Separation of Church and Party: Part Two

Part two of a two part article exploring the historical, current, and global relationship between The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and politics.

Earlier this month, I wrote an article outlining a political history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the United States. I emphasized how the Church’s relationship with American politics affects the pol’ political leanings and beliefs today. Because Utah is home to the largest Church population in the United States and Church headquarters, it is uniquely saturated in Church culture. In part one, I showed how beliefs firmly held by some members are a reverberation of preaching politics over a pulpit— leaders blurring the lines of faith and personal politics to accomplish a goal, whether intentional or not. For an example, look no further than Senator Mike Lee, who recognized this phenomenon in many Church attending voters and used it for his “President Trump is like Captain Moroni” sermon. Identity politics, the assumption that a group of people shares similar values, experiences, etc., furthers the moralization of politics.

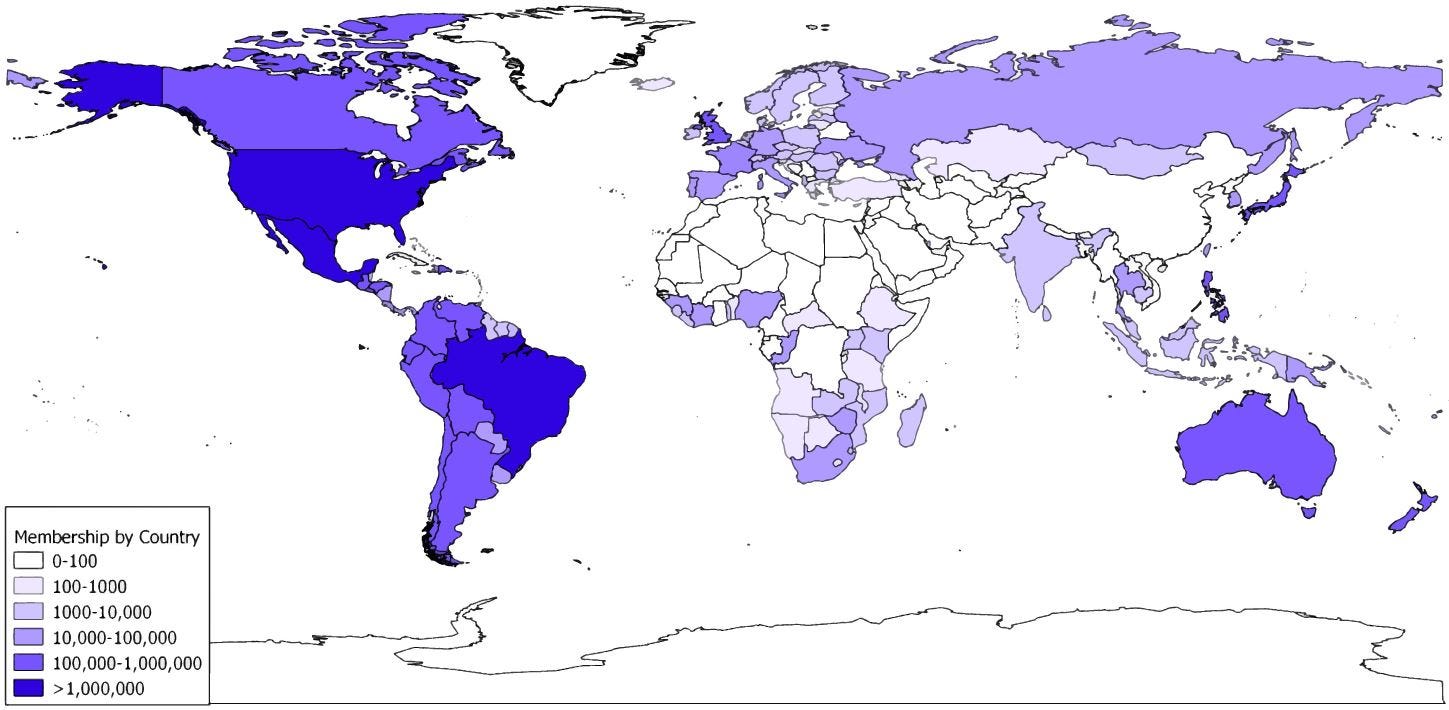

My objective is to neither condemn nor promote any political party, but rather to give a historical overview of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, identify where some beliefs or attitudes within the Church may have originated, remind readers that this is a global Church, and discuss what unity may look like in a Christ-centered organization. Although most of the membership of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints lives outside the United States, a supermajority of all U.S. members live in the Intermountain Region. Even globally, most Church members live in the Western Hemisphere. This has created some inadvertent bias Church leaders are working to correct, but they need members to help and to listen better.

When we treat our personal political philosophy as an opinion and not doctrine, we make room for people of varying backgrounds and ideologies who bring fresh and often inspired perspectives into quorums, classes, and presidencies. Indoctrination or compliance with institutional and cultural pressures is no longer used to measure piety. Those measurements and outcomes cease to matter because spiritual autonomy and revelation are honored instead. As opposed to consensus, when real unity is achieved, identity politics loses its edge, and Christ can govern our lives.

Part two will be more opinion than researched-based. Feel free to disagree. Also, feel free to write me an email or comment at the end. If it is sincere, I know I’ll be better for it. Thanks for reading.

Part Two: Present Day and Unity

The Need for Global Perspectives

After one of Elder Benson’s general conference addresses where he vehemently attacked Socialism and Communism, several leaders were upset. They expressed their concerns to President McKay, which was recorded in his biography:

“[The address] had taken on the stature of an official Church position without having been formally endorsed. McKay, who was consistently more concerned with the overall fight against Communism than with the tactics, deflected this concern: he “knew nothing wrong with Elder Benson’s talk, and thought it to be very good.” Brown pointed out one consequence for Church members of Benson’s broad-brush attack: “All the people in Scandinavia and other European countries are under Socialistic governments and are certainly not Communists. Brother Benson’s talk ties them together and makes them equally abominable. If this is true, our people in Europe who are living under a Socialist government are living out of harmony with the Church.”

It can be easy to forget when living in a nation that many herald as the “promised land,” that while The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was restored in the United States of America, it is not an American church. President McKay’s limited perspective, as illustrated in this account, is not unique. Many Church members in the United States, and especially in the Intermountain West, continue to make sweeping declarations of policy, belief, or opinion that only apply to their personal experiences, without recognizing that they are ostracizing other Church populations.

Currently, there are 50 dictatorships in the world. Like Cambodia or Venezuela, some of these countries have a pretense of democracy, while others are outright autocracies such as Saudi Arabia and North Korea. Ethnic politics, which Ethiopia has used to form four major political parties, are disastrous. Some countries, like India, have parties like the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that were created from religious nationalism. Most first-world countries, such as Brazil, Germany, England, Switzerland, France, have many political parties in their government. Only a few countries in the world, like the United States or Zimbabwe, have a two-party system. Therefore, assumptions based on American-style political systems are likely to be, at best, irrelevant to Saints in other countries.

A Path to Unity on the East Coast

David, who requested a name change to remain anonymous, grew up on the West Coast and learned early how to navigate relationships with those who didn’t always agree with his beliefs. In early grade school, his best friend told him about the Mountain Meadows massacre (he had read it in a book his parents gave him to inoculate him against any Mormon proselytizing attempts). David’s mother worked to create space for people of various faiths to pray in their local Church, despite pushback. He grew up with friends across the political spectrum. But when David and his young family moved to the East Coast for graduate studies and to work on Mitt Romney’s campaign, his skills were put into a refiner’s fire of sorts.

The East Coast ward David moved into was well known for its progressive culture and renowned intellectuals who are pillars in the community. Members were encouraged—expected even—to bring up and challenge difficult aspects of the Church in sacrament meetings and at Sunday school. These attitudes were meant to challenge the stereotypical Church culture to advocate for the disenfranchised or often forgotten in the Church. The ward culture was well-intentioned but could be intimidating.

On David’s first Sunday, he recalled being introduced as “David, a graduate student attending a local university and working on the Romney campaign.” While David said his personal political views are impossible to distill or summarize, working for the campaign put a stamp on him, watering down his principles and labeling him as a Republican. This created some interesting relationship dynamics between his conservative and liberal friends. He had to clarify his nuanced views on issues where it was assumed he would fall in line with the Republican Party. While there was never a direct confrontation with his ward members, David felt the need to reassure his new friends, “We can still be friends even if you don’t vote for Mitt.”

There were times David felt he needed to hide the more controversial facets of his political ideology from his friends (both Republican and Democrat) to maintain peace and avoid awkward confrontations. However, those who were able to disentangle their friendship from their politics were able to enjoy years of friendship that enriched David and his family’s lives. Those who were unable to quietly slipped away without much notice. It was open conversations that demonstrated tolerance and love despite political differences that forged such deep relationships.

Because of the transient makeup of the wards in the area, bishops living outside the ward boundaries were regularly assigned to the ward. David recalls that one Sunday in November 2015, a new bishop was called. The bishop came from an established family in the area that was well known for being conservative. It was a fast-and-testimony meeting, and the day the Church policy regarding the children of same-sex couples was leaked. Members got up and read parts of the document and expressed their frustration and painful emotions with the new policy. It had been a tense meeting when the new bishop stood up. David remembers the bishop validating the members’ feelings. He remembers him saying, “The Church is not perfect. This is a difficult, painful policy. We will work through this together.” Political lines were abandoned, ideologies were not brought up at the expense of another’s feelings. David felt the experience did more to establish an inspired, people-first leadership faster than perhaps any other experience could have.

Unity is ineffectual without a confrontation of ideological views. Living in echo chambers and associating with culturally congruent people stunts growth and makes unity a mere Potemkin village. On the other hand, listening to those who disagree with us with kindness, like David’s congregation and their new Bishop, creates opportunities for the Spirit to highlight truth together.

Perhaps sometimes confrontation is avoided, or doubt is suppressed because there is a fear of violating covenants. There is a tendency to lump any degree of criticism or disagreement with Church leadership in with “evil speaking of the Lord’s anointed,” fearing it’s better to avoid the appearance of evil than to take the time to analyze a leader’s decisions prayerfully. Is it okay to disagree with Church leadership on issues we feel strongly about? The answer depends on personal revelation. In reality, the Church encourages the members to view leaders as imperfect and is slowly working to acknowledge mistakes. This is not necessarily fault-finding or evil speaking of the Lord’s anointed. Instead, it is an opportunity to clarify personal spiritual purpose and direction, strengthening the relationship between ourselves and Christ and extending grace to leaders.

To take the 2015 Church policy as an example, isn’t mourning with those that mourn just as vital as speaking well of the Lord’s anointed? Why can’t we do both? We can respect the pain of our brothers and sisters who are hurt by decisions leaders make while also extending grace and trust to leaders whose jobs are unimaginably difficult. Above all, we can give space for personal revelation as it will take people in different directions. It’s important not to judge their actions as wicked just because they’re different.

Negotiating Cultural Differences in Hong Kong

When interviewing Stacilee Ford, an American expatriate, it became immediately apparent American politics do not correspond with the current political climate of Hong Kong. A professor at the University of Hong Kong, she says her class delves into deep discussions about the American election but may refrain from discussing certain Hong Kong leaders and issues. She and other teachers must navigate anxiety about how the recently-passed National Security Law impinges on academic freedom. Ford assumes that she and her students may be under surveillance as the Hong Kong Government aligns with Chinese Government leaders concerned about sedition in the wake of protests in the city over the past two years.

Open discussion of politics is not common among Church members. The historical legacy of British Colonialism in Hong Kong meets contemporary Chinese desires to overcome a “century of shame” returning to pre-colonial status in the region. Race and racism in Asia are both familiar and unfamiliar to Ford, who sees Church members quietly align along pro-protest or anti-protest lines.

Identity politics, however, are present with congregants manifesting complex and intersecting loyalties to sub-ethnic as well as racial identities. For example, members from Hong Kong, Taiwan, the PRC, or across the Chinese Diaspora may have differing views about various issues but are all able to claim a dominant Han Chinese privilege that is akin to America’s “white privilege.” Yet Caucasian Latter-day Saints still enjoy a certain amount of privilege as well.

A notable demographic in Hong Kong is the cohort of female domestic workers, mostly immigrants from the Philippines or Indonesia who leave their families and send wages home. These women make up ten percent of the city’s working population and have the largest economic impact in Hong Kong but are marginalized members of society with nominal support and harsh living conditions. On average, domestic workers cost a third of the price of tutors or daycares, allowing for increased socioeconomic mobility for expatriate and local Chinese households. Only 18 percent of domestic workers have bank accounts, which are difficult to attain when their only day off is Sunday when most banks are closed. Due to lack of education and desperate situations, 83 percent of these workers report being in debt, and many fall prey to financial scams.

Many members in Hong Kong are domestic workers, and several branches in the area are primarily composed of these women. Branches that consist mainly of these domestic workers are called “sister branches” and are around 97 percent female. Working to abandon identity politics and finding commonality between domestic workers, Chinese, and other expatriate members of the district has been a fulfilling and difficult challenge. Understanding how feminism manifests in Hong Kong and its differences from American feminism has also been a transformative experience for Stacilee.

It seems the key to understanding feminism and politics among domestic workers in Hong Kong, and perhaps other various parts of the world is taking time to identify the desires of the people. What excites them? What are they passionate about? Why are they voting a certain way? Why are they posting this on social media? Stacilee has witnessed the women in her sister branch express a range of political views but are more inclined to focus on more immediate material interests given the lack of time they have for socializing and self-care. They value domesticity, planning ornate meals and decorations for Relief Society activities. This was something that expanded her notion of feminism – formed mostly in the U.S. (particularly Boston and New York City), where domestic labor was seen as inhibiting rather than enabling empowerment.

Initially, she was concerned or critical of women in the sister branches who spent so much time preparing for events given their limited time and resources. As she observed and learned from members in the sister branches who patiently endured her queries, she discovered that this was an area where these women felt empowerment. Likewise, in her own branch, where women from various cultures chose to manifest self-determination in more “traditional” ways, Ford says she observed different types of feminism. Stacilee’s next steps were clear: move out of the way and support them.

In Decolonizing Mormonism, Stacilee wrote about a sister branch celebrating the heritage of the Church on their own terms without being tainted by American exceptionalism:

“Reenactments of nineteenth-century LDS Church history are common-place, including the Mormon pioneer trek along the North American frontier (complete with full-scale representations of handcarts, jagged cardboard rocks, and imitation snow squirting out of bubble guns). But the ingenious efforts to recreate the past in twenty-first century Hong-Kong is not celebrating Euro-American Mormon Manifest Destiny via tribute to “the builders of the nation,” the “blessed honored pioneer(s)” (of course, the narrative is a stretch, considering that Mormon pioneers were forced to flee beyond the legal and geographic borders of the nation). Domestic workers in Hong Kong reclaim and revise pioneer narratives to sustain hope for a better future in twenty-first century Asia. Although they parallel their nineteenth-century ancestors in their embrace of the notion of chosen-ness, the “promised land” is more figurative than other-worldly. Meanings are mobile and reflective of challenges that come by living between and beyond national borders.”

Women in a sister branch in Hong Kong took a cultural reenactment from American history that even I, as an American teenager who donned pantaloons and dragged a handcart for five miles in a hot Ohio July, struggled to connect with and made it their own. If they had tried to replicate a reenactment from my youth conference, perhaps they would have missed the most important and applicable themes to them.

What is Gospel Unity?

Before being willing to discuss unity within the Church, Stacilee felt it necessary to define it. In her experience, many in Hong Kong— both at Church and in society at large— have used the term unity to quell dissent. While this sort of pressure is muted at Church, it is currently generating widespread anxiety in Hong Kong society. For example, harmony is often the term used by Hong Kong and Beijing authorities to silence opponents, and the silencing can be enforced in various ways. The most dramatic examples of forced harmony reach beyond censorship to include the imprisonment (or worse) of protestors who refuse to “harmonize.” This is not unity.

In his book, Beyond Politics, Hugh Nibley said, “Let us make one thing clear: contention is not discussion, but the opposite; contention puts an end to all discussion as does war...In reality, a declaration of war is an announcement that the discussion is over.” Unity does not mean conforming or silencing. Unity does not mean asking those who disagree with policy to leave or shaming them for their choices until they leave on their own. Unity is decoupling friendships from voting records. Unity means not hiding controversial parts of a person to avoid arguments or end friendships with those who think differently. Unity means paying close enough attention to neighbors to identify what makes them feel empowered and then supporting them with sincere joy and love.

It should be mentioned that disagreement is a normal part of unity. Nibley said, “Satan was not cast out for disagreeing, but for attempting to resort to violence when he found himself outvoted.” Practicing confrontation without escalation and learning to thrive with others regardless of race, tribe, culture, politics, or beliefs will be uncomfortable because it is in direct contrast to identity politics, but it is essential. Those who wrestle to find God, whether in their own spiritual journey or finding God in others, will find unity.

L. Hollie McKee, a member of the Church from the U.K., explained:

“The kingdom of God was designed to be diverse and in so being, is a place of inclusivity, equality, and unity. Celestial levels of unity are attained, I believe, when we can demonstrate respect and openness to the beliefs of all God’s children, while feeling safety expressing our own personal values.”

I remember as a missionary, I often confused inviting others to come unto Christ with colonizing converts. Unity does require a degree of personal sacrifice and assimilation, but the only culture we are trying to appropriate is Christ’s. Elder Quentin Cook said, “Unity is enhanced when people are treated with dignity and respect, even though they are different in outward characteristics.” God governs us as we study and pray. While we will consecrate whatever is asked of us, unity does not necessarily require us to sacrifice our personalities, culture, political leanings, or personal revelation to fit a mold.

Transcending Earthly Politics

Although there are hundreds of governments and political parties in the world, God delineates the Kingdom of God from the laws of men. In other words, there are all governments in the world, and then there is God’s government. Hugh Nibley said, “The governments of men and their laws are completely different from those of God. We do not attempt to place the law of man on a parallel with the law of heaven.” Though some mortal politics seem better than others, all fall short of God’s laws.

As stated in the Articles of Faith, we believe that when Christ comes, He will establish the Kingdom of God. Our mortal politics are not going to save us; Christ is. This does not mean our politics are meaningless. They are important, but they are temporary. Christ will come, and every injustice will be made perfect in Him. Knowing there is a perfect system that has been promised encourages us to strive for the best policies while understanding imperfections and limitations. Belief in the Kingdom of God separates morality from politics. God’s law is doctrine and is perfect. The laws of men are not. When politics are identified as imperfect, Church and state can finally be decoupled. Nibley said, “The kingdom is beyond politics; specifically, it is beyond partisan party politics.”

Example of Politics and Policy in Zion

A pressing question that surfaces is, how do we unify so many different peoples and cultures when experience ranges so vastly? In her discourse, This is a Woman’s Church, Sharon Eubank highlights an experience of discussing policies that didn’t seem progressive to her but were to women in other parts of the world. Listening to the experiences of others puts issues in perspective and inspires us to work towards unity. At the beginning of each dispensation and when Christ was on the earth, Christ established His law and worked to unify those around Him. We can see evidence of this in the scriptures.

The Book of Mormon

Fourth Nephi 1:16 says:

“And there were no envyings, no strifes, nor tumults, nor whoredoms, nor lyings, nor murders, nor any manner of lasciviousness; and surely there could not be a happier people among all the people who had been created by the hand of God.”

Of this scripture and its governmental implications, Sharon Eubank said,

“As I studied that scripture, I started asking myself, what would it be like if there were no whoredoms? What would society be like? So here’s my list:

Teenage couples don’t get pregnant and have to get married to the wrong person.

Lives don’t get warped and stalled by sexual abuse.

There is no fear of rape or violence…

…There is no market for prostitutes.

There is no sex trade, or there is no sexual slavery.

Spouses don’t have affairs or commit adultery.

Marriages stay intact, and children aren’t raised in the insecurity and divided loyalty of divorce.

Cities don’t have seedy, creepy neighborhoods that are filled with adult theaters and deviant bookstores.

There is no appetite for pornography – it doesn’t degrade the people who make it or who watch it. It doesn’t warp the sexual development of young people and rot the relationship between a husband and a wife.

There are no children being raised by a generation of women and painfully wondering where their fathers are.

All of the energy and the money that goes into all of those activities above the above is available for something else.

How is that not more free and not more desirable for women, for men, for children, how is that not?”

I would add that when people are living in the Kingdom of God, issues that were once hotly contested are resolved. It isn’t that they were unimportant, but they are now reconciled.

The Beatitudes

In the Beatitudes, found in The Book of Mormon and The Bible, Christ exhorts both the people in the Americas and those in Israel to follow a code of conduct. Despite these people living thousands of miles away, worlds and cultures apart, the verses are identical. Where politics fail to unite us, charity and the policies of the Kingdom of God never fail in their own right. In every culture, there is a need for a peacemaker. In every state, province, or territory, there are people who extend mercy. In every language, the pure in heart are revered. Those that are poor in spirit, regardless of gender, race, tribe, or station, are willing to accept the Gospel of Jesus Christ and live in His kingdom.

Conclusion

The political schism that members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints face in America is not unique to our religion. We are at a crossroads; we must come together despite increasing differences. We must learn to listen, open our minds and hearts. We must learn to disagree with one another and still be at peace. If we fail to do this, discord and contention will reign, and discussion will be over.

One thing that came to mind as I wrote this article was Max Lucado's book, You Are Special. In the book, wooden dolls called Wemmicks live in a village and are obsessed with giving each other star or dot stickers based on their outward performance or projected identities. One Wemmick covered in dots named Punchinello visits his Maker and learns he is remarkable for who he is and not what he does. Upon this realization, his dots begin to fall off.

I desire to avoid making choices to appease a star or dot-studded Wemmick camp. I desire to make my own decisions because of the knowledge of who I am. When we know who we are, we see others for who they are and respect them. Cultural, racial, lifestyle, or partisan differences cease to be walls and instead become doors because Christ-like love wills it so. By listening to each other’s desires and needs, we can support one another-- even if it's different from what we would do or think.

Once we understand our identity as children of God, we can appreciate various opinions without needing to be accepted by or being a part of identity politics. Christ is the Great Equalizer— He who identifies with all persons by taking upon Himself their experiences, their pains, and their disenfranchisements. He invites anyone willing to be part of His group. The more we understand Christ’s politics, the more we can resist assigning morality to individuals because they are different. If we want the Gospel to “[penetrate] every continent, [visit] every clime, [sweep] every country, and [sound] in every ear,” then we must make space for them— even if they are Democrats.