Walks in the Confusion Range

I, a non-native, non-placed person, have somehow found connection to natives, to places that slowly, perhaps, are becoming my own

I.

In late summer I walked across a long meadow of sage and drying wildflowers spread out northward of King Top, the high point of the Confusion Range in Millard County. The range breathed silence, especially here, at 8,000 feet, near the heart of the wilderness study area. The air was tangibly clear, the pinyon needles imbued with striking hues of blue green. The juniper scales showed off an equally potent yellow green, all around the sage meadow, with shin-high, and then knee-high sage, Artemisia; lover of the west.

I weaved around bushes, mostly sage, occasionally other forbs, that are part and parcel of the gray green of the desert, careful not to step on any plants. The blue sky burned above, open, vast, empty, bare, waiting for some heavenly interruption. No interruption. I moved on, catching the tones of a tiny blue gray gnatcatcher somewhere unseen in the wall of trees ahead, a long way off.

I rounded a corner and stepped across a low wash, dry, with occasional rocky shoulders breaking a monotony of sage. Then, up and around into a new valley which pointed southeastward, toward King Top. More sage, forbs, gravelly limestone soil.

Suddenly, something behind me stirred. I turned, nothing. Maybe a breeze? But the air was still. Maybe a rabbit, but I hadn’t seen any for a long while. I faced King Top and walked on. A minute later, it happened again. Somewhere behind me, I could feel, was something, or someone. The meandering path I took was not mine alone. In snaking lines between the sage, I walked, but not alone.

Slowly, my apprehensiveness subsided, replaced with a wonder that settled into comfort, even joy. The fibers of my being stood out, like hair brushed vigorously with a balloon. The flats of sage were not only mine, had never been only mine. I walked in utter companionship.

Reaching down, I picked up a tiny chip of obsidian, not unusual in these parts. I knew that Native Americans once walked these meadows, these ridges, these canyons. But now, holding the gleaming round of black stone in my palm, the words came, in a whisper of implausible connection:

“I am the one who chipped this chip; I am the one who walked these walks, I am he who walks with you.”

II.

Little is known of the native inhabitants of the Confusion Range. Overlooked (perhaps unintentionally) by archeologists, the range sits squarely in the dry bareness of western Utah. No perennial streams, no ponds, no springs—no water. In an early-twentieth-century survey of Native American tribes of the Intermountain West, the anthropologist Julian Seward offers a map with this descriptive label spread out across western Utah:

“Few Inhabitants – Mixed Ute and Gosiute”

Apparently, the absence of water and timber, along with the scarcity of game, kept both the Goshute (Gosiute) to the west and the Ute to the east from establishing permanent settlements in the region. Seward is brief in his description of territory used by the Pahvant (Sevier Desert) Utes, saying “they ranged the deserts surrounding Sevier Lake west of the Wasatch Mountains nearly to the Nevada border, where they were somewhat mixed with the Gosiute”.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Utes likely visited the Confusion Range, maybe to collect pine nuts from Pinus monophylla, the single leaf pinyon. Seeds, or “nuts,” from this species proved essential for the survival of both Utes and Goshute. Native Americans spent falls harvesting the nuts, which they subsisted on through the cold, dark winters of the Great Basin.

All this information concerns the most recent Native cultures, those who encountered European explorers and pioneers during the first decades of settlement, as the West underwent a trial of domestication. Prior to that time, Native American use of the region around the Confusion Range fades into obscurity, punctuated only irregularly with tidbits of tantalizing detail.

One such instance is the Hell ‘n Moriah Colvis site, located along highway 6 and 50, the main paved artery that crosses Millard County from east to west. The site is in Tule Valley, at the northeastern base of the Confusion Range, some 10 miles northeast of King Top. The excavation of around 150 stone artifacts at the site revealed that the area was occupied by nomadic Clovis people sometime between 14,000 and 10,000 years before present, when waters from Tule Valley Lake, an isolated arm of shrinking Lake Bonneville, were nearby. These provided marshy habitat for animals hunted by the paleo-people, which included mastodons and other mega-fauna. Later, Clovis people may have gathered at the site to prepare animals for consumption. The time is so distant, though, and the people so remote, so foreign. At some point, documentation slips into speculation, and we are left with whispers of incoherent blowing alkali dust.

In the Tule Valley of today, below towering cliffs of the Confusion Range to the west, and high crags of the House Range to the east, it is hard to imagine a lush valley of water around which mastodons and cheetahs chased pronghorn “antelope.” But these were all here, once, along with people. I do not know their language. I cannot begin to imagine what beliefs they may have had. But I do know the places they lived and wandered in, and this brings me a strange sense of comfort.

III.

A more recent (and non-native) inhabitant of the Confusion Range was Jack Watson, a sheep herder and manager of the post office at Ibex during the early twentieth century. Ibex sits near a maze of Ordovician quartzite bedrock at the south end of Blind Valley, southeast of King Top. Jack chose the site because bowls in the quartzite hold rainwater nearly year-round, which was a good thing for his thirsty sheep.

Jack often kept his sheep in “The Barn,” a long, steep-sided basin in the hills north of Ibex that served as a natural holding place for the animals. Water in this little valley drains first southward, and then eastward, where it makes its way through a narrow canyon to Tule Valley below. At the head of the canyon is “The Jumpoff,” where Jack sometimes went. As noted by Michael R. Kelsey, there are petroglyphs of bighorn sheep at The Jumpoff.

On a cold, foggy day in early December, I drove out to the Confusion Range in misty pre-dawn darkness. My aim was to explore the rocky hills around The Barn and maybe see the petroglyphs, too. I started out in dense fog and dark, my headlamp casting a soupy beam ahead of me on a hillside of rough limestone ledges. My boots crunched over hard snow, around Ephedra and sage, and grasses. After an hour or so, I knew the sun had risen, its presence known, yet obscured by omnipresent, stagnant fog.

Wading through the white and gray, I rounded several rocky hills of increasing height. Eventually I began a scramble, up and around a couple ledges, and then a steep slope. At the top, all at once, I rose above the sea of fog and clouds, squinting my eyes in a sudden oblivion of dazzling winter sun and snow. The curtain of fog lay draped over the desert below, all the way to Delta, some 60 miles eastward, and beyond.

At my immediate south, The Barn layed cloaked in billows of soft gray. Jack’s natural corral, place of sheep and Native Americans. And petroglyphs.

The day was a wild one: up and down rocky peaks, scrambling, route-finding, slipping, sliding on snow, soaked feet. The whole deal of winter hiking. And, in and out of fog, periodically popping above the clouds, which seemed to want to stick around all day, only to fall back down into cold oblivion, if only for a time.

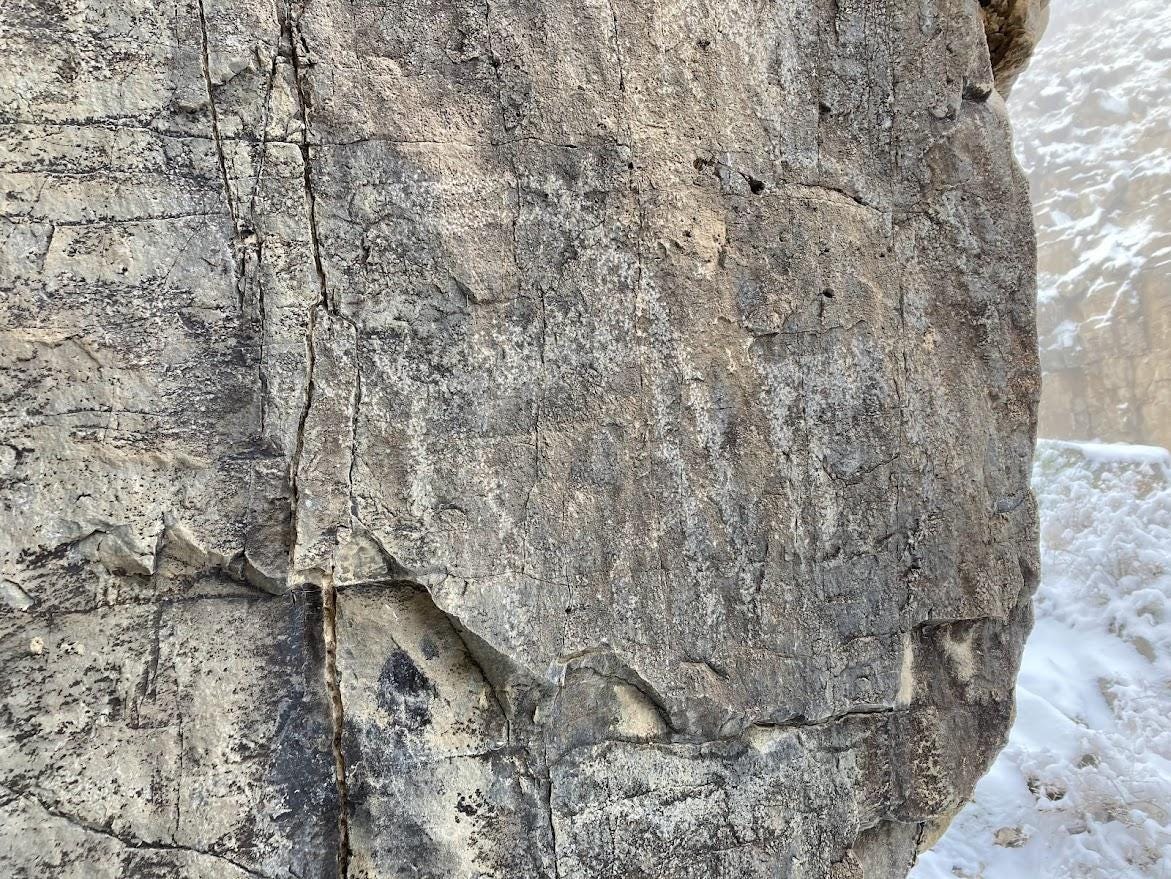

Near the day’s end, I at last came to the narrow canyon at the bottom of The Barn: The Jumpoff. All was misty-white, the sun having dropped behind hidden ridges of limestone to the west. Following Kelsey’s directions, I “veer[ed] south to get around the dropoff”, where, according to Kelsey, “on the cliff at eye level and facing east, will be a faint petroglyph of big horn sheep”. Rounding edge of rock and standing on a narrow ledge above the canyon bottom some 20 vertical feet below me, I fumbled for handholds on the rock wall to steady myself. Then, another step or two, and I surveyed the face of stone, and there, true to description, were two bighorn sheep.

The fog was thick. Night was gathering quickly around. The canyon walls arched upward to unseen craggy heights. All was calm, just me and the two sheep, chipped, ancient outlines. To my untrained eyes, the sheep appeared different than others I’d seen. Their horns, maybe, were a little longer, or arched back a little farther. The images, overall, were worn enough to make the animals imperceptible to a hurried eye. But this was not mine, and I stood, and stood, and stood, in the cold fog, thinking of sheep.

Were they placed there by the Clovis? Or the Utes? The Goshute? Or, maybe, by my unseen companion from King Top. All seemed plausible; none seemed likely. I gathered in the feeling of that place, holding out my arms in an embrace of place and people. And then, not wanting to overstay my welcome, I turned from the limestone wall to start down the narrow canyon. The remainder of the hike was a long, foggy walk in darkness through Tule Valley and finally to my old Ford Ranger, a riveted frame of steel, modern appliance of the white man, European, conqueror.

IV.

The Confusion Range pulls me in, and I—a foreigner, invader—respond, and walk there, again and again. I, a non-native, non-placed person, have somehow found connection to natives, to places that slowly, perhaps, are becoming my own. But can I “own” the desert? Hinting at such a thing seems preposterous. But am I more or less than the “natives”? And who, in the end, is native?

These questions lead nowhere. Or somewhere—I am not sure. But, laying them aside, I walk into an embrace of people who become more a part of me each time I return to the range. I hope they feel my reach as I do theirs.

A poetic journey of a magical serendipity in the vastness of the western desert. Such a fascinating read! Give us more, Type! John Crook

Great word choice and description of the land and those who inhabited the area. I was hoping to see the picture of the big horned sheep. 🐑