A Latter-day Saint Ethic of Resistance to Christian Nationalism

Three specific ways to defend a diverse and pluralistic vision of American life

[Read the first half of Kyle’s essay here]

I would like to propose three suggestions for Latter-day Saint resistance to Christian nationalism. Behind these suggestions is the conviction that reappraising our view of American history is vital resistance for our practice of politics.

Moving beyond our persecution complex

In a recent conversation I had with Victoria Barnett, former director of the Program on Ethics, Religion, and the Holocaust (PERH) at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, she spoke of a meeting she had some twenty-plus years ago with senior LDS church leadership who were interested in pursuing a joint project with their office due to the heritage of persecution that Mormons and Jews share. McKay Coppins captured another indicator of our perceived persecution as a people when he reported that the late M. Russell Ballard had approached Mitt Romney to establish the Mormon equivalent of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) to defend church members in the public square, a proposal that Coppins reports Romney didn’t think was necessary.1 According to Romney, solutions to contemporary problems facing Mormonism will be likely found by looking internally, rather than externally: “In other words, we have met the enemy, and it was us.”2

Yet Coppins’s biography reintroduced the question of a Mormon civil rights organization. In this context, the editorial board of Public Square Magazine recently issued a statement calling for Latter-day Saints to form a public advocacy group akin to the NAACP or ADL. Determining the Latter-day Saint public interest as a collective entity, however, leads to the problem of policing who and what is normatively Mormon. This problem is inherent to any identity-based advocacy group; the ADL’s pro-Israel advocacy, for instance, targets anti-occupation Jews precisely because they challenge whether support for Israel is essential to being Jewish. An equivalent to the question of support for Israel might be opposition to same-sex marriage. Would a Latter-day Saint advocacy group make up for the lack of musket fire coming from the ivory tower at BYU? How and by whom are Mormons misunderstood? By each other? Or better, is a Latter-day Saint more likely to be the plaintiff or defendant in a religious discrimination lawsuit?3 Recognizing that we too often misunderstand and mistreat our fellow church members and our non-LDS neighbors alike will hopefully reorient the desire of some Latter-day Saints to join the dubious table of identity-based civil rights organizations towards more productive endeavors that center our agency, rather than our persecution.

Patrick Mason’s invitation for Latter-day Saints to exit the quaint walls of the “fortress church” is more instructive moving forward than older models that center persecution and mistreatment. We ought moreover to put into practice what Elder Patrick Kearon says aptly about the future of Latter-day Saint civic engagement: “Society is not something that just happens to us; it is something we help shape.”4

Confronting the challenges of the 21st Century—including Christian nationalism— demands that we step outside the fortress walls and take responsibility for the world around us. While Latter-day Saints are reportedly the least-favorably viewed religious group in the United States, efforts to improve our reputation should focus upon amending our role in the rise of the religious right, rather than pitying our persecuted history. Mormon Women for Ethical Government, for instance, is a trailblazing model for Latter-day Saint civic engagement that looks outward in its priorities, rather than inward. Additionally, conflating our past persecution with what Jews and others have endured throughout the centuries reinforces an ugly sense of Mormon self-importance in a post-Holocaust, post-Middle Passage world. Especially given that Latter-day Saints weren’t persecuted in Nazi Germany, along with the pre-war efforts of J. Reuben Clark and local ecclesiastical leaders to accommodate Nazism in line with most German churches, we ought to take responsibility in a spirit of repentance for historical wounds we’ve inflicted.5 Consider the well-documented antagonism of senior church leadership to the civil rights movement during the 1960s, for instance, or J. Reuben Clark’s lifelong enthusiasm for the fabricated Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a notorious antisemitic document that Clark was known to circulate among peers as late as 1958.6 Rather than apologetically defending or dismissing such examples, we ought to recognize how the problematic beliefs of Skousen, Clark, Benson, and others has shaped our modern church and to make amends where possible.

Seeking racial justice and countering antisemitic, anti-Muslim, and other forms of bias is vital to opposing the nativist, white supremacist attitudes that Christian nationalists thinly veil in their view of who and what qualifies as American.7 Our privilege and burden as Latter-day Saints is to take covenantal responsibility in the quest to shape a better society, rather than merely depending upon a future eschatological reality (i.e. the Second Coming) to undo all that is terrible in the world in the twinkling of an eye, as if God stands before existence like a hand hovering over a lightswitch, deliberating when precisely he should turn on the lights and end all suffering. That doesn’t sound like the loving God who weeps helplessly in Enoch’s apocalypse over a world that our agency actively (mis)shapes.8

Challenging American exceptionalism

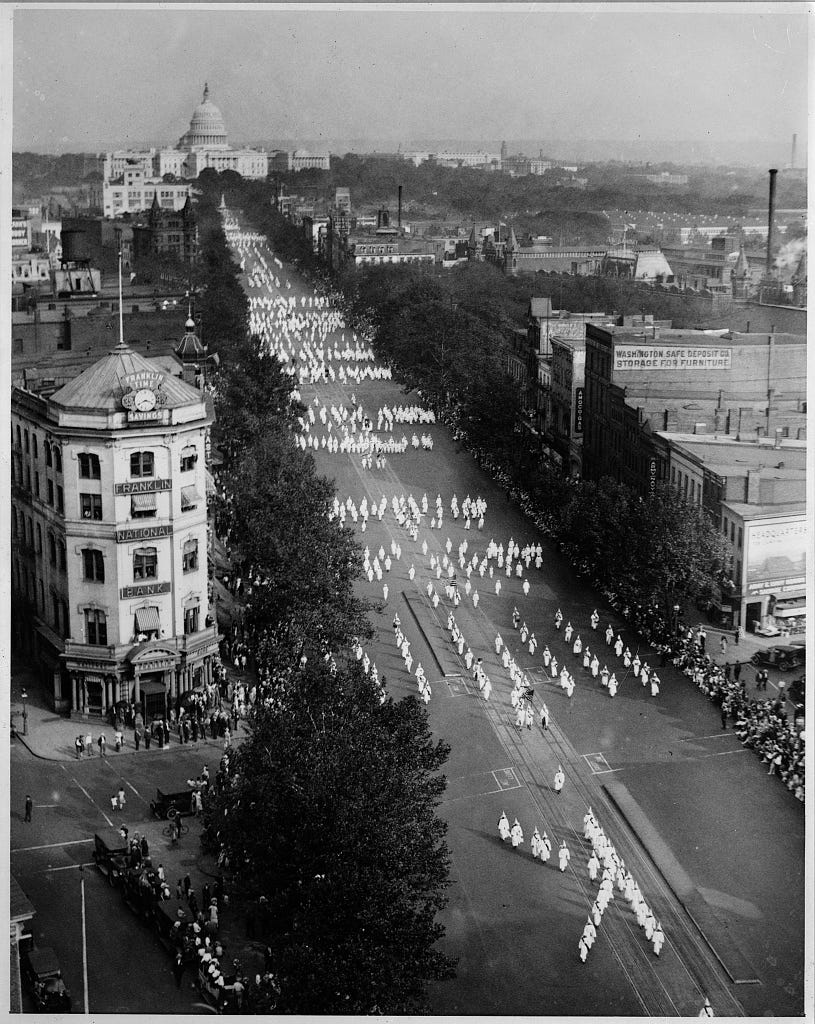

President Dallin H. Oaks’s reaffirmation of the ‘divinely inspired’ nature of the United States Constitution during the April 2021 General Conference was likely a roundabout rebuke of the January 6 insurrection, the greatest feat of white-supremacist Christian nationalism since the KKK’s 1926 rally in Washington, D.C. Given that the notorious insurrection on January 6 included a rogue Captain Moroni and others, a statement—however cryptic—about the peaceful transfer of power was necessary from senior church leadership. Yet by doubling-down on American exceptionalism, President Oaks risks reinforcing among church membership the Christian nationalist belief that God works through American history and in advance of American interests for divine purposes. If one couples this point-of-view with a whitewashing of the sins of American history, the result is a deeply problematic understanding of our nation’s past and future that reinforces the basic guiding tenets of white Christian nationalism.

Writing at the end of World War II, American public theologian Reinhold Niebuhr observed,

It so happens that the combined power of the British Empire and the United States is at present greater than any other power. It is also true that the political ideals that are woven into the texture of their history are less compatible with international justice than any other previous power of history.9

Niebuhr’s observation that British and American history and politics are “incompatible with international justice” confronts forcefully an entrenched history of imperial violence and racism and severely challenges the moral prerogative of the United States and Great Britain as divinely-inspired superpowers. While Nazi crimes were heinous and in many respects unprecedented in scope and devastation, they were not committed in a vacuum. Rather, imperialism, segregation, nativism, nationalism, racial pseudoscience, and Christian antisemitism all reached new heights in Nazi war crimes. Yet these sins are a common heritage of western civilization and remain a pregnant possibility. Right-wing Christian nationalism represents a concerted effort to deny the complicity of Christianity, the West, and the United States in perpetrating these crimes. Our resistance thus requires that we admit to American and Latter-day Saint sins of history if we are to advance a more just future. Given that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for much of its history cast itself among the sinners promoting racist, white supremacist attitudes, policies, and legislation, we have plenty of reason ourselves to repent and consider our ways, to echo the prophet Haggai (President Russell M. Nelson’s conciliatory work with the NAACP is a promising start).10

An honest encounter with American history compromises our pretension to divine favor as a nation. As Philip Gorski argues, divine covenant places a nation under judgment and myths of exceptionalism mark a dangerous form of collective pride that invites God’s wrath.11 Warnings against pride, materialism, and strife in the Book of Mormon thus become vital to countering the contentions that fuel Christian nationalism. While latter-day scripture is replete with references to a vaguely-defined American “promised land” blossoming in the latter days and elsewhere speaks of God “establishing” the constitution,12 the scriptural posture of prophetic critique resists abuse of its language as the basis for national pride and superiority. Prophetic critique holds thrones, dominions, principalities, institutions, and power brokers accountable. With God’s promises comes God’s judgment. We all know what happened to the Nephites, after all.

God within and beyond history

Latter-day Saints are inclined to believe that God actively intervenes in human history. Divine immanence, understood as God working through human actors large and small, is essential to a genuinely Mormon philosophy of history. God’s radical invasion into history is thus the basis for a divine providence in which the Kierkegaardian “infinite qualitative distinction” between God and man is wholly erased.13 We may thank Terryl Givens for applying David Bentley Hart’s assertion that “history has been invaded by God in Christ in such a way that nothing can stay as it was” to Joseph Smith’s Restoration.14 Yet this extension must be taken with precaution. To turn God’s incarnational invasion of history in the person of Christ into a dispensational pattern of recurring divine intervention is to resignify contingent human histories with divine orchestration. Given that religious nationalisms heavily build upon the belief that God actively works through human history by way of nations, constitutions, and wars, we ought to take our theological claims about history and providence more critically.

This is not say that God does not intervene into historical and human affairs: Mormonism avowedly rejects a Calvinist commitment to the inviolable transcendence and sovereignty of God, the sort of theology that led Karl Barth in Germany during the tumultuous 1920s and 30s to declare God ultimately unknowable to human beings and utterly beyond and above human history, which necessitated the Word becoming flesh and dwelling among us in the person of Christ.15 Our challenge as Latter-day Saints is to believe in a God that is at once within and beyond history, intervening in and through human history without providentially endorsing any national history or myth of origin. Resisting Christian nationalist claims that God works affirmatively in American history depends upon our holding these two contradictions together, an act of epistemic humility that should discourage us from making sweeping, romantic claims about the past and future of our nation or anything else merely historical and this-worldly. That “God is no respecter of persons” casts doubt upon Christian nationalist claims that America occupies a special place in God’s eye.16

Conclusion

My proposed ethic of resistance to Christian nationalism provides a theological backbone to concrete forms of political engagement that challenge the claims of right-wing Mormonism. White Christian nationalism à la Senator Mike Lee’s call to mobilize Catholics, Evangelicals, and Latter-day Saints behind the false messiah of Donald Trump deeply misunderstands the Christian Gospel. In a fallen world that only God can redeem, politics is merely improvisation and nations—including the United States of America—are the accidents of history. White Christian nationalism thus belongs to a flawed Weltanschauung that assigns to providence what only sin can pretend to possess: to speak in God’s behalf to justify oneself.

We have established that past Latter-day Saints have significantly contributed to contemporary American Christian nationalism and the rise of the Christian right. I anticipate that many readers may be critical of right-wing Christian nationalist politics, yet receptive to—and perhaps even defensive of—a received Latter-day Saint rhetoric of American exceptionalism. My ambition is to encourage us to rethink how we talk about American history and destiny as Latter-day Saints. Again, with God’s promise comes God’s judgment. If we are seriously committed to challenging Christian nationalism and MAGA-style politics, we need to do the critical historical and theological work of remembering that all of God’s promises are conditional. The Nephites were not up to the task, ultimately falling to the sins of pride and national self-importance. Yet if we are up to the task, we may learn from their mistakes and do the important work of repair in defense of a diverse and pluralistic vision of American life in the twenty-first century, one in which all of God’s children are treated with dignity and white Christian nationalism has no place.

McKay Coppins, Romney: A Reckoning (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2023), 192.

Coppins, 192. Quoted also in David Noyce, “What Mitt Romney sees as the greatest threats to the LDS Church,” Salt Lake Tribune, 21 October 2023. https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2023/10/21/what-mitt-romney-sees-greatest/.

While it is not an empirical, peer-reviewed study, Jeff Breinholt’s 2009 analysis of religious discrimination suits involving Adventists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Latter-day Saints poses an important question about where our priorities in the public square should be: https://www.mormonmatters.org/the-surprising-truth-about-mormon-employment-discrimination/.

Patrick Kearon, “Of Rights and Responsibilities: The Social Ecosystem of Religious Freedom,” Religious Freedom Annual Review at Brigham Young University, June 20, 2019, https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/article/transcript-elder-kearon-religious-freedom-byu-2019. Quoted in Patrick Mason, Restoration: God’s Call to the 21st Century World (Meridian: Faith Matters Publishing, 2020), 5–6.

For further reading on Mormonism and Nazi Germany, see David Conley Nelson, Moroni and the Swastika: Mormons in Nazi Germany (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015).

Douglas J. Tobler, “The Jews, the Mormons, and the Holocaust,” Journal of Mormon History 18, no. 1 (Spring 1992), 70. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23286361.

See Report on Christian Nationalism after the January 6 Insurrection, 1–3.

See Moses 7:28–34.

Reinhold Niebuhr, “Anglo-Saxon Destiny and Responsibility,” in God’s New Israel: Religious Interpretations of American History, ed. Conrad Cherry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 297.

See Haggai 1:5–7 (KJV).

Philip Gorski, American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), 125, 8.

For instance, see 2 Nephi 10:10–12; Doctrine and Covenants 98:4-7, 101:77–80.

Karl Barth, The Epistle to the Romans (London: Oxford University Press, 1933), 10.

David Bentley Hart, The New Testament: A Translation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), xxiii–xxiv. Quoted in Fiona and Terryl Givens, All Things New: Rethinking Sin, Salvation, and Everything in Between (Meridian: Faith Matters Publishing, 2020), 11.

See Barth, Romans, 28.

Acts 10:34 (KJV).

Very clear and candid writing. Thanks. This is what is coming and you are feeling it:

Our privilege and burden as Latter-day Saints is to take covenantal responsibility in the quest to shape a better society, rather than merely depending upon a future eschatological reality (i.e. the Second Coming) to undo all that is terrible in the world in the twinkling of an eye, as if God stands before existence like a hand hovering over a lightswitch, deliberating when precisely he should turn on the lights and end all suffering.

Zion is a social-economic-political project (again) in the 21st century that invites people of good will to contest the common good with loving respect for their rivals. The LDS are (as you note) going to do this internally before they can revolutionize the world like Joseph Smith aimed to do. Zion is bigger than the church, bigger than mortality—it is the program to heal heaven of wars with sacrificial love.

Amen, Randall. Thanks for sharing your thoughts. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as with many things, seems to occupy the beautiful center that needs to "hold": we are pre-millennial in the sense that Christ ushers in the Millennium and post-millennial in the sense that we are called to build Christ's Zion now. And by our understanding of the idea of religious freedom - its borders are to enlarge and by default - and things I hear from the tops of the mountains, seem to include as we go, believers of so many varieties.