“The real problem of humanity is the following: We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.”

Edward O. Wilson

Every so often a book title swaggers in like it owns the intellectual block. Think A Short History of Nearly Everything by Bill Bryson or The Dawn of Everything by Graeber and Wengrow. And now, The Invention of Good and Evil: A World History of Morality. These aren’t titles that hedge their bets. They’re bold. Brash, even. And they dare you to ask: Just what kind of person would write this kind of book?

If your guess is “a grizzled Oxford don with four decades of leather elbow patches and a shelf of unread monographs,” you’d be wrong. If you guessed “a young German philosopher with a taste for moral psychology and a remarkably high tolerance for conceptual risk,” bingo. Enter Hanno Sauer.

I tend to be drawn to these bold, sweeping books. They have gravitas. Unlike your typical academic volume groveling at the altar of nuance, these books try to say something—to shift the axis of your understanding, not just qualify it to death.

Admittedly, given the title, I braced for the usual screed about morality being a cultural illusion—one of those breezy “it’s all relative” takes that let dinner party guests feel edgy without requiring them to think too hard. But that’s not what Sauer delivers. Instead, he offers a sweeping, evolutionary, and deeply ironic account of morality that somehow manages to lampoon both woke virtue pageantry and reactionary nostalgia in the same breath, all while tracing humanity’s awkward crawl from tribal murder apes to moral universalists who cancel each other over tweets.

At the heart of the book is a deceptively simple premise: morality evolved because it helps us cooperate. Not in a feel-good kumbaya way, but in a very real, survival-of-the-least-stabby way. As Sauer puts it, “Our morality is a psychosocial mechanism that makes cooperation possible.” And cooperation, it turns out, is not the default human mode. It had to be painfully invented.

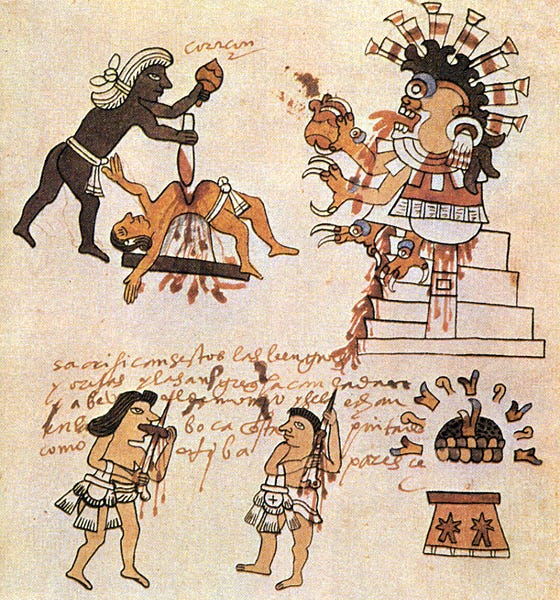

Sauer reminds us that for most of human history, we’ve been deeply suspicious of outsiders. “Inwardly, our ancestors were family-centric pacifists, but outwardly, they were gangs of murderers and plunderers.” Survival meant sticking with a few dozen kin and treating everyone else like a potential threat. “The most likely assumption right now,” he writes, “is that we domesticated ourselves by simply killing the most aggressive and violent members of our groups.” Technological advances helped: “The taming of humanity was facilitated not least by technical achievements that made it easier and safer to murder each other”—like throwing spears from a comfortable distance.

Over time, the threat of execution didn’t just keep people in line—it rewired us, carving submission into our DNA and producing, as Sauer dryly notes, “the most compliant primate of all time.” Thus was born morality, enforced through gossip, punishment, and the occasional well-aimed projectile—just enough to build cities, economies, and eventually HR departments.

This shift didn’t just make us cooperative. It made us weird. In the larger animal kingdom, humans are pathologically social. We’re hypersocial—a term Sauer uses to describe our freakish tendency to form vast, anonymous networks of trust, belief, and obligation with people we’ve never met and will never meet. Most animals deal with strangers by fleeing or fighting. We form book clubs. The paradox is that this kind of large-scale cooperation, which defines everything from legal systems to international aid, is evolutionarily unnatural—and yet, it’s the cornerstone of civilization. Morality, in Sauer’s telling, is the social lubricant that keeps the unnatural machinery running.

But this book is no triumphalist narrative. Sauer draws from biology, anthropology, and evolutionary game theory, with detours through Nietzsche, Bentham, and Foucault (who predictably rolls his eyes at our moral “progress” and whispers discipline through a jailhouse peephole). Robert Axelrod and the famed tit-for-tat experiment make an appearance, proving that even cooperation works better when it's conditional and slightly petty.

And then there's John Haldane's delightfully grim summation of kin-based altruism: “Would I give my life to save my brother? No, but I would gladly lay down my life for two brothers or eight cousins” (see here for an explanation). If you’ve ever wanted evolutionary ethics explained via back-of-napkin math and dry British humor, this is your book.

One of the book’s most potent critiques, in my view, concerns our modern instinct to scorn past societies as irredeemably barbaric. Sauer warns that this often reflects more about who recorded history than how people actually lived. What we mistake for cultural consensus is frequently just the ideological whims of a small, powerful elite—elites who had both the quills and the cruelty to frame their preferences as inevitabilities. When we take their word as gospel, we’re not honoring cultural diversity; we’re just echoing the voices of the already-powerful and erasing everyone else all over again.

But the book isn’t content to stop with prehistoric Darwinian group selection and cousin calculus. It marches all the way down to the present day, taking a lengthy detour to admire the crown jewel of social science acronyms: WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic). As Sauer explains, WEIRD societies have moral psychologies that are historically anomalous—favoring individualism, impersonal prosociality, and guilt over shame. In other words, WEIRD people are statistically more likely to donate to a GoFundMe for a stranger’s dog surgery than help their own cousin move. (But they’ll feel really bad about it.)

The WEIRD-ness discussion is one of the book’s most valuable offerings, not just for its anthropological insight but for how it gently skewers the idea that modern Western morality is some universal moral endgame. Sauer shows how even our moral introspection—our desire to critique Western power structures and question our own assumptions—is itself a profoundly WEIRD impulse. We’re the only civilization that doubts its own values with this much vigor and still expects a standing ovation.

By the end, The Invention of Good and Evil reads less like a moral treatise and more like a very erudite (but hurried) autopsy of moral development—performed by someone who likes the patient but isn’t afraid to point out that it had some really weird habits. It’s at once sweeping and self-aware, critical but not cynical, and deeply committed to understanding how humanity got so good at being sort-of decent to strangers.

So what are we left with? A sweeping, sardonic, and surprisingly heartfelt story of how humans clawed their way toward cooperation—not out of goodness, but necessity. The Invention of Good and Evil won’t give you moral clarity, but it will leave you with a much richer sense of just how contingent and hard-won our moral instincts really are.

And if you’re looking for ideas to sprinkle into your next mocktail party discussion (Hamilton’s Rule, the domestication syndrome, Bentham’s panopticon, Zahavi’s handicap principle, and the fragile epistemic networks of trust that keep us from completely losing our minds online) this book is basically your cheat sheet.

But let’s not pretend it’s perfect. For a book with this much scope and swagger, The Invention of Good and Evil is suspiciously slim. Clocking in at just over 350 pages (with generous white space), it sometimes feels like a greatest-hits album where half the tracks were cut for offending the producer. To keep things moving, Sauer sidesteps entire swathes of evolutionary psychology—often with a dismissive wave at their alleged chauvinism. Fair enough, some of that literature deserves the side-eye. But still: if you’re going to rewrite the history of morality, maybe don’t ghost half the field.

Frankly, I would have loved to see this as a five-volume series—something truly unwieldy, excessive, and glorious. Sauer clearly has the range, and his ability to move from ancient kinship norms to WEIRD guilt complexes to the performative semantics of Twitter activism makes you wish he had let the thing breathe more. He’s brilliant, but sometimes a little too eager to make the next clever point before the last one has fully sunk in.

By the end, Sauer has given us something both expansive and intimate: a world history of morality that doubles as a skeptical self-help book for confused moralists. The Invention of Good and Evil doesn’t tell you what to believe, but it does offer a clear-eyed map of how we came to believe anything at all. It’s not preachy. It’s not self-satisfied. It’s more like being invited to a very elegant dinner party where the host hands you a glass of wine and whispers, “None of this makes any sense, but let’s toast to it anyway.”

Just don’t expect to walk away feeling morally superior—or even morally intact. Sauer’s final gift is a kind of gracious deflation: a reminder that our deepest convictions, noblest institutions, and most pious hashtag campaigns are all part of a long, improvisational experiment in not murdering each other.