Best guess, I bought it somewhere before the intersection of UT-State Road 12 and US Highway 89, putting me near Panguitch, Utah. I was returning home from a weekend trip to Bryce Canyon National Park with some friends from college. Our group pulled over at a roadside rock shop, primarily to use the restroom, but also to break up our drive and stretch our legs. After hiking among the famed hoodoo towers of Bryce Canyon, the assortment of dusty shelves and tables splayed with bits of stone, crystal, and other trinket-sized lumps of rock and gem seemed a decidedly less impressive landscape than the one we had just left.

I paused at a small-corner shelf marked with a hand-written sign labeled “Petrified Wood” and examined some of the pieces for sale.

For $175, a throne-like trunk of stone, almost a foot-and-a-half in diameter, a near-transparent amber color splashed brilliantly across its cross section, yet still impressively barky along its perimeter.

For $45, a blue-red speckled gemstone of a wood-knot, polished and cut into a nearly spherical shape.

For $7, a dull-brown, bookend-shaped stump.

—

Wood petrification is, in a word, a drowning. It occurs when wood becomes buried underground and then is surrounded—drowned—in a kind of half-water, or the water saturated sediments of deltas, floodplains, or muddy ash beds formed in the wake of volcanic eruptions, floods, etc. In these settings, wood or other organic matter drowns in something not altogether liquid but in a somewhat-solid, semi-aqueous substrate of opposing origins, both fiery and watery.

Calling petrification a drowning is not (solely) for the drama of the word. A geologist would likely call the deprivation of oxygen from the environment the first prerequisite for petrification. Asphyxiation would do. Suffocation too. A non-oxygen environment ensures that wood’s core cellular tissues—cellulose and lignin—escape decomposition at the hands of fungi and bacteria. In this thick and watery, nonporous mud of ash, silica, and other minerals, bacteria and fungi are denied entry, barred from weaving what Jane Hutton calls the “lossy threads”1 of mycelium which generate, in the words of Merlin Sheldrake, “highways” upon which bacteria travel in order to digest decaying wood fibers.2 These ribbon-like roads created by fungi are absent in petrification, a process that, by the terms and conditions of geology, forecloses the opportunity for new life to emerge from eating the dead.

When microorganisms and fungal bacteria decompose fallen wood, mycelial enzymes bore holes deep into the wood’s cells, consuming the cellulose and lignin inside. This leaves behind space for fruiting bodies like mushrooms to grow, or spaces where fallen bits of spongy or crumbly rot-matter fall are consumed by insects. To put it simply, bacteria and other decomposing critters make room. They form the nooks and crannies, the valleys and peaks of the microscopic landscapes of decomposing matter. Within these new spaces, fungal life takes up residence.

But when silica and minerals petrify wood, silica floods the wood’s cells, replacing cellulose and lignin with minerals and metals that, with pressure and time, leave behind a stony replica of the tree’s formerly woody tissues. Where decomposition makes room for new ecological tenants, petrification floods that room with a deluge of mud.

From the standpoint of geological science, the sites, circumstances, and participants of these two processes seem wholly oppositional, even mutually exclusive. A decomposing or decomposed tree brings forth a multiplicity of new organismal lives from its death thanks to the agencies of other biotic beings. These are the lives and acts of fungi, whose mycelia pass nutrients around and across tree root-systems, as well as the lives of insects, bacteria, and others living within the soil. Yet with petrification, a fallen tree becomes subject to the influence of nonliving materials generally excluded from the category of living or biotic. The agents of petrification—the amalgamized sludge of mud, ash, and silt—transform the formerly organismal life of wood into a mineral, and distinctly non-living form.

What then are the lives of these newly non-living forms? How do these forms live outside the parameters of biotic or organic life? By virtue of simply existing, are minerals-made-from-organisms markable as beings? Does existence alone grant a life to substances like petrified wood?

—

Small, about 4 inches tall, somewhat pyramidal. A glossy, loam-colored veneer of the crosscut exposes the arcs of now-obsolete growth rings, while the backside of the slab retains a suggestion of bark. What might at one time have been the bright, vibrantly yellow, or whitish shade of the grain has dulled. Faint, almost smeared veins of a greyish off-white hue offer the last hints of the place where growth rings once rippled through the wood.

It comes to a not-altogether sharp point near its top, its edges nearly delicate enough to chip off with a flick of a finger. Its base is not quite level either; to jostle it would cause a gentle wobble to the left.

I usually keep this $7 stump of petrified wood on a side table near my front door, since decoration was likely the intended design of whoever cut, shaped, and polished it. I’ve taken to moving it around, setting it in front of me at my desk while I work, sometimes lying it flat on its polished face so that the barky side faces up instead of its intended-for-display surface.

I don’t know why I do this.

And for all my description, I’m not sure I can actually know the slab.

I don’t know who or what unearthed this piece of petrified wood. I don’t know how it came to be in the rock shop the day I returned from Bryce Canyon. I don’t know whether or how a swell of groundwater eroded the surrounding sediment and exposed the slab to the surface world allowing the human who found it to clean, cut, and polish it into its current form. I don’t know of its age, or of the space and time the slab occupied before it arrived in front of my eyes, along with its other $7-placarded fellows.

Of anything I could hesitatingly say that I know, there is this only this: apprehending this wood-rock seems to have activated an internal recognition of a liveliness within thing itself, a thing whose name I’ve given it so far—“slab”—suggests it to be clumsy and flat, frozen and immobile, utterly non-actant.

At times I imagine the slab as an ancient tree’s tooth, a slight concave divot near the base recalling the place where gum meets enamel. Perhaps this is a similar space where, as a tree, the heartwood tissues met the drywood. I wonder too whether this divot marks the place where a knot in the wood once formed, like a cavity. Did the knot prove too crowded a space for the flood of silica-sludge to seep in and substitute itself? Was it washed or chipped away during the time of its muddy entombment? Or was the knot (in an almost dental twist of fate) removed, smoothed by the human prospector, collector, or seller of the slab?

Here again my words expose a human hubris, the debilitating reduction of description, the losses incurred by language. The petrified wood is activated—is acting, is being—regardless of any feeble human awareness or turn of phrase I fling at the slab.

I wondered at first whether I canknow the slab. Now I wonder: should I seek to know it? If so, how?

—

Certain populations of petrified wood are protected from purchase thanks in large part to where they drowned, or rather, thanks to what these sites of drowning later became. I bought the small slab of petrified wood from a rock shop outside the borders of a US national park, Bryce Canyon. In these spaces outside the walls of a national park, purchase is permitted.

The Petrified Forest National Park in Northeast Arizona, however, guards one of the most highly concentrated deposits of petrified wood in the world. Throughout the Late Triassic period, trees that fell into the ancient river channels of the region were buried by silica-rich sediments. Wikipedia tells me that “most of the park’s petrified wood is from Araucarioxylon arizonicum, an extinct conifer tree.” Wikipedia goes on to say, as a point of interest, that “at least nine other species of fossil trees from the park have been identified.”

Then a rhetorical dagger: “All are extinct.”

Extinct . . . why should petrification assume or impose extinction? After all, the tree’s existence is not to my mind ended, just transferred into a nonliving form. Can a being be extinct if, though altered in form, it continues to be, if it retains its existence?

And crucially, what does a national park’s enshrinement of an “extinct” natural form within its namesake and ethos do to the life and story of the form itself?

—

As it turns out, establishing and enforcing borders around the linguistic, scientific, and cultural terms and conditions of extinction has been integral to the formation of many national parks throughout the United States. Often the threat of extinction for a certain ecological form or species prompts the creation of a park. In fact, many of these parks take up the name of charismatic natural forms—unique geographies, rare forest systems, or even a single outstanding plant or animal species—that the park aims to protect, shield, or conserve.

Redwood National Park.

Everglades National Park.

Sequoia National Park.

Joshua Tree National Park.

Saguaro National Park.

These natural forms become the namesakes of the park’s national form, the full-throated ethos of what the park proclaims to conserve for the enjoyment of all.

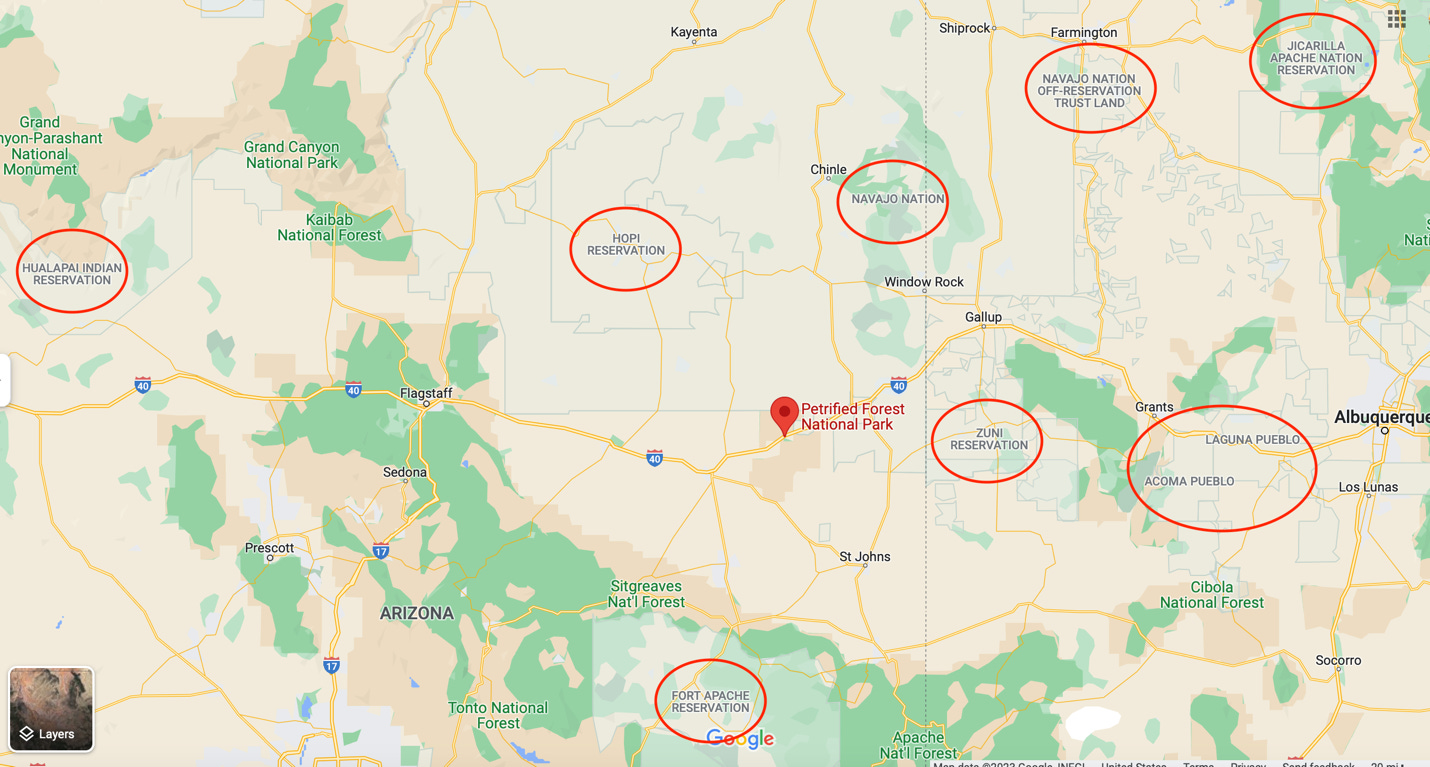

But threats and hints of another extinction hover above and seep within and around what many parks choose not to name, or else name only parenthetically. A cursory glance at the borderlines drawn around Petrified Forest National Park indicate the presence of the many displaced Indigenous peoples, whose lands were pushed to the periphery of a park-based, nationalized center.

William Cronon points out how a particular kind of extinction—the extinction of the mythological US frontier—both guided and continues to guide the violence of this border-making practice within national parks. The extinction of this foundational US myth lurks in the shadow cast by potential ecological extinctions which many national parks announce in their nomenclature. The extinction Cronon elucidates is, to me, the primary impetus for the expansion of the national park system in the twentienth century, and (I fear) a stronger motivation for the creation of parks than our government’s authentic concern that a species of flora or fauna may become extinct. “It is no accident,” writes Cronon, “that the movement to set aside national parks and wilderness areas began to gain real momentum at precisely the time that laments about the passing frontier reached their peak. To protect wilderness was in a very real sense to protect the nation's most sacred myth of origin,” a myth necessitating the displacement of the so-called wilderness’s original inhabitants.3

The case of the Petrified Forest National Park, as well of the wider history of national parks writ large, thus wrinkles to my attempts to know my piece of petrified wood. The specimens of petrification within the park are the fiercely guarded objects of extinction rather than the targets of possible extinction. They are watched over, praised, and preserved as the last remnants, the final remains, the entombed monuments to extinct species of trees. To know petrified wood in the way offered by a national park, I’m pushed to accept certain terms and conditions of extinction.

—

But there are odd interruptions to the park’s wielding of extinction, strange disruptions of the term itself, all of which emerge from and around petrified wood.

Beginning in about 1935, visitors of Petrified Forest have consistently removed several tons of petrified wood from the park each year. An estimated 12 tons in fact. Despite the present-day guard of National Park Service rangers, fences, warning signs, and the threat of a $325 fine, pieces of petrified wood have long been removed from the park borders.

While much of this wood never returns, some visitors send these pilfered pieces of petrified wood back by mail (sometimes years later), often accompanied by “conscience letters,” a term assigned by the park staff archiving the letters and returned pieces of wood. “Anti-theft messaging at Petrified Forest began early,” writes Gwenn Gallenstein, “evidenced by the park receiving 110 return letters between 1935 and 1980. Letters from the 1960s and 1970s mentioned that Petrified Forest had inspection stations at park exits where law enforcement personnel could ask visitors if they were leaving with petrified wood and check their vehicles . . . Individuals referenced being stopped at the stations and felt too embarrassed to admit to officers and their families that they had taken small pieces. The guilt weighed on their consciences until they finally returned the petrified wood, sometimes many years later.”4

These letters, according to Ryan Thompson and Phil Orr, “often include stories of misfortune attributed directly to their removal of the piece from the park: car troubles, cats with cancer, deaths of family members, etc. Some writers hope that by returning these stolen rocks, good fortune will return to their lives, while others simply apologize or ask forgiveness.”5

Reading these letters, my stomach lurches. Some of the letters cause me to chuckle bizarrely, but most of them cause me to twinge or wince at the many slings and arrows of conscience they describe. I wonder about the figures to whom these letter writers attribute their guilt, their misfortune, their need to make amends. The addressee of these letters is not fixed . . . yet it feels almost clear to me to whom these letter writers were compelled to apologize.

The park also petrifies.

—

Another conscience letter was written on the back of a postcard from Bryce Canyon. They name themselves “Anxious,” adding the parenthetical surname, “(not to get bad luck).”

It seems like the letter wants to remind me—and me specifically—that I too was near Bryce Canyon when I decided to take a piece of petrified wood for myself. Despite the different modes of taking, I, like “Anxious,” feel a squirm of something like conscience as I read.

What I assume is the author’s self-portrait is scrawled in the space set aside for writing the address of the card’s intended recipient.

The face stares, and I stare back.

—

Elizabeth Hardwick writes of things fossilized as “persons and places thick and encrusted with final shape.”6 But the shape of my slab of petrified wood, this tree fossil, is final only in that its physical proportions cannot now shift or grow in the ways it once could as a tree. Though its shape would only change through a clumsy act of smashing, breaking, or cracking on my part, the slab’s vibrancy—its undeniably actant materiality—ensures a constant concrescence of its story with mine.

Consider this then my own conscience letter, just not to Bryce Canyon National Park, not to Petrified Forest National Park, and not to the rock shop where I spent the $7.

“Dear Slab,”

Hutton, Jane. 2020. “Arresting Decay: Tropical Hardwood from Para, Brazil, to the High Line, 2009,” in Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements (New York: Routledge,), 188.

Sheldrake, Merlin. 2020. Entangled Life: How Fungi Make our Worlds, Change our Minds, & Shape our Futures (New York: Random House), 174.

Cronon, William. 1996. “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting back to the Wrong Nature.” Environmental History, 1(1), pp. 7-28, 13.

Gallenstein, G. M. 2021. “Remorseful Returns: What to Do With Returned Surface-Collected Items From National Park Service Units.” Collections, 17(1), 54-67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1550190620951533, 63.

Thompson, Ryan and Phil Orr. 2014. Bad Luck, Hot Rocks: Conscience Letters and Photographs from the Petrified Forest. Los Angeles, CA: Ryan Thompson and Phil Orr. https://archive.org/details/bad-luck-hot-rocks.

Hardwick, Elizabeth. 1976. Sleepless Nights. (New York: Random House), 5.