Creatio Ex (Masonic?) Materia

A Review of "Method Infinite: Freemasonry and the Mormon Restoration"

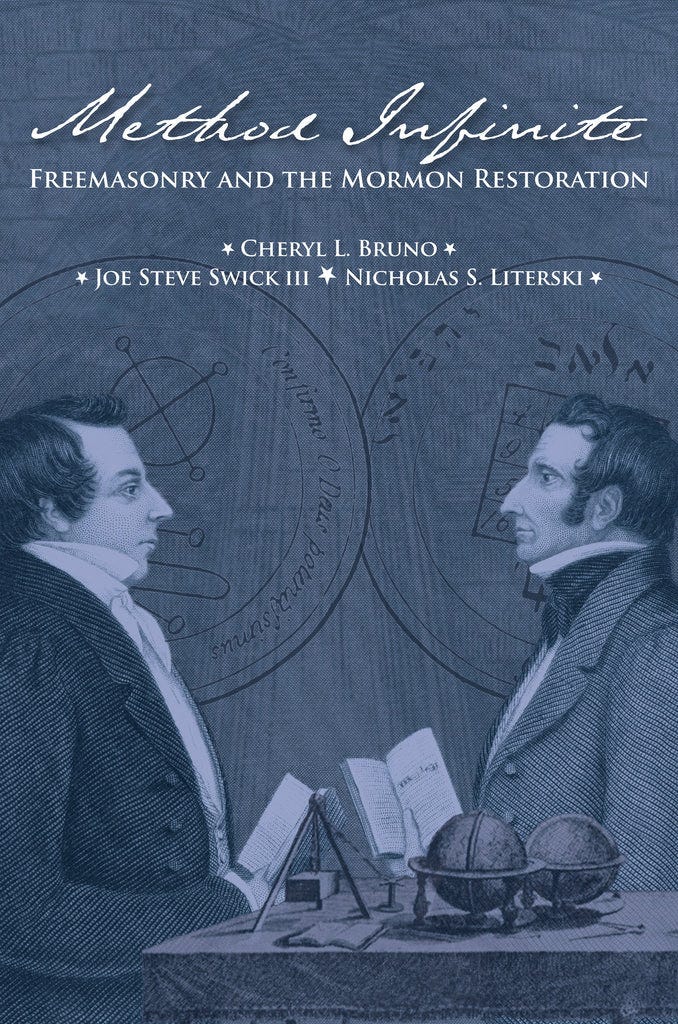

What hath Masonry to do with Mormonism? Darn near everything, according to the trio of authors behind Method Infinite: Freemasonry and the Mormon Restoration.

Many of us have probably at least heard in passing of the connection between Masonry and Mormon temple ritual. And most of us probably shrug our shoulders and avoid thinking too hard about it, partly because the thought of temple ritual being pilfered from somewhere else is discomfiting, but also because of the mysterious aura that shrouds Masonry—a shadowy fraternity that boasted as initiates such luminaries as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Harry Houdini, and Winston Churchill. Is it the Illuminati? Who knows.

When it comes to assessing the relationship between Masonry and Mormonism, people generally fall into one of four camps:

Masonry explains Mormonism through and through.

Joseph Smith prophetically fashioned some Masonic material for unique purposes.

Masonry is a corrupted form of an originally revealed system that Mormonism restored.1

Mormonism has nothing to do with Masonry.

Camps 1 and 4 are typical cases of reductionist and fundamentalist tendencies that have more to do with ideologically driven cognitive patterns than reality. The usual pitfall of any discussion of this subject is an utter lack of detail. Rather than drawing upon evidence to corroborate their position, participants in these conversations are too often driven by a sort of intestinal pathos that has no need for such trivial things as proof. This book, then, is a welcome entrant to the arena with its superabundance of details, down to the minutiae.

In the broadest terms, this book claims that the structural and ritual underpinnings of Mormonism are, in essence, the result of Masonic materials passing through Joseph Smith’s prophetic imagination—that Joseph Smith is best understood as a “Masonic restorer” who, rather than engaging in “mere slavish borrowing,” sought to “transform and elevate Masonic ritual into ordinances holding divine, salvific power.” Masonry, then, should be more properly viewed as the “spiritual handmaiden” of Mormonism. This is not an entirely original claim, but most prior treatments focus on the more obvious temple ritual connection. The originality of this book lies in making the case that, panning out to the wider view, the connections are both earlier and more extensive than heretofore imagined. For Bruno, Swick, and Literski, Masonry informed the development of Mormonism at nearly every point.

Each chapter covers a theme that the authors deem Masonically inspired, including but not limited to: the First Vision, the finding and contents of the Book of Mormon, the Book of Abraham, the construction of the Kirtland Temple and its rituals, the Danites, theocratic aspirations, the construction of the Nauvoo Temple and its ritual, the Relief Society, the King Follett sermon, and even the martyrdom of Joseph Smith.

On a certain level, the conclusion is inevitable. Joseph Smith was a Mason, consorted with Masons, built Masonic lodges, made the Masonic sign of distress while being murdered by Freemasons—it was Masonry all the way down. Sort of.

Some of the chapters are stronger than others, such as the insightful discussion in Chapter 16 of the King Follet sermon which, by the authors’ account, “represented the apex of Masonic experience,” as a “theological expansion of the concept of ‘progression up the line of officers’ in a lodge.” Chapter 17, detailing the possible parallels between the deaths of Hiram Abiff2 and Joseph Smith, passes so far into the Jungian realm of archetypes that it defies assessment, but I nonetheless enjoyed it (one of the authors, Nicholas Literski, has a background in depth psychology and it shows here). Chapter 6, “Mormonism’s Masonic Midrash,” on the other hand, is overly ambitious and falls flat in its attempt to articulate a theory of scriptural production.

Througohout this book, the reader will find a slew of fascinating anecdotes and insights, such as, but not at all limited to, the following:

The Relief Society was organized in Masonic fashion at a Masonic hall on the day after Joseph Smith became a Master Mason.

Orson Pratt baptized William Morgan’s3 widow, after which the patriarch Joseph Smith Sr. pronounced that she would meet William Morgan in the Celestial Kingdom. He was also among the very first baptized vicariously in 1841.

Brigham Young wore a Masonic pin, used Masonic references in his speeches, and used the Royal Arch cipher in his journal.

Thirty-three out of the thirty-six men who received their endowment from Joseph Smith were documented Masons.

Masonic elements of the Mormon endowment were intentionally effaced under the direction of President Heber J. Grant after a 1921 exposé.

Though admirable for its studious attention to detail, this book is not without its weaknesses. For one, the authors make no attempt to taxonomize the sources they employ, for either Masonic or Mormon materials. For instance, they don’t tell us to consider that Wife No.19 was an anti-Mormon book published in 1876 decades after the events it reports. Instead, they simply quote it as a source. That not all sources are created equal is a fundamental tenet of historical-critical scholarship, but it is not one which the authors consistently honor. Second, the book makes no attempt to contextualize Masonic influences relative to other possible sources of inspiration (see, for example, p. 275 of this review for what that might look like). Masonry was in the air, sure, but so was the Bible, Jacksonian democracy, a spirit of theological innovation, and what Richard Bushman has termed the “culture of boundlessness” which prevailed in the early Republic. Third, the book tends to discuss similarities without discussing differences. Fourth, at times the book seems to try to pass off indiscriminate amassing of details as a substitute for coherent argument, falling into an inchoate parallelomania.

For a non-specialist reader, then, this book may seem more convincing that it actually is. To be clear, the book is convincing on many accounts, just not all. That being said, the more judicious researcher has much to gain from trailing behind the authors’ vigorous plow. Lastly, the authors should be commended for their tactful and respectful handling of both Mormon and Masonic materials.

The lingering impression (and by far the most intriguing one) I had after finishing this book was that from the cradle to the grave, Joseph Smith was acting out one long Masonic legend, animated and possessed by the ghost of Hiram Abiff, following the dictates of an unconscious archetype. This was the authors’ subtle but persistent point, and perhaps the intended gestalt. Of course, this particular argument extends far beyond the (boring) pale of verification or falsification, but I sympathize with this type of gesture towards a universe filled with interwoven significance rather than devoid of it.4 Joseph Smith himself certainly inclined that way.

In the end, I can agree with the authors that when it comes to Mormonism, “Freemasonry was not the only ingredient that went into the mix, but it was a vital one.”

Early Church leaders often adopted this stance, such as Heber C. Kimball: “We have the true Masonry. The Masonry of today is received from apostasy, which took place in the days of Solomon and David. They have now and then a thing that is correct, but we have the real thing” (250).

The central character of an allegory presented to all candidates during the third degree in Freemasonry.

“The Morgan Affair” was a major event in 1826 involving William Morgan who, himself a Freemason but having become disgruntled with it, threatened to publish Masonic secrets. He was arrested and soon thereafter mysteriously vanished, presumed to be murdered. This gave rise to mass anti-Masonic sentiment in America that the organization never fully recovered from.

Along these lines, see also Edgar C. Snow, “One Face of the Hero: In Search of the Mythological Joseph Smith.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 27, no. 3 (October 1, 1994): 233–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/45225967.

A great resource on Masonic rites and the temples of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the podcast, "Church History Matters,' by Casey Griffiths and Scott Woodward in their series on the temple. It can be found at the Scripture Central website.

Thanks for this critical and positive review of an enthralling account of LDS and Masonic mutual influences in the early church history.