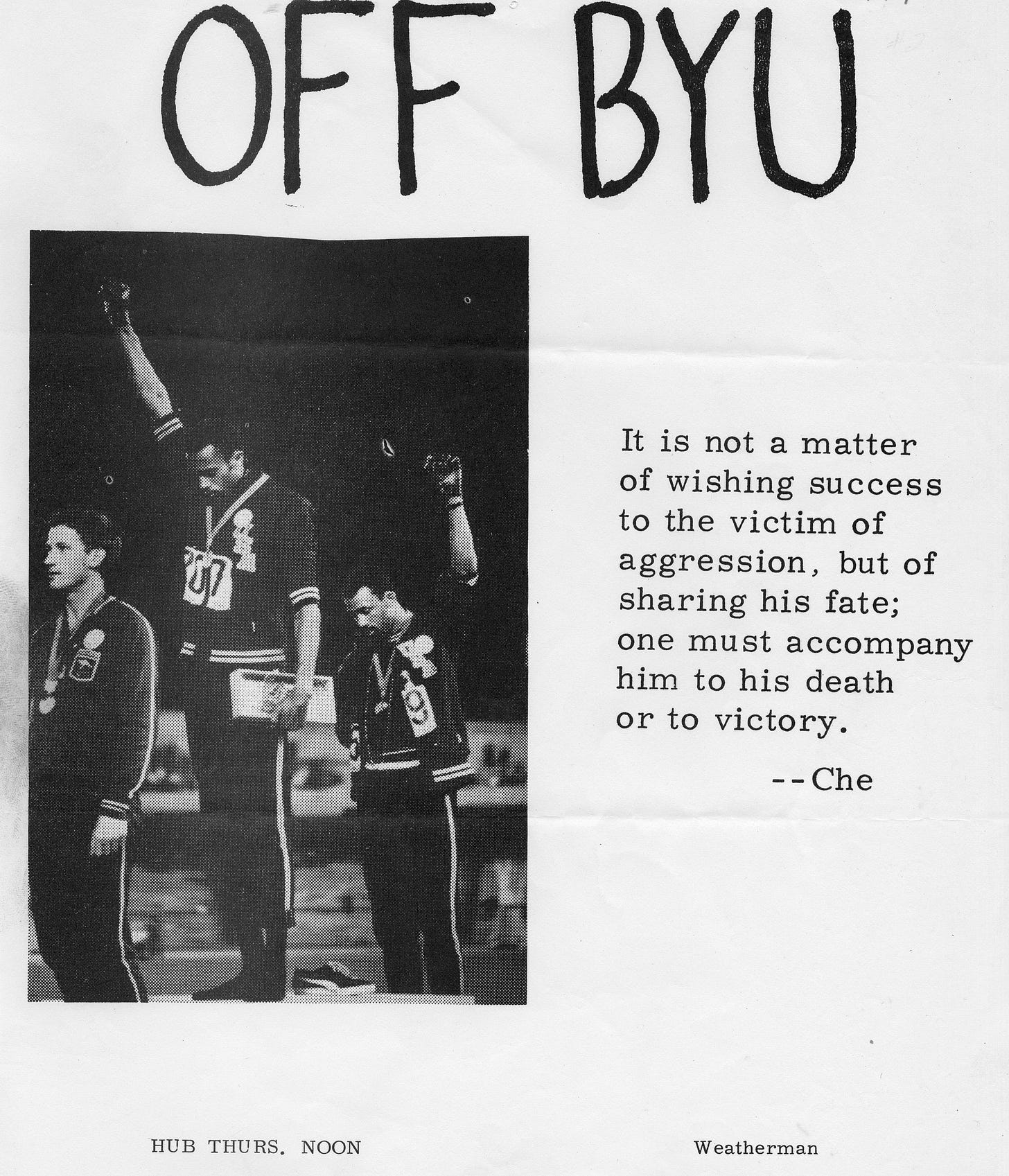

But in terms of a rapid-fire response to your question, we’ve never had an extended look at how Latter-day Saints crossed the color line to pass as white, particularly in South Africa. We’ve never had a look at how the federal government was going to shut down BYU for civil rights violations. We’ve never had a detailed and intricate look at how President Kimball lifted the ban and how he had holdouts, including Mark Peterson, Delbert Stapley, and Ezra Benson. We’ve never had a detailed look at how he won over Elder McConkie. Most people think that McConkie would be the last person to lift the ban, given his views, but he was actually one of the first to come on board. We’ve never had a look at external things pressuring the brethren, like the Internal Revenue Service.

When I came to your book talk in Provo, I remember being particularly struck by what you said about Spencer Kimball. I think you said that church members have this image of Spencer Kimball praying for a revelation to overturn the priesthood man, but you said that what he was really praying for was to get his fellow apostles on board. Could you talk about that?

Can I say something controversial? I’m going to say it anyway. So Saints IV: Sounded in Every Ear, which just came out, is very traditional in its depiction of the priesthood revelation. I’m going to give a crude characterization, but it goes something like this. President Kimball wanted to lift the ban, and felt a little uneasy about it, and then one day he was praying on June 1, 1978, and God told him, “Hey, lift the ban.” And, I mean, that's just not supported by the evidence. So what I argue in my book is that revelation is a process. So the church president gets inspired to do something, and then he broaches it with his colleagues in church leadership, and they debate, they discuss, and hash it out. And then they vote. And once it becomes unanimous, the president of the church then stands and says, “I feel to say that this is a revelation.”

And that’s so jarring to the way most people are conditioned to think about revelation. For many, the idea is that God just tells you something and boom, there it goes. But when it comes to institutional issues like doctrines and policies, and especially one as important as the priesthood and temple ban, it required unanimity among the top fifteen leaders of the church, the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. And so my book looks at how President Kimball convinced the apostles I categorize as “hardliners” that it was time to lift the ban. You couldn’t globalize the church if you couldn’t go into majority black countries. And so that's the revelation. It didn’t happen on June 1. It happened in the weeks preceding June 1. But Saints IV gives [the impression] that somehow this was passive, that the revelation just came and they all felt it.

I’m not saying there wasn’t a great spiritual experience in the temple that day, because I think that there was. I think that there’s strong evidence for that. But we have to be careful what we’re talking about. The spiritual experience wasn’t, “Oh, I feel like we’re going to lift the ban today.” That’s not it at all. It was that the last holdouts recognized that the church needed to go forward and they felt that they were convinced that day. That was the revelation.

And they had to be convinced. Elder Benson did not even want to talk about the priesthood and temple ban being lifted on June 1. In fact, he voted that they table the discussion. And that’s when Elder McConkie and Elder Packer and some others came to President Kimball’s defense and talked Elder Benson into it. And in fairness to Benson, I think he felt this is what God wanted him to do. And the rest of the brethren had already come around to it, at least the ones who were there on June 1.

The ones who didn’t come around to it were Delbert Stapley, who was in the hospital, gravely ill, and Mark Petersen, who was in Ecuador on a church assignment. And that was not by coincidence. They could not win Elder Petersen over, and so they sent him to Ecuador to get him out of the country. So institutional revelation is a process, not an event. That’s what I argue in my book, and I think that’s been hard for some people to hear, but for whatever it’s worth, Hugh Brown taught that revelation is a process, Neal Maxwell taught that revelation is a process, and just recently, I think Elder Christofferson talked about revelation as a process.

For the chapters you spent talking about Spencer Kimball’s presidency, what sources and collections were you looking at that allowed you to flesh out that story?

The gold standard: diaries, meeting minutes from the First Presidency, Kimball’s private letters and papers—I’m the only scholar who’s ever seen these. And the diaries have been posted online, [but they have been] heavily redacted. Frankly, the diaries are not that helpful both because they redacted a lot of stuff and also because on June 1, 1978, the day of the revelation, President Kimball didn’t really talk about it much. He was likely exhausted, and just didn’t. It wasn’t a good journal day for him. And then the following week, on June 8, there’s a little bit more in his diary that’s really helpful, and I quote all this in my book. But the truth is, most of the stuff that goes on that sort of gives you a look at how he’s feeling and thinking occurs in private letters. And you can see a lot of those letters quoted in my book.

In some of the later chapters in the book, you talk about the legacy of the priesthood and temple ban, about how the folk theology surrounding the ban persists and how it hasn’t been repudiated as publicly or as forcefully as it maybe should have been. So that being said, where you think we are at now with the priesthood and temple ban?

So in 2013 the church posted on its website a gospel topics essay on race and the priesthood. And the essay just bulldozes a gaping hole in the theological infrastructure of black priesthood denial. It’s an incredible document. It’s got problems too. There are some things that are not in that document, but I want to praise it for what it is. It repudiates specific anti-Black teachings that the church had never repudiated before, like the myths that Black skin is a sign of divine curse, Black people were less valiant in the pre-existence, or that interracial marriage is a sin. I mean all of that is in there, and that’s really important, and I’m really happy the church did this, because it gives Latter-day Saints an artifact that they can hoist when somebody says something racist at church; they can say, “you know, that’s not what we teach anymore.” So that's important.

The lack of an official apology is extremely important. And I know that at least for the folks in the Black community with whom I have contact, I mean, they’re begging for an apology. They want one, and the church has refused to give one because they feel like it would undermine their prophetic authority if they apologized for a key doctrine that was in place for 126 years. And of course, the slippery slope would be if they were wrong about this doctrine, what other doctrines are they wrong about, particularly LBGTQ issues? So that, in my opinion, is what is holding this up: the fear that an apology would undermine prophetic authority.

But it is no small thing that President Nelson and some of his associates have formed partnerships with the NAACP. I mean, that’s huge, and giving money to not just the NAACP to fight racial injustice, but also to Morehouse College, an HBCU. And, you know, somebody once said that that’s the church’s way of apologizing. And I can be persuaded by that, although an official apology would go a long way in trying to heal some of these Black and Brown Latter-day Saints who have suffered immensely from the church’s race teachings.

Your book is an academic work, it’s not pastoral, but I’m curious, do you see it as having some sort of role in healing the legacy of both the priesthood and temple ban and of white supremacist thinking within the church?

You really hit it nicely, it’s not a pastoral book. I’m a scholar and historian and the book is history and culture and theology and all of this legal stuff all rolled into one. So I didn’t set out to write something that would be pastoral, but I did want to write something that could be healing for Black Latter-day Saints. What’s interesting about that is that I’ve heard from a lot of Black Latter-day Saints who thank me because they found tremendous healing from reading my book, but I’ve also found people for whom this history is jarring—coming to terms with the racism and how deep it was in the church for so many years has been a hard pill to swallow for some people. But to answer your question, I’ve heard from a lot of Black Latter-day Saints who have found healing in the book and that really makes me happy.

From all of your research into twentieth-century church history, are there exemplary figures from the church’s past who you wish were more well-known?

Yes. Marion Hanks is one of them. He’s doing all kinds of things: he’s promoting church work with refugee camps, he’s promoting civil rights, he’s talking about the poor and the needy and what the church and the government can do to help them. I mean this is not something that his colleagues are talking about. So his liberal voice is just a breath of fresh air. Hugh B. Brown would be another one. I’m writing a biography of Brown and wow, what a remarkable man and remarkable life; he was the mentor to Hanks if that tells you anything. So those two for sure.

Paul Dunn is another one. He’s controversial for some of the things he did later in life, but his earlier ministry—I mean some of his sermons and the way that he managed people—is worthy of emulation. People outside of church leadership I think deserve bigger praise. Lowell Bennion is another one. Not a church leader but had the confidence of some of the church leaders like Brown and David O. McKay. He taught institute at the University of Utah from the 1930s until he was fired in 1962. Talk about a great Christian man. He was always talking about how to apply gospel principles to real-life problems, so he’s giving his own version of the social gospel in a Mormon setting.

Another one would be Sterling McMurrin. McMurrin is controversial because he was a non-believing philosopher at the University of Utah, but he maintained close friendships with Brown and McKay and just had an immense amount of integrity. He wasn’t afraid to criticize the church when the church leaders did something stupid, but he also defended the church when he thought that people were unfairly criticizing it.

One last one I’ll mention is Obert C. Tanner, who’s known in Utah today for O.C. Tanner Jewelers. Tanner taught alongside Sterling McMurrin in the University of Utah’s philosophy department for a number of years, and he also authored many of the church’s manuals in the 1930s and 1940s, even though he was slipping away from belief. He didn’t fully believe in the church’s truth claims yet he’s writing their manuals. Frankly, they read like Protestant tracts and would never pass correlation today, but since he was close friends with some of the brethren and was a good writer and a good thinker, they entrusted him to do that.

Matt Harris has generously offered to answer any questions posted in the comments section of this interview. Out of respect for Harris’s time, please try to make questions brief and straightforward.

My husband and I both thoroughly enjoyed your book—it’s truly remarkable.

In the interview, you mentioned that the book was made possible by your access to materials that have never been available to scholars before. Does this signal a broader shift in the availability of restricted LDS historical documents to researchers, or is it more likely an exceptional case due to your unique relationship with those holding the materials? I’m curious about how you navigated the process of requesting access to such sensitive resources.